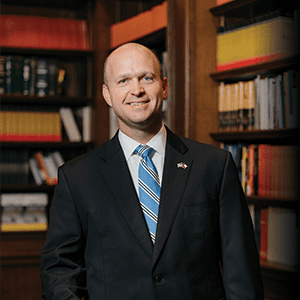

In the early 1980s, a group of conservative activists and intellectuals—led by the legendary Edwin Feulner, Joseph Coors†, and Paul Weyrich†—seeing a need in Washington, DC, for a think-tank to serve the policy needs of the new Reagan Administration, founded the Heritage Foundation. Nearly five decades later, it remains one of the leading organizations on the American Right. In 2022, Dr. Kevin Roberts became the organization’s seventh president. The European Conservative caught up with him for the following interview during a recent visit to Budapest.

Thanks for the question—and thanks for your time and for your work. As I sit here [on November 30], I am one day away from my one-year anniversary of being with Heritage. So, I have already started doing a lot of this [planning]. The headline is we are optimists. I am supernaturally joyful, and even hopeful, about this life, and this world, in spite of all of our challenges—if, and only if, conservatives learn what time it is in America.

This is the point in using that metaphor: we have a similar situation [now] when it comes to ‘self-governance,’ which is the phrase I like to use because I think it is more philosophically accurate (though people often prefer to use the term of ‘freedom’). We have very few minutes left on the ‘self-governance clock,’ if you will. And I think that of all of the policy institutions on the Right around the world, the Heritage Foundation is best positioned to move that clock backwards.

The point is that Heritage understands that we have a limited amount of time to take back the American Republic. We are blessed with the financial resources—from a very broad swath of people around the world and some ‘white knight donors’—that give us, frankly, the independence to say what the truth is. My colleagues are anxious to wage those battles—and are cautiously hopeful about winning them.

Yes, all of those; but I want to be really clear about this. So let me issue my usual caveat: although what I said sounds institutionally arrogant—as if there were a lot of hubris—it isn’t. There is actually great humility. We would prefer the situation to be different; we would prefer there to be many other institutions on the Right willing to fight—willing engage in ‘knife fights’—but they don’t exist. I might name names; but it is not what I do.

The point is that Heritage understands that we have a limited amount of time to take back the American Republic. We are blessed with the financial resources—from a very broad swath of people around the world and some ‘white knight donors’—that give us, frankly, the independence to say what the truth is. My colleagues are anxious to wage those battles—and are cautiously hopeful about winning them.

We lost one battle last night [with the defeat of a religious liberty amendment by U.S. Senator Mike Lee on a same-sex marriage bill]—and we are devastated. But we are not surprised. We also know that from that defeat we can take the fight to the courts. And we will win there, ultimately. It is going to take a year or two; but that fight ought to galvanize the American political Right around what Heritage has been saying.

I can take no credit for this because Heritage has been saying it for a long time. But if religious liberty is under assault, then everything is under assault in America. That’s what time it is in America. And for all these reasons, Heritage is best positioned to wage that battle.

Me, too.

It is—but I kind of like that!

You have prompted the potential for a really long response! So I will be very careful and concise because it is such a great question.

To my way of thinking, as a Burkean conservative, it is the question—and the reason it is the question is because conservatism rests upon principles.

I came of age as a conservative—in fact, I had often referred to myself as a ‘recovering neocon’—when I discovered Russell Kirk, mind you, after earning a Ph.D. in American history from a major public university. It was after that and it was during that time that I—sorry to point at you, but it is out of great celebration and our fraternity, as I see your response on your face!—founded a Catholic school in my home town [of Lafayette, Louisiana].

I won’t go into the details about that school, but I realized then that whilst the conservative’s fight ought to include policy and politics—it is really about fighting for our institutions. And as the lone conservative graduate student in the history department at the University of Texas, I had experienced the Left marching through the institutions. Although I was treated very well by the faculty, it was clear to me then that we had to create a parallel set of institutions—and this is why I sometimes call this the ‘Second American Revolution.’

So, to answer your question: what does America need now? Or what do American conservatives need to focus on? We need to mentally transport ourselves back to the 1770s and 1780s—or to whatever point it was when people started realizing: ‘we are going to win this war and we are going to defeat the British Empire!’

In Washington, however, everyone has started worrying about whether we really have the institutions to sustain self-governance—and the answer is ‘no.’

Keep in mind that I am a very devoted Kirkian, so I have great gratitude to the Romans, to the Athenians, to the Hebrews—but also to the great British tradition. This is our cultural inheritance—whether we are in Washington or in Budapest. So, what American conservatives have realized is that we need to honor that tradition by building institutions that reflect our style—not just of government but of civil society.

Although I generally try not to put an adjective in front of ‘conservatism,’ I am kind of enamored with the idea of ‘dissident conservatism,’ especially since I am someone who is often described as a ‘disrupter.’ Frankly, this is a label that I relish.

Sure, it sometimes doesn’t square with ideological friends of mine who say: “Kevin, I don’t understand how someone who has built two institutions—one from scratch, a college—and led two policy organizations, someone who is very much an institutional conservative, can say explicitly that many institutions need to be torn down. That seems like decidedly not conservative.”

That’s a fair point. But I am a scholar of the American Revolution—and I would have then, as a conservative, been very happy to literally tear down any British institution that violated my worldview and erect, upon its foundations, new ones.

We do—and I love that, too. It reminds me how limited I was when I originally began thinking deeply about conservatism. I have since realized the reality of what I was doing in starting the school that I did—which, by the way, is now flourishing 16 years later—and then leading Wyoming Catholic College as its second president, something that came out of the John Senior tradition. [Editor’s note: John Senior (photo, right), who passed away in 1999, taught at the University of Kansas in the 1970s, was the co-founder of an immensely successful experimental program called the Integrated Humanities Program. The motto of this program was nascantur in admiration—let them be born in wonder.]

You want to talk about tearing things down and building things up? Here, I think I am a ‘Seniorite.’ True, I am more joyful than John Senior was; but I am philosophically there, right where he was, and—and this is the point—I was doing that before I really knew why.

We have a lot of thoughtful conservatives in the U.S. who do too much thinking about why—and not enough doing about why. This kind of comes full circle to what the Heritage Foundation is really up to—not just under my leadership but also during its initial inception, with Scaife and Coors and Feulner, the last of whom in particular is a great friend and mentor.

I am hopeful about things because I see new institutions popping up all the time, whether they are explicitly conservative or whether they are simply neutral platforms like the University of Austin, which will literally open in the shadow of my alma mater, the University of Texas. There is nothing more glorious than what is happening in that city.

I could drone on and on about this; but I want to sum up my response in this way: I could not agree with you more on the advice you give to younger people about forgetting the legacy institutions. I think the institutions you mentioned—and many others, too—are too far gone to be saved. And yet they have endowments that are far too large. We have too much work to do to think that they are actively going to implode on their own. They are, however, in a slow-motion implosion. We just need to sit back, drink bourbon, smoke a cigar, and celebrate the hell out of it—while we work our butts off during the daytime to go and wreck those institutions. That is the spirit of the American Revolution.

A truly great man …

We do.

I have to start my response in the most authentic way: as a Catholic. I understand that not all of your readers are Catholic, and some may not even understand, but I have to answer the question honestly: the source of my hope is in receiving the Eucharist, Our Lord, every single day. There is no other explanation; and that is a great mystery—to you and me as Catholics, and probably more so to our friends who aren’t Catholic. I say that with a smile on my face, having had many friends ask me: how is it that you can believe in transubstantiation?

The point is, if there is a corollary to the Eucharist in another person’s faith—which, as a Catholic, I would say there isn’t but, if there is—then go to it; go to it every single day, multiple times a day. You and I can avail ourselves of Our Lord literally every day; and so, do so.

But to answer your question in a more secular way—as someone whose religious calling is to exist in the secular world very happily—what gives me hope is institutions. And what gives me hope as an American is that America is still [politically] a 50/50 country.

Yes, the recent mid-term elections did not go as well as we would have liked. But we ought not have so much hope in the Republican Party. Rather, we should have hope in the conservative movement; we should have hope in the American people; we should have hope in places like Hillsdale College and my friend and hero, Larry Arnn [president of that college] (photo, left), and many, many others. You know, we talked about John Senior; well, we need more Arnns, too, to give us all an example of hope.

But ultimately the reason I have hope is that I spent the last couple of days walking some of the streets of Budapest and there are joyful people here. There were also joyful people earlier this week, when I was in Warsaw. There are joyful people—tens of millions of them—in the U.S., not just in my adopted home state of Texas but in my new home state of Virginia.

Do you know why? Because they know what time it is. They know that centralized government, and the World Health Organization, and the European Union, and others, are trying to take—or, rather, have already succeeded in taking—some of our freedom. And so, it is incumbent upon us—those of us who have been given the great privilege of fighting against this take-over, whether in tiny or big ways—not to despair.

I have heard that, too. If despair is the greatest of sins—or one of the greatest—then we have to pray specifically (and here is an ecumenical statement) for grace from the Holy Spirit for us not to despair. And perhaps the best way to do that is—this is another thing I think and pray about a lot—to immerse ourselves in beauty. And I’m inspired sitting here in Budapest, surrounded by these hills, with the historical renovation that is going on here: it is a gigantic embracing of Hungary’s beautiful past.

Additionally—and I am trying to find a polite, non-profane way to say this—it is also a gigantic get lost! to the EU about erasing the historical memory—which encapsulates a ‘hopeful’ conservatism.

Exactly.

It is! It will never go away; it is just part of who I am.

I want to react positively to something you said about our ‘activism’ at Heritage: Saint Thomas Aquinas would remind us that the best activism comes from the best contemplativeness. And so, for me, as the leader of what I think is the most influential conservative policy institution in the U.S., it can’t just be about activism, as important as that is; our activism must spring from our understanding and appreciation of the source—as a reminder of the truth on which that activism is based.

And therein lies the task of being an educator and reminding people—especially fellow conservatives—about the beauty of art and the beauty of architecture. I do this imperfectly because I get pretty fired up and really love our activism. More and more, however—especially in the last three or four months—I have been explicitly saying that as conservatives, we have to remember our cultural inheritance. The reason we want to fight isn’t because an issue in a given state is a political opportunity; it’s because it is a means to re-achieving the redemption of American culture.

I didn’t expect to think about John Senior so much in this interview, but it strikes me—and I knew this already, he was so right—that what he also was working on was the restoration of American culture. And I think whoever the president of Heritage is, he or she should be doing that—because our organization was founded to always straddle activism and contemplativeness.

If you think about our policy scholars, they are not writing in a vacuum; they are writing for the purpose of affecting policy change. But if they only write about legislation, and not about the foundational principles on which that legislation rests, they aren’t doing their job.

This is a tough question; but it is a wonderful question—and I’ll give you a decidedly American response: not a pan-European think tank. And the reason is that one of the greatest crises in Europe right now—just borne out by what Brussels wants to do every week—is the demise of nationalism. As a historian, I understand all of the baggage that the word ‘nationalism’ has; but I mean ‘nationalism’ in its purest sense: pride in one’s nation-state.

Any nation-state is imperfect; but almost every nation-state has glorious chapters in its history—and its people ought to be proud of that. Therefore, I think what Europe first needs is a new generation of policy organizations that are focused on questions about each discrete nation. And I would encourage them—just as we have started to do at Heritage—to pay attention to local, regional, and provincial questions.

Second, what Europe needs is for those new organizations to come together to work towards one unified goal—that of dismantling the European Union.