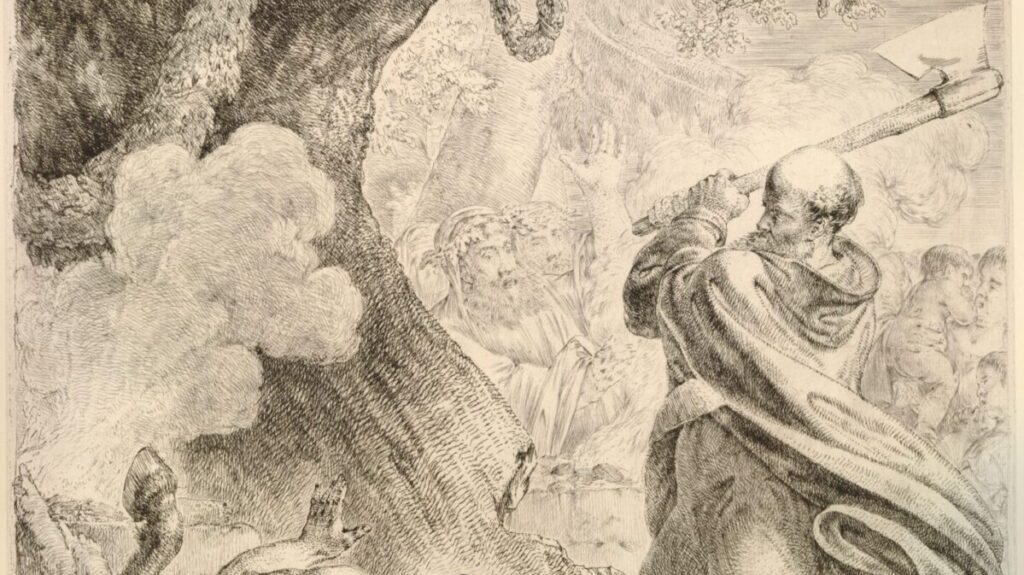

1781 etching of St. Boniface felling a large oak tree venerated by pagans to convert them to Christianity.

© The Trustees of the British Museum, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0.

A few years back, a German whose name I never learned commented regularly on my blog. His remarks were usually intelligent, but almost always critical—especially of anything having to do with Christianity. Though a practicing Christian, I almost always learned something from him. And the most memorable thing I learned was that the religion that built Europe is today destroying it.

“I will never forgive the churches what they have done,” the man wrote once. “They are killing my country.”

He was talking about the support of Germany’s contemporary churches, both Catholic and Protestant, for mass immigration. To this man, leaders of today’s churches care more about the abstract ‘Other’ than the well-being of their neighbors. Their sentimental humanitarianism has opened the floodgates to foreign peoples who know nothing of the culture, the traditions, and the folkways of the Germans, and who care even less.

In a bitter irony, that most of these newcomers are Muslim means that church leaders have enabled Christianity’s historic enemies through the symbolic gates that, in 1683, a pan-European Catholic army successfully defended against the Ottoman invaders outside of Vienna. With the observance of the Christian faith flat on its back on the continent where it first grew, European Christian bishops, priests, and pastors have blessed the importation of a foreigners who bear a culture and a faith that will either neutralize Christianity (because formal secular neutrality is the only way of keeping the peace in a multi-faith society) or displace it.

“German Reader,” as he called himself, was himself an atheist, but his anger at Christianity was entirely over the capitulation of its leadership to the kind of mindless progressivism whose adherents wouldn’t even defend the conditions that make secular liberalism possible. If memory serves, as angry as he was at the politicians for weakening secularism and liberalism by importing mass number of migrants who are neither secular nor liberal, he was even more shocked that Christians signed on to these policies, given the undeniable hostility to Christianity throughout the Islamic world.

I lived in the United States at the time, but from what I could tell, German Reader’s complaint was not only valid in Germany, but all over Europe. Certainly Pope Francis’s policy on migration—open doors, without exception, and forever—makes him the high priest of the Great Replacement. In Hungary, the government recognizes that Christians and secular humanitarians have a moral obligation to help refugees and those suffering from war or persecution, but its policy is strongly oriented towards aiding the suffering in their own countries, or elsewhere. Hungary does not recognize that the only way, or the best way, to help refugees is to grant them permanent residency in Europe. And it also recognizes that very many migrants are not refugees at all. Alas, Hungary is an outlier in Europe on this front, and is even condemned as hard-hearted conservatives by Western Europe’s mush-brained liberals.

Since moving to Europe a couple of years ago, I have encountered practicing, Christians, both Protestants and Catholics who hold orthodox beliefs, who have lost faith in the clerical leadership of their churches. The reasons are varied, but almost entirely have to do with what they regard as the sellout of the faith to the post-Christian world. Indeed, last week the Finnish Lutheran laywoman Päivi Räsänen endured her second trial for blaspheming against LGBTs, in part for a 2019 tweet in which she publicly asked why the state Lutheran church was participating in that year’s Pride parade.

In Germany, some of my Catholic friends are so disgusted and appalled by the heretical liberalism of a majority of that country’s Catholic bishops that they are coming to a breaking point. Two weeks ago, one faithful German woman told me she is trying to figure out if it is possible to disaffiliate from the Catholic Church in Germany while remaining in communion with Rome through a non-German diocese.

Another believing Catholic friend, this one a husband and father, tells me that he and other Catholic families he knows are making plans for the total collapse of formal German Catholicism. They believe, as orthodox Catholics must, in the institution as God’s instrument, but place no credibility in the faith, courage, and visions of the clergy as a whole. This particular Catholic man said that he and his community of theologically conservative believers have made peace with the fact that sooner or later, they and what few priests and monastics they can find, will be de facto on their own.

Conditions aren’t nearly as dire for theologically conservative Christians in the United States, but Americans are well on their way to following in Europe’s deconversion footsteps. The numbers looked dire just prior to Covid, and have accelerated since then.

Mainline Protestants continue their long decline towards extinction, with most conservative having been driven out of those denominations into Evangelicalism or Catholicism.

Though conservative U.S. Catholics celebrate converts moving over from the liberalizing Mainline, the truth is that for every new convert, there are 6.5 Catholics who leave the church. The bishops never recovered their authority after the serial humiliations of the sex abuse scandal. The church is hemorrhaging members, and those who stay may or may not agree with basic Catholic teaching (e.g., only one-third of U.S. Catholics polled in 2019 agreed that the Eucharist is in some real sense the Body and Blood of Christ). While Pope Francis routinely berates conservative U.S. Catholics, he sends bishops that delight the American church’s progressive wing—the faction least likely to hold on to believers.

Meanwhile, Evangelicals are fractured by fallout from the Trump years, with a many-faceted schism developing between younger Evangelicals who loathed Trump, and older hardliners. Some of the anti-Trump Evangelicals are moving to the theological left, while others are radicalizing further to the right out of frustration with what they consider to be an out-of-touch ‘normie’ conservative leadership style. A pastoral approach defined by ‘winsomeness,’ which grew in popularity in the 1990s and 2000s, is now thought wimpy by some angry young Protestants.

It’s not hard to understand their feelings. Over the past decade, American society has gone through, and is still going through, an astonishing cultural transformation. The most radical form is the mainstreaming of transgenderism. Ten or twenty years ago, if you had said to most Christians that within a decade or two, it would be legal to sexually mutilate children through chemicals and surgery, to change their sex—and that doing so would not only be permitted, but encouraged as the latest iteration of progressivism—few would have believed it. And if you had said that by 2023, some states would pass laws permitting the government to seize minor children over the age of 15 from their parents, for the sake of transitioning the trans-identifying child over the parents’ objections, Christians would have said America would by then be a tyranny.

Yet this is exactly what has happened. And most Christians leaders have sat mutely by. Why? A big part of it has to be what the Evangelical cultural critic Aaron Renn, in his forthcoming book Life in the Negative World calls the failure of Evangelicals (and I would add nearly all U.S. Christians) to recognize “that cultural conditions have fundamentally changed for Christianity.” The U.S. has been Christian for so long that its leadership class—and most followers—are psychologically unprepared to grasp that believing Christians are a minority. And, unless Christians endorse progressive politics, especially around sexual orientation and gender identity, they are going to be hated.

Many conservative Christians in America have doubled down on populist politics, apparently on the theory that voting for Donald Trump will turn things around. Whatever the merits of backing Trump at the ballot box, the idea that cultural decline will be reversed solely through political action is absurd. The Republican Party has held substantial political power, both in the executive and legislative branches of the federal government, since the early 1990s. And yet, social scientists have identified 1991 as the peak of American religious belief, observing a steady decline since then. Something else is going on.

As it now stands, the U.S. is not at all close to the European model of Christianity being irrelevant to public and cultural life, but this is the direction in which America is trending. As Americans are losing faith in all their normative institutions, American Christians are also losing faith in their religious leaders, who have greeted this unprecedented crisis with either capitulation or denial. The angry sentiment that the atheist German Reader held towards Christian leaders in his country is rising in the US, among lay Christians. Who can blame them?

Yet an alarming trend is now manifesting among a group of young, radicalized Protestants who spend a lot of time online. They are lashing religious belief to nationalism, hardline patriarchy, and reactionary militancy. Some openly flirt with white supremacy and anti-Semitism. Intense anger is their dominant spirit.

Though it has nothing in it about racism of anti-Semitism, a newly released book, The Boniface Option, captures the spirit of these radicals well. The title is a play off my own bestselling 2017 book, The Benedict Option, in which I made a case for why the example of the early Benedictines offers a strategy for the faithful in this post-Christian world. It centers around building resilient communities of traditional Christian practice, defining themselves as separate from the unbelieving world, but engaging with it.

Boniface Option author Andrew Isker, a young hardline Reformed pastor in Minnesota, believes this is too quietist and passive. He takes as his model the eighth-century Benedictine missionary who chopped down a tree sacred to a Germanic pagan tribe, thus commencing their conversion. Isker believes that Christians should cultivate hatred for wicked things, and attack them aggressively. If you want to know more about The Boniface Option, I reviewed the book critically in an ungated post on my Substack newsletter over the weekend.

What’s most troubling about the book is its pastoral focus not on managing anger, but on stoking it as a means of cultural aggression. It is impossible to blame Isker and his followers for being furious at the mass degradation of our culture (he calls it “Trashworld”), and the puniness of the Christian response. Europe is far more secularized than the US, but in my short time living on the Continent, I have become aware of some Christian groups—usually Catholic—who articulate and embrace a response akin to Isker’s. Again: when bishops, pastors, and other leaders are either collaborating with the destruction of Christian culture, or remaining passive as the barbarians sack the city, so to speak, what are good Christian men and women to do? Sometimes the flawed response from the Iskers—Catholic, Protestant, and Orthodox—is better than the lack of response from the more respectable religious authorities.

The problem, though, is that I personally lived out a version of the Boniface Option as a Catholic—and it nearly destroyed my faith.

Back in 2002, the clerical sex abuse scandal broke big in America. I was a writer at National Review magazine at the time. Because by then I had well established myself as a conservative and a public Catholic, I felt I had a special obligation to attack the bishops, priests, and others within the Church who had covered up for abusers, and created a culture of abuse.

Early in the scandal, a good priest warned me that if I kept doing this work, I was going to go to “places darker than you can imagine.” I thanked him for his caution, but told him I had a duty as a Catholic, as a father, and as a journalist to work as hard as I could to clean the church up. He blessed me, and offered to help however he could, but repeated his warning to be careful.

Over the next few years, I wielded my pen as St. Boniface did his axe, hacking away at the idolatries within the Church: the gay priest networks, the clericalism, the stigmatizing of victims and their families as enemies of the Church, and so forth.

Eventually I was exhausted. The evil tree still stood, barely moved. But I was ruined. I had lost the ability to believe in the claims of the Catholic Church. If I had not become Orthodox, I likely would have lost my Christian faith entirely. When I entered the Orthodox Church, I had been profoundly chastened, and knew that if ever I confronted corruption there, I could not allow myself to respond in the same way.

The meaning of this is certainly not that my anger at the Catholic abusers was wrong. These sins of theirs cry out to heaven for vengeance. Last week, a U.S. court ruled that the alleged serial rapist of seminarians, former Cardinal Theodore McCarrick, is too feeble at his advanced age to stand trial. Soon the dirty old man will face the true Judge. But in this life, he got away with his evil deeds. If you’re not angry at that, you’re not paying attention.

Yet I allowed my righteous anger to master me—and ultimately, to defeat me. If I had been more spiritually mature, I would have been better able to restrain it and direct it towards a constructive end. After all, there were Catholics who were just as angry as I was about the scandal, but who did not suffer the destruction of their faith. The priest who warned me in 2002, who has spent most of his life fighting for justice for victims, is one of them.

The same thing happened to me in a secular way around the same time, regarding the U.S. war on Iraq. Living in New York on 9/11, I saw the south tower fall with my own eyes. The profound trauma of the events of that day inflicted a deep wound on me. I wanted war on America’s enemies—and I was not discerning about who those enemies were. When the Bush administration said we must respond by declaring war on Iraq, I fully believed it. Anyone who doubts it, I thought, is either a coward or a fool.

Three years later—the same year in which I lost my Catholic faith, as a matter of fact—I realized that my rage at the Muslim terrorists who brought down the towers had allowed me to be manipulated by my government into supporting an unjust and idiotic war that has had catastrophic consequences.

“You must overcome your aversion to hate,” Isker tells his Christian readers. Let me tell you, readers, from both a religious and a political perspective, that is the road to hell. I’ve lived it. It won’t work—it’s far more likely to destroy you than your enemies—and if it does work, what kind of world will it create?

At the end of August, I spoke to a pan-European ecumenical (but mostly Catholic) Christian group meeting in Rome, the European Fraternity. These are young adult Christians, aged forty and under, who come together to build faith and fraternity, with an eye towards resisting the disorders of the post-Christian era, but firmly rooted in the faith. They love Jesus, but they’re not outraged about it.

This was the third year I’ve spoken to the group, and once again I saw serious Christians who, like their rash American co-generationalist Andrew Isker, are not deceived about the seriousness of the crisis, but who seem more keen on wielding a hammer to build rather than swinging an axe to destroy.

This is the way.

On the American margins, Christian radicals fed up with the advanced decadence in our culture, and the churches’ pathetic response to it, are talking themselves into baptizing Nietzsche. European Christianity—especially in Germany, the land converted by St. Boniface—knows all too well where this can easily lead. Nobody wants to follow the feeble, liberal German bishops of the present day into the abyss of apostasy and irrelevance. But the German bishops of around a hundred years ago had to contend with an extremely potent version of an angry Christianity that fused nationalism and force with rage and aggression. The result is a big reason why Europe is scarcely Christian today.

Now is the time for European Christians who haven’t been compromised by theological liberalism to speak out, and warn their American brothers in the faith about where sanctifying hatred leads. You may think you are chopping down an evil and malignant growth, but you may actually be hacking away at the roots of the faith—yours, and our civilization’s.