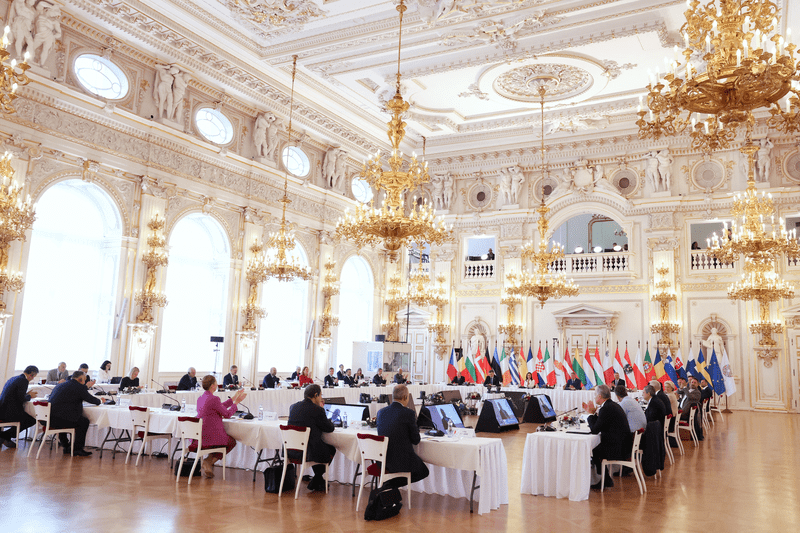

Friday’s informal meeting between all EU heads of state has failed to bring clarity on how—or indeed, whether—a cap on imported gas prices should be implemented. Within Prague’s royal castle walls, leaders did however commit to more financial and military support for Ukraine.

It was not a small irony that the EU’s latest summit on October 7th was held in Prague; protests against sanctions on Russia, which have in large part contributed to the present energy crunch, have been among the largest in that very capital.

With revolt in the air, speed is therefore of the essence, as surging energy costs (over 200% higher than at the start of September 2021) are wreaking havoc on European industry and populations while it threatens to plunge the bloc into recession—and all this with the cold sting of winter (predicted to be more acute than usual) yet to come.

Day-long talks between the EU’s 27 countries revealed that while most agree to such a cap—so that Europe will weather the next couple of years—a detailed approach has yet to be ironed out.

The bloc’s executive European Commission has therefore been tasked to come up with proposals until the European Council convenes on the 20-21st of October. Among the many options available to it is 1) a general cap on all gas, 2) a so-called “dynamic corridor” (which would prevent prices from going either too high or too low), 3) a price ceiling on gas used for power generation specifically or 4) one targeting Russian gas only.

Italy’s Mario Draghi—for now still acting caretaker prime minister until the formation of a new government under Brothers of Italy’s Giorgia Meloni—said the European Commission could potentially combine some of these, as it envisions a broader package of both short-term measures to lower prices and longer-term steps to reshape Europe’s electricity market.

The cap, then, is but one of many proposals the Commission could make to handle dwindling gas supplies from Russia (which formerly met 40% of Europe’s demand), and mounting prices. It is the most drastic one though, and the one with the heaviest drawback.

In a recent Euronews article, energy analyst Elisabetta Cornago for example warned that market intervention via such a price cap was “unchartered territory” for the EU, which had long held to a largely liberalized energy market that observed the rules of supply and demand.

Another analyst noted that such an intervention would “quickly start costing billions” because it would force governments to continually subsidize the difference between the real market price and the artificially capped price.

“If you are successful and prices are low and you still get gas, consumers will increase their demand: low price means high demand. Especially now that winter is coming,” said Bram Claeys, a senior advisor at the Regulatory Assistance Project. He added, “this increase in demand will push up prices again, putting pressure on your gas cap or your government budget. Again, there will be a risk of not getting enough gas.”

Additionally, Germany (the EU’s largest economy), the Netherlands, and Denmark have voiced concern that such a cap would make it difficult to buy the gas their economies need, as such a price limit on European imports alone would simply lead to gas being diverted to Asian countries.

On the summit’s sidelines, Germany’s Chancellor Olaf Scholz argued for a global buyers’ alliance instead. By linking up with other energy-starved countries in Asia, such as Japan and South Korea, big exporters could be convinced to lower costs.

Berlin’s latest foray into autonomy has rankled other nations, such as Poland, which views it as selfish. It lambasted Berlin over its plan to spend up to €200 billion in subsidies to cushion the blow for German consumers and businesses.

“The richest country, the most powerful EU country is trying to use this crisis to gain a competitive advantage for their businesses on the single market. This is not fair, this is not how the single market should work,” Polish PM Morawiecki said.

Scholz defended this course of action as the right thing to do, while reminding his counterpart that France, the Netherlands, and others had their own self-serving support measures in place as well.

Indeed, not all nations are as wealthy as these to finance such expenditures. French President Emmanuel Macron made note of this, as he suggested that member states could make use of a European fund that previously had provided loans for furloughs during the COVID-19 pandemic.

During a later press conference, the European Commission’s chief Ursula von der Leyen stressed the need for solidarity, but above all in energy matters, as she hammered home the crucial advantage joint gas procurement brings.

While Europe’s storages are now at 90%, at winter’s end these would be depleted, which makes it of “paramount importance that we have a joint procurement of gas so that we avoid outbidding each other …, that we have collective bargaining power,” she said.

While the energy crisis is sure to cause friction among EU member states for some time to come, on one point absolute unity reigned: Ukraine.

“We are determined to mobilize all possible tools and means to support Ukraine with financial means, with military support, with humanitarian support, and of course with political support,” said the European Council’s President, Charles Michel.

Von der Leyen reiterated the bloc’s commitment to the war-torn country for “as long as it takes,” after Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky had made his customary video address to the leaders present at the summit.

Again, the Ukrainian leader asked for more military hardware, such as air defense systems to protect Ukrainian energy infrastructure from Russian strikes, and for funds for Ukraine’s rebuilding.

The EU’s top diplomat, Josep Borrell, said he was in favor of meeting Zelensky’s requests, and advocated for more military support, which would include the training of soldiers. Starting from the Russian invasion of Ukraine in February to now, the EU has poured over €5.4 billion in macro-financial assistance into Ukraine, with an additional €2.5 billion going to military assistance.

Security, energy & prosperity must be closely interlinked, with energy becoming the most important geo-strategic issue

— Josep Borrell Fontelles (@JosepBorrellF) October 7, 2022

We will discuss these issues with EU leaders

I will also ask for their support to the 6th EPF tranche & Ukraine training mission#EUCOhttps://t.co/wPMMZEJksE pic.twitter.com/KIFATrrhhn