The European Conservative magazine went through a number of changes this Summer—and I understand more changes are to come. What’s ahead?

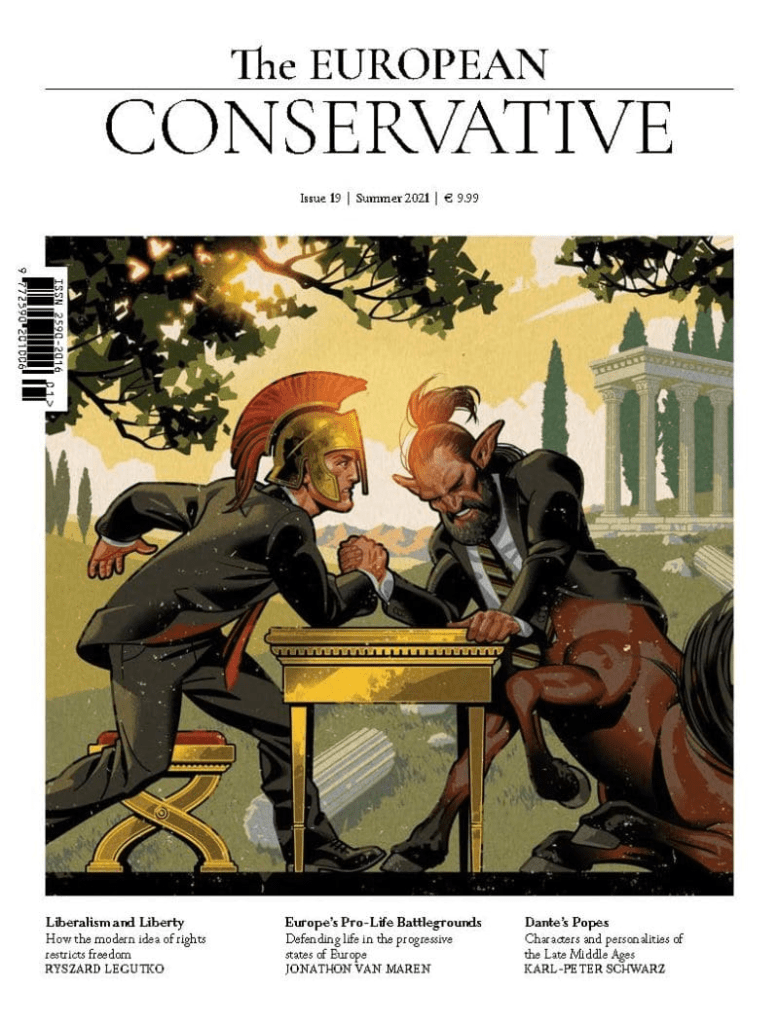

Many things have changed. And there have certainly been many ‘phases’ in the life of this little publication. It really began as a four-page newsletter put together by a group of friends. In fact, the first five editions were only between four and eight pages. I volunteered to serve as editor with the sixth edition and I slowly began to increase the page count—first, to 24, then 32, 52, and eventually 60. We’re now at 112 pages.

Now, in its new form—in what we might call its third incarnation—we’re reaching out to find new or undiscovered writers and thinkers in Europe and across the Atlantic. One of our objectives—one I’d really like to push now—has always been to make available in English the writings and thoughts of promising conservative thinkers, both young and old, from around the world. I’d really like to bring to the attention of English-language readers the work of conservative thinkers in, say, Latvia, Malta, and Portugal, or even Ukraine, Serbia, and Russia. I want to publish and promote the works of conservative intellectuals everywhere. We are also happy to translate their materials, too, since many of them do not necessarily write in English.

Separately, I also want to give other more established writers—people like Anthony Daniels or Ryszard Legutko, for example—the chance to not only write about politics and philosophy, which they always do, but about more personal things, the things they love: a favorite book, for example, or an antique chair they acquired, their favorite tailor, or their preferred private club or favorite pub in Lisbon, London, or Madrid. I think readers enjoy this more personal side of famous people very much.

Could you outline what the Hungarian involvement was in this third incarnation of The European Conservative ?

The first thing to keep in mind is that The European Conservative grew out of the activities of an organization called the Center for European Renewal (CER), which is best known for organizing each year the Vanenburg Meeting. This is a three- to four-day gathering held annually, always in a different place in Europe, that brings together different conservative academics, thinkers, and writers. Since the very beginnings of the CER, we’ve had active Hungarian participation. And, in fact, the CER’s current president is the esteemed political philosopher András Lánczi.

As I began to make changes to the magazine, I began to look around for ways to give it a more formal legal structure in the long-term, as well as a base of operations—and, ideally, funding. I considered various options in Europe for starting an NGO—Austria, Belgium, Switzerland—but it was just around this time that two things came to my attention: the activities of the new Danube Institute in Budapest, which was started by a man I have admired for decades—John O’Sullivan; and, secondly, the growth of the Mathias Corvinus Collegium (MCC) and its impressive range of intellectual activities, all headed up by Zoltán Szalai, another man whose vision I’ve come to admire.

I quickly recognized that Hungary was taking on a strong leadership role in the public sphere—one long ago abandoned by less courageous international conservative organizations. In doing so, it was helping to expand the “safe space” for conservatives everywhere. (It’s amusing perhaps to hear me use this expression, but it responds to a rather serious matter. What we’re encountering outside of Hungary—all across the West, really—is a cultural and political assault that should concern us all.)

The Dual Monarchy, here symbolized by Middle Common Coat of Arms of Austria-Hungary (designed in 1915).

With all this in mind, and given the deep respect I have for Hungary’s moral courage, it simply made sense to locate a new organization in Budapest. In addition, having been based in Vienna for 12 years, I also appreciate the historical and symbolic continuity of working in the two former seats of the Dual Monarchy—working and living in one city, and having related activities just down the river in the other.

How do you measure your reach? And how do you expect readership to grow in the years to come?

We’re tracking the numbers from Google Analytics, Facebook, and Twitter. What you see across the board is rather steady growth over the past few years and, naturally, that pleases me. There haven’t been any sudden spikes of growth, which is fine. But what I do see is very steady, sustainable growth among demographics that matter to me. We are discussing and developing a strategy not only to incrementally increase our output on the website, and thereby increase page views and number of readers, but also to position ourselves more and more as the ‘go-to’ platform for conservatives across Europe and around the world.

The cover of the 12th edition of The European Conservative, published in the Summer/Fall of 2015.

In terms of the print magazine, which is a quarterly, I am trying to be prudent. There is a tendency among many upstarts, especially here in Europe, to suddenly launch some massive initiative and immediately publish 10 to 20 thousand copies. I had discussions about this with my team and we agreed that we should start with three to five thousand copies of the print edition—and then, depending on the public response to that, we can later consider increasing the print run.

It’s worth keeping in mind that the previous version of The European Conservative was printed in very small batches of 200, 300, maybe 500 copies—maximum!—and we would typically distribute them in person, often carrying them around in our luggage to various conferences. So, the jump in numbers this year is quite significant. Of course, there are things we are planning for the website—podcasts, videos—that we’re hoping will bring even ‘more eyeballs to the site’ and more readers to the magazine; but that’s all still in the works.

You’re now irrevocably involved in a media landscape that’s skewed against conservatives and ‘out to get us.’ How do you think conservatives can map out a social media strategy that helps them popularize their ideas and which possibly culminates in them winning elections as well?

It surprises people when I tell them that I don’t think about elections too often and I really don’t concern myself with having a political impact. Some friends tell me this is because I’m too cynical about modern politics. Perhaps. I prefer to think that my disdain for the political process today is the result of recognizing that politics has achieved nothing for conservatives at all. We’ve lost so much ground that truly changing things for the better through standard political action seems far too difficult.

Instead, there are two approaches that I have been emphasizing more and more: first, to expand the “conservative media space,” which means pushing back against the cultural and media elites, in the hope of making it possible to once again have open discussions about topics that are currently verboten. One way to do this is by pushing back aggressively against the mainstream media through thoughtful yet provocative publications like The European Conservative. But we need many more such initiatives. I am constantly encouraging others to write more, disseminate alternative viewpoints, and maybe even start their own media projects. We need more publications, newsletters, and platforms of our own to help take back that “space” that’s been so aggressively taken away from us.

The other approach is to disrupt corrupt systems. I think that in nearly every sphere of human activity—academia, finance, media, etc.—we need more disruption. That’s the promise of homeschooling and alternative educational institutions. It’s the promise of cryptocurrencies and decentralized finance. What’s interesting is that the more such disruptive innovations grow, the more you see the “deep state” of each country—always in collusion with its Big Tech allies and Woke Capital—trying to stifle and even suppress them.

Disruption is needed, though it obviously terrifies most people. It’s a source of uncertainty. It’s difficult to manage. But the more the oppressive, liberal authoritarianism of the progressive Left spreads, the more disruption is needed. Take, for example, the higher education industry. When I look around the U.S. and parts of Europe, I see so many of those old, prestigious colleges and universities completely taken over by “woke zombies.” They’re all in the hands of the “politically correct” and they’re all pushing various interrelated agendas onto both students and faculty.

At the same time, you still have young conservatives desperately trying to get accepted into—or get an academic appointment at—places like Cambridge, Princeton, Sciences Po. This is outrageous, since these are the very institutions that are pushing the ideas and values that we conservatives are against. These institutions will stifle or suppress certain ideas until conservative academics have “taken a knee.” So I’ve completely changed my mind about all those institutions that I used to admire. Now I tell young people: forget those institutions. Walk away from them. You don’t need them. Peter Thiel got the message long ago. Start your own institution. Support one that better reflects your values. Make your own way. So, yes, I want to disrupt higher education in the same way that I want to disrupt politics and, in my case, the media. Forget Twitter. Build your own platform. In the meantime, join GETTR!

A couple weeks ago, the Hungarian news magazine Mandiner asked Tucker Carlson what person he would cancel out of history if he had the power. He said he would have shut down Harvard University in the 1960s. What would you do to disrupt the university scene and counter the ‘wokeness’ that’s gaining ground?

I find it all quite tragic. My parents are both educators, and I grew up respecting the academic world, admiring the oldest universities in the world. I grew up with the idea of the university as a place where you could read old texts, commune with the Greats, and exchange ideas and viewpoints—especially at venerable universities like Coimbra in Portugal, Salamanca in Spain, and, of course, Oxbridge in the UK. I love those old institutions. But they’ve been taken over—and completely corrupted—by the “tenured radicals,” as Roger Kimball [editor and publisher of The New Criterion] has put it. So, I agree with what Tucker said and I’d have canceled Harvard, too—though maybe I would not have limited it just to Harvard!

The countercultural revolution of the 1960s and everything that happened to the leading universities of the West during that time—particularly in the U.S.—has long been of interest to me. I am convinced that we’re still living with its after-effects—“the poison has worked its way into our souls,” as Harvey Mansfield once wrote about the legacy of the 1960s. When we look at American society and what happened to the nation’s top universities during the tumult of the 1960s, I think we have to conclude that much of the fault lies with the crumbling of the old WASP [White Anglo-Saxon Protestant] Establishment. Consider Yale, Harvard, Columbia, and other prestigious American universities: many of their presidents and administrators at the time were from the old establishment of the United States. In nearly each and every case, they capitulated to the campus radicals. The students took over university buildings, organized sit-ins, staged violent protests—and university administrators simply gave in. They didn’t fight back. In most cases, they gave in to the demands of the radicals. I think that was one of the first salvos in the “culture war”—and we lost tremendously.

Let’s come back to conservative movements around Europe. Hungary’s anti-pedophile law has been making waves worldwide. Do you think it was a good idea?

I’m very much a sovereigntist. I believe in national sovereignty. But I think we’ve moved much too far from that ideal over the last hundred years—increasingly moving towards an interconnected, interdependent world, with a weakened nation-state and powerful supranational entities that increasingly impose not just economic standards on countries but also certain values, principles, and beliefs. And these are often contradictory to a given country’s local or traditional values.

So, when thinking about the highly contentious law you referred to—or any other national law in any other country—I have to think less about the specifics of the law and more about the principles at stake: anytime a country is able to do something that its leaders have determined is for the common good of the nation and best reflects the values of its people, then I have to applaud—for they are resisting the globalist agenda and its values and, instead, are defending their own. This is especially admirable in the face of so much coordinated, international opposition—much of it shrill and unreasonable, and often driven by very narrow, special interests.

Hungarian conservatives have also been a driving force behind a new alliance of conservative forces all around Europe after their expulsion from the European People’s Party. Do you think there are actual long-term allies out there in the “European space” that Fidesz can count on?

I have to confess that I am generally repulsed by policy debates and electoral politics. I hinted at this earlier. My bailiwick is art, literature, philosophy, poetry, religion, and I very much believe that the ‘redemption’ of our world will come through those things—or, as Roger Scruton said: “Art has the ability to redeem life.” I like to remind people that politics is less important than other areas of life—and I point them to Andrew Breitbart’s famous statement that “politics is downstream from culture.”

I know we all need political allies. But for too long, in order to form coalitions, we have put aside our principles and have been cowed into not taking a stand. This is why Hungary’s courage is so impressive. Its principled stance has attracted many sympathetic people (as well as the ire of the global Left). And now I think Hungary’s natural allies are slowly emerging—among different sovereigntist movements of Europe, among national-conservative movements, and others. This is an immensely hopeful sign.

I’d like to add that I think what Yoram Hazony has done with the publication of his book, The Virtue of Nationalism, and with the launch of the National Conservatism conferences through his Edmund Burke Foundation, is also very exciting. It not only brings together a range of very intelligent people to discuss important ideas; the idea of national conservatism also seems to offer a way forward for many countries around the world.

In Italy, the center-right has maintained a consistent lead ever since the 2018 elections. But Lega is slipping and their voters are flocking over to FdI. Lega, however, does seem to be fighting an actual “culture war” in the background. Harking back to the Breitbart quote, do you think there is a significant cultural foundation upstream of Italian conservative politics?

As a reporter, I was once asked to write a long form essay on Italian politics, but I told the editor that it was a fool’s errand: there is no way to understand, make understandable to outsiders, and do justice to Italian politics. I find it so complex, and its political history can be so convoluted, and the country’s parties and political actors often so contradictory, that I sometimes think trying to keep it as one nation, made of wildly disparate regions, might not be the best thing to do. I even have some Italian friends who say, quite tongue in cheek, the best thing for Italy is for it to go back to how it was before the Risorgimento! It’s really several countries forced into one political unit. The North is quite different than the South; and even within those areas, some regions are significantly different from their neighbors. Such diversity is wonderful; but it also makes it difficult to talk about one sole intellectual or political tradition.

Having said that, I do think there is an intellectual tradition in 20th century Italy that could serve as a basis for political action, as a foundation for conservative politics. There were numerous 20th century intellectuals who provided solid formation to many of their students—many of whom later went on the great public service. Some of the names that come to mind are Gianfranco Miglio, Augusto del Noce, and Gianfranco Morra, recently deceased. Some of their students went on to become active in politics; others entered academia, but remain quite politically active. So there is a rich intellectual tradition there.

At the same time, I detect a cultural-intellectual divide. I think a lot of average bourgeois and working class Italians see ‘the world of the intellectual’ in their country as completely separate from and irrelevant to their lives. So, while there is a rather impressive intellectual foundation that once served as a source for political action—and could perhaps do so again—I don’t see it as being integrated with the lives of many people. In this regard, the ongoing work of the tireless Francesco Giubilei and his grass-roots intellectual organization, Nazione Futura, offers great hope for the country.

There is one aspect of the “culture wars” that has been making headlines lately, which is the effort to criminalize Catholic teachings on sexual morality. Who do you see winning? Do you think the left-wing establishment will be able to plow through? Or do you think the Vatican will team up with Salvini, Meloni, and others to try and stop it?

I don’t see the Vatican partnering with any of those leaders in Italy—maybe in the future. The current pontiff seems to come from a very different cultural and intellectual tradition than that of the leaders of the Lega and FdI. He has a completely different approach to political matters, a very different view of the role of the economy in the life of man, and—as seen recently—a rather unique understanding of liturgical tradition. I don’t see him partnering with any of Italy’s current political leaders on the Right.

Gender ideology is, of course, one of the current manifestations of the sexual revolution of the 1960s. In its various forms, it has acquired great power and influence and has developed an aggressive agenda. It think it’s clear to most people that the world’s economic and financial elites are generally on the side of that agenda (and have been for a while). And that’s why I think traditional Orthodox, Catholic, Christian, and Jewish beliefs and organizations have been censored by Big Tech and pushed out of the public square. But now, increasingly, those who hold such beliefs are also being pushed out of their jobs, schools, and homes. We’re entering, as Rod Dreher has said, a period of what can only be called persecution—a “soft despotism”—at the hands of today’s progressive ruling class. Sadly, I think it will get worse for anyone who adheres to traditional religious beliefs—especially on sexual morality, the role of the family, traditional marriage. And, in my darker moments, I predict a prolonged period of strife, unrest, and struggle. I don’t know how it will end up, but my outlook for the next five to fifteen years is rather grim and pessimistic.

As a Christian, I’m doing my best to remain hopeful. What keeps me going is the thought that it will all turn around again someday—perhaps in several decades. (We should all read The Fourth Turning.) In some ways, conservatives today are like those who made up the counterculture and the “back-to-the-land” movements of the 1960s. People like Rod Dreher and Yoram Hazony have even been urging others to form alternative communities based around traditional Christianity or Orthodox Judaism. I have also heard of more impulsive types buying land in rural parts of the U.S. or New Zealand, stockpiling wares, and beginning homeschooling programs for their children. I don’t know if they are right in doing any of this. We all have different roles to play. All I can say is that my role is to put up as much resistance to the progressive, anti-Christian onslaught as I can—until I am called to settle accounts.

Do you see a conservative intellectual movement in Germany? Do you think that’s even a thing that exists today?

Most certainly, though I don’t know how it compares to earlier periods and other intellectual movements in Germany over the decades. There were some rather impressive figures. I’ll mention one. I mentioned earlier the CER, from which The European Conservative was born, which was created in 2006. About 20 or 30 of us had gathered in the Netherlands to start it. Among us was Roger Scruton, now deceased, but also an elderly, very famous German noble, Caspar von Schrenck-Notzing. The author of numerous important books and a prolific journalist, he published a magazine called Criticón for decades. A prolific writer and intellectual entrepreneur, in the ’60s and ’70s he was part of a vibrant intellectual movement in Germany. Sadly, he died in 2009—and I see few men of his caliber today.

There are, however, signs that something is happening in Germany: a return to intellectual conservatism. In publishing you can point to the appearance and growth of magazines like the beautiful Cato and newspapers like Junge Freiheit. In Berlin, you have the Bibliothek des Konservatismus, which has an impressive and growing collection of materials, and which holds occasional seminars and workshops. You also have the more contentious Institut für Staatspolitik in Schnellroda. Although there seem to be some questions about its current direction, they continue to publish a well-regarded, high quality journal called Sezession.

Let’s go somewhere significantly more encouraging: Poland. PiS seems to hold its position for now, but Koalicyja Obywatelska is surging in the polls, along with the other major opposition contender, Szymon Hołownia’s Poland 2050, slowly slipping. The two major opposition blocs self-identify as right-wing. Are you comfortable calling them ‘conservatives’?

[Laugh] I question the use of the label ‘conservative’ all the time—despite the title of our magazine! This is actually a discussion I like to have with people all the time: what do you mean by ‘conservative’? What does conservatism mean, if anything, anymore? These are question I’ve always liked to explore.

When I came of age in the 1980s, there was a very robust and rather well-defined conservative tradition in the United States. I was fascinated by its leading thinkers and writers, its organizations and publications. Here in Europe, it’s an obviously completely different situation—not only because there isn’t one nation or political community but also because of the many linguistic traditions. Even within one country, I can see several different conservative or right-wing traditions, each with their affiliated parties, often with completely different or even partially contradictory platforms. All this make perfect sense to me because they’re each responding to the needs of different people in that country, different constituencies. They are all ‘conservative’ or ‘right-wing’ in different ways, each putting a slightly different emphasis on economics or social matters, for example. But at their core, there is something which makes them all part of the European Right. (And exploring what is at the core is one of the great joys of my work.)

I know some are concerned by some of the variants of conservatism in countries like France, Poland, and elsewhere. But I think a far greater threat to civilization—particularly in countries like Spain—comes not from the Right, in any of its many different manifestations, but from the abstract, secular humanist ideas on the Left. These are ideas that, in one form or another, seek to establish a regime that would then impose one model on the rest of us. I don’t see this push from most of those on the Right.

Let’s talk a bit about a growth area of European conservatism: Nordic conservative movements. Do you see anything to look forward to in that regard?

I lived and studied in Denmark about 15 years ago. While there, I remember coming across a collection of essays published by a group of young academics and policymakers titled Den Konservative Årstid (The Conservative Season). Now, I don’t read Danish but I stayed up late at night translating parts of the book, word by word. What impressed me was that I kept finding references to people like Russell Kirk, Eric Voegelin, Friedrich von Hayek—all heroes of mine and, to some degree, heroes of the intellectual conservative movement on both sides of the Atlantic. That was the first time I got a sense that something was changing on the Danish Right. “They’re discovering a tradition of conservatism shared with other Western countries,” I thought at the time. The book was a hopeful sign.

While in Denmark, I also got to know the Dansk Folkeparti (Danish People’s Party) and was very impressed with then-head of the party, Pia Kjӕrsgaard, and Søren Espersen, a member of the Christiansborg Parliament. The latter was especially impressive: charming, erudite. I recall we had a long and lovely chat about conservatism, literature, Shakespeare. He seemed to represent exactly the kind of conservatism that I have often tried to describe in my own writings, that I try to promote in various ways in the magazine: literary and thoughtful. These experiences also told me that there is hope for the future of Danish conservatism.

Regarding Sweden, I’ve had the chance to go up to Stockholm and Uppsala several times over the years, and to speak to different conservative and right-wing student groups. I’ve been similarly impressed. Everyone I met was widely read in the broader conservative tradition—that is, the tradition outside of Scandinavia and even beyond Europe. They knew all the names of the great thinkers and writers who helped give shape and form to both the Continental conservative tradition and the Anglo-American tradition, and they all seemed intimately familiar with a wide range of conservative ideas.

So, Scandinavian conservatism is most certainly ‘a thing.’ Other countries and regions of Europe also seem to have emerging talents on the intellectual Right. And yet, when time comes for such people of ideas to turn words and thoughts into action, it seems to me that the traditional party system slows them down. Putting it differently: you have these vibrant intellectual movements emerging in different countries—Denmark and Sweden, Italy and Spain—people with great ideas rooted in traditionalist conservatism, and yet, somehow, when these young people make their way into politics through their established parties and local party bosses, all their fresh ideas get watered down or pushed aside, their values dissipate, and their principles crumble. I think this is one of several reasons why conservatism rarely ever makes it to the policy level—particularly in the West.

I thus think that one of the most basic problems with politics as we know it today—which is too often based on Machiavellian compromise, consensus-building, and just ‘getting along’ with the opposition—is that it entirely forsakes principles for the practical. We need to propose instead a return to ‘first principles’ (which is essentially what a group of European intellectuals sought to do in 2017 when they issued the so-called “Paris Statement“). But first we need to “open up the space” in which such principles can even be discussed.

This circles back to my earlier statement: my fundamental belief that we need disruption. The conventional approach to politics—the ‘business-as-usual’ approach to politics, which requires that one be less idealistic and more pragmatic in order to ‘get things done’—is precisely what has led to so many of our defeats over the years. This approach has failed the conservative cause for decades. It’s time for something different. It’s time we were more courageous and firmer on matters of principle—like the dignity of human life, like national sovereignty, like sexual morality. It’s time we stood our ground without flinching. Perhaps then we will finally see some real change—and help save what remains of our civilization.

The interview was originally published at Mandiner.hu. It has been edited for length and clarity.