Luis Robayo / AFP

Nicolás Márquez is an essayist and political analyst. He is a graduate of the faculty of law of the National University of Mar del Plata, the faculty of communication sciences of the FASTA University, and also of the Center for Hemispheric Defense Studies (National Defense University in Washington, DC). He has published 12 books, including El libro negro de la nueva izquierda (The Black Book of the New Left) written with Agustín Laje, La máquina de matar – Biografía definitiva del Che Guevara (The Killing Machine – Che Guevara’s definitive biography), and La dictadura comunista de Salvador Allende (The communist dictatorship of Salvador Allende).

Marcelo Duclos has a degree in journalism from TEA and a master’s degree in political science and aconomics from Eseade. A contributor to various media, he was a lecturer in World Economic Structure and was in charge of communications at F. Naumann between 2010 and 2022.

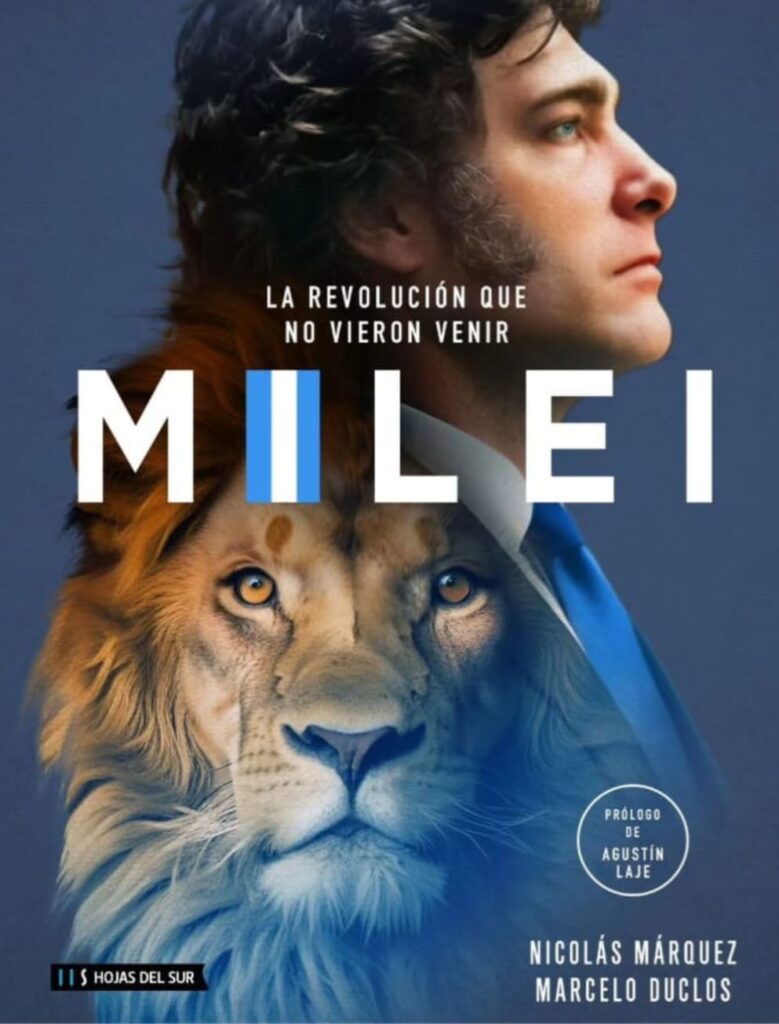

We discussed their new book, Milei, la revolución que no vieron venir (Milei, the revolution they didn’t see coming), which analyses the life, history, and dizzying rise of the first libertarian president.

Nicolás Márquez: For 80 years, we have been living in a system in which there were some untouchable concepts: social justice, the presence of the state, labour conquests, etc.—A whole series of very nice aphorisms, but they don’t work, and they are part of a systemic socialism, of an omnipresent state, which has been applied in Argentina by all the governments we have had, from the military to social democracy. Milei is the first who has dared to question the principles that have led us to ruin, and for that reason he was underestimated and taken for a madman. When he entered politics, he was treated as a comic character; but in three years, Javier Milei went from being a member of parliament to president, thanks to an underground and cybernaut majority. They didn’t see it coming and, even today with Milei as president, they don’t understand it—or, as they say in Argentina, they don’t see it.

Marcelo Duclos: Argentina has lived through a revolution with an abrupt change of paradigm. We could elect our representatives, yes, but only under the control of a political corporation that offered elections between the bad and the less bad. For the first time, with the arrival of Milei, there was a revolution against this model—and on a cultural level, because he broke all the manuals of political correctness that tell you what you can or cannot say, which is something that was absolutely necessary. The political corporation did not see what was happening, nor that social networks are nowadays more transcendent than the traditional media, and for that reason it has always been behind Milei. He has been underestimated time and again, and they even tried to bribe him, but now he is the president of Argentina. It is also a revolution in the economy: in the last period of analysis, the Argentine peso was the best performing currency in the world, when it had formerly been the worst; the fiscal deficit is over; and we have gone from having a risk index of 3,000 to 1,000 in just four months of government. They still don’t want to see what Milei is achieving; the opposition and its media only talk about his family, or whether he has four or five dogs.

NM: Milei has only 15% of the legislative power because Argentina renews deputies every two years: the congress by halves and the senate by thirds. Despite having so little muscle, he is standing up and fighting the battle. Those who thought that he was going to be a weak and frightened president, in the face of demonstrations and political power, are completely out of their minds. I think Milei enjoys the way he has been underestimated. And it is also important to note that his adjustments, which are dramatic, are being accepted by the average Argentinian; this represents a change in mentality compared to the short-termism that has existed until now.

NM: The only person I know who got the August election result very narrowly right was Marcelo: Milei got 30% and Marcelo estimated 28%. I thought that, more than an analysis, it was an expression of a wish. In fact, I asked Milei what result he expected, and he replied that 22% would be spectacular. Milei himself did not see the result coming.

MD: I had a dichotomy between my analytical tools—based on history and previous elections—and reality. When I asked people, everyone told me in the street, in the supermarket or wherever, that they were going to vote for Milei. My moment of revelation was when I was with a friend in a restaurant in a poor neighbourhood and I spoke on the phone with Martín Menem, president of the chamber of deputies and nephew of former President Carlos Menem. He told me, “Javier Milei is the next president of Argentina.” My friend told me it was obvious, so I asked the waiters and the cooks, and they all replied that they were going to vote for Milei. Then I realised it was going to happen.

MD: I am convinced that Milei’s result was greater than what the ballot boxes indicated. I was monitoring the elections in a wealthy neighbourhood in Buenos Aires. I’ve been doing it since 2003, and I’ve never experienced anything like this before. They took advantage of any moment to steal or change the ballots, and my phone was ringing off the hook with reports of fraud in different schools. They have done everything they can do, but, despite that, Milei has finally become president.

NM: Javier Milei represents what is new at the moment, but there were other parties before him. However, they were parties that represented the upper class and only reached 10% of the vote. Milei got votes everywhere, but his success was to compete in the poorest neighbourhoods. This is a huge achievement, because he took the vote from marginalised neighbourhoods where Peronism was winning and which have always sought to live off the state. Milei went to those neighbourhoods and people took to the streets to support him. He has won by offering exactly the opposite.

MD: Yes, and also because he spoke clearly to people and they realised he wasn’t lying to them.

NM: Sure, he was a footballer in a popular club, he was a rocker in a “Stones” type band, his aesthetics have nothing to do with that of a normal economist, and he used very coarse language to campaign, which he has moderated since he became president.

NM: Occasionally something slips out.

MD: Yes, but the analogy is very accurate.

NM: In Argentina, people had an abstract idea of the state. Milei’s great achievement has been to link the state with politicians. The cult of the state that existed in the mentality of Argentines was broken when it was linked to a political class that was totally discredited and full of thieves, corrupt people, and liars. By bringing the two together, people have begun to reject this statist mentality.

DM: It has begun to be understood that the only one who prospered was the politician and the only one who maintained his status was the bureaucrat. Unfortunately, it has had to go to the extreme for people to make this connection.

DM: Yes, he has brought back common sense; but, at the same time, never before have so many people understood the basic ideas of a candidate to address the necessary change. Our book aims to go deeper into those ideas so that people understand the scope of the reforms that Javier Milei intends.

NM: No, because he is the enemy to those who are losing their privileges. Milei has always said that he has not come to close the rift, but to deepen it, and that is why he provokes them. I would say that he even enjoys provoking all these minority feminist, LGTB, or indigenist lobbies, and the Left is totally disconcerted. Besides, all those who speak out against him are the ones who will never vote for him. They are lefties from whom Milei is cutting everything he can, and they are desperate. They are a coven: people who do not know how to produce and who are parasites on the state. As Milei says, society is divided between victims and parasites. The victim is the one who works and has to pay confiscatory taxes to maintain a whole parasitic structure, which Milei is dismantling with the famous chainsaw—one of his campaign slogans. Milei’s popularity ratings are skyrocketing and, as the economy improves, they will rise even higher.

MD: According to the polls, Milei has increased his support by two points. Recently a young man posted a video on social networks about a demonstration for the public university, in which precisely those who had ruined it were present. The young man left after two minutes because he realised that he was being treated like an idiot. Similarly, imagine a young Jewish man going to one of these university demonstrations to find himself surrounded by Palestinian, Hamas, and Iranian flags. There will always be a hard core who will never vote for Milei, but I think there is a percentage who will realise that they have been taken for fools. For example, there is the CGT union, which did not call any protest marches while wages were being radically reduced in the last four years, and which has now organised three strikes in record time. They are being exposed, and ever more people are realising it.

MD: I think there is a growing understanding in the world of the relevance and importance of what Milei is doing. We see that many world leaders—from Giorgia Meloni, who is ideologically closer, to Macron, who is much less so—show their recognition of Milei. However, the leader who meets with Elon Musk to discuss investments, comes to Argentina and has to give explanations about how he combs his hair, about his sister, or about his dogs. Unfortunately, for Argentines, his depth has not yet been recognised.

NM: Yes, and this book is an example of that. I am a right-wing conservative and Marcelo is a pure libertarian. That formula exists. In the government, the vice-president is a Catholic traditionalist; there has been a convergence of different sectors. In the economic sphere, the libertarian ideology prevails; and, in the cultural sphere, there is a clear conservative component, with alliances with Abascal, Meloni, and Trump. There are also people who come from Peronism and radicalism. Milei would not have been able to form a government with libertarians alone; he has been able to unite different wills.

MD: I disagree in one sense, because the Milei phenomenon cannot be seen as the success of libertarians with conservatives. There were barely a hundred of us libertarians, and we all knew each other; meanwhile, the conservative Right had only 1.5% of the vote. It is now, thanks to Milei’s government, that there are many more liberals and conservatives. It is to Milei’s credit that he has been able to offer a discourse that has transcended ideological limits. Our book aims to give political form to that discourse, to be a tool for debate against the Left.

NM: At the cultural level, Argentina has been immersed in wokism for the last 20 years. Milei is dismantling this ideology and he is doing it in a provocative way. In economic matters, Milei is going to try to take the market economy to the extreme, with the smallest possible state, to the extent that politics allows him to do so—that is, depending on the parliamentary support he can get. In economic terms, he will be as liberal as possible. And, in what is known as the cultural battle, he will seek to disarm the wokism that has infected Argentine society, and which has been sold by the state as public policy.

MD: I have no doubt about the possible scenarios, and I point them out in the book. The first is that the political corporation beats Milei, because they are willing to do anything—anything, even madness—to prevent Milei from ruining their business and privileges. The second is that Milei manages to increase the number of legislators in 2025, which would allow him to end the shackles that now limit him and turn Argentina into a world power.

NM: Javier Milei is a miracle. If we don’t take advantage of him, it will be our fault. Something like this happens once in a hundred years, and for me it is a good thing when he is treated like a madman. We need someone capable of taking drastic measures regardless of the costs. To me, it is a good thing that he is a reckless person.

MD: If Javier Milei succeeds in implementing his programme, Argentina will once again be the best country in the world. We are survivors. There is a huge hunger for growth and the ideal raw material to become a power again.