Benjamin Netanyahu said the world needs more leaders like the Hungarian prime minister, while Javier Milei said Viktor Orbán has made Hungary a bastion of the Western world in a Europe that is being engulfed by darkness.

The UK has reached an agreement with Rwanda for undocumented, single men arriving in Britain through the English Channel to be sent to the African state, where their asylum applications will be processed. In return, Rwanda will receive £120 million in development aid.

This comes after the House of Lords rejected key elements of Boris Johnson’s Nationality and Borders Bill concerning asylum and immigration, which, among other priorities, aimed to facilitate the revocation of British citizenship by the Home Office.

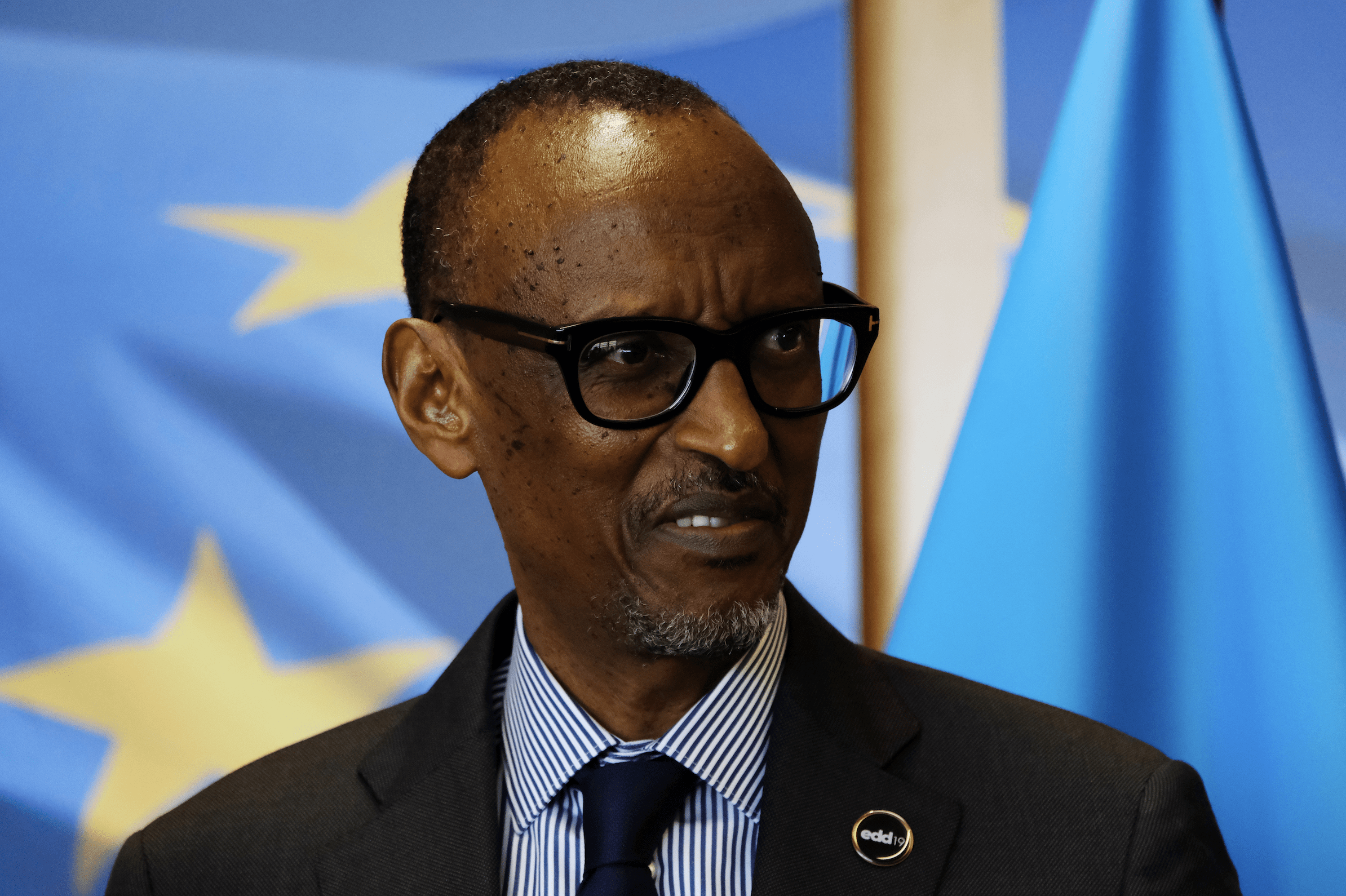

The deal with Rwanda was announced by Home Secretary Priti Patel on the 14th of April, who traveled to Kigali, the Rwandan capital, where she spoke of setting an important precedent:

Our world-leading migration and economic development partnership is a global first, and will change the way we collectively tackle illegal migration through new, innovative, and world-leading solutions.

Logistical problems abound, as the Financial Times observes, “Rwanda is not only one of the poorest countries in the world, it is the single most densely populated state in Africa.”

And yet, it is one of the richer sub-Saharan African states, ranking 16th out of 47. If geographic (and, possibly, cultural) proximity to a refugee’s country of origin are to be taken into account, and assuming the financial incentives Rwanda is to receive render it capable of providing proper accommodation and care, the move would appear justified.

This latter question of providing adequate conditions, however, is a serious one. Rwandan opposition and international NGOs maintain that the plan is financially unsustainable and will stretch the country’s administrative capacity to the breaking point, and possibly aggravate Rwanda’s human rights issues. The senior legal officer for the UN Refugee Agency in the UK, Larry Bottinick, described this sort of agreement as “eye-wateringly expensive” and often in violation of international law.

And yet, Patel’s talk of setting a precedent is interesting. Assuming the plan can be made to work in the medium-term, it may serve as inspiration for similar arrangements to be reached with other African states, reducing the burden on Rwanda—as well as with countries in other regions from which large numbers of displaced people are fleeing. This will greatly alleviate the pressure on European countries and facilitate the eventual return of refugees to their country of origin.

Crucially, any new international architecture for asylum processing must avoid turning western aid for accommodating refugees into a perverse incentive for countries to allow population displacement in their neighbors. To the contrary, having to accommodate refugees from one’s neighborhood should serve as an incentive to work harder at fostering regional stability.