Fr. Benedict Kiely is a priest of the Anglican Ordinariate of the Roman Catholic Church. He administers aid and advocates on behalf of persecuted Christians in the Middle East. He shares his mission and concept, along with stories about the subsidiary nature of the support provided to small family businesses.

From childhood, I had an interest and concern for the persecuted Church in what was then the communist East. But I was a contented parish priest in Stowe, Vermont, until I heard—in August 2014, as Islamic jihadists swept through Iraq and Syria—that, for the first time in nearly 2,000 years, there would be no Mass in Mosul (the ancient city of Nineveh).

I remember praying and wondering how to help, and coming up with the idea of creating products marked with the Arabic ‘N,’ or ‘Nun,’ with which Muslims mark the houses of Christians (as “Nasranis” or “Nasareans”). Enlisting parishioners, we produced bracelets, lapel pins, and other items, and started sending the money to help in Iraq and Syria.

Even though it was fairly dangerous, I realised I must go to see what more I could do. So I went to Iraq in early 2015, when ISIS was just a few miles away. I have been to Iraq nine times, and also Syria and Lebanon. On my first visit to Iraq, in a refugee camp, a priest told me that I had a “call within a call,” to serve the persecuted. It took a few years of discernment, and ecclesiastical permission, before Nasarean.org was formed in 2016, as a 501c3, and I devoted my entire priesthood to the cause of our persecuted brethren.

Towards the end of 2014, a friend told me that I needed to go to these places, in order to speak with any authority. If you had told me, a year before, that I would go to Iraq and Syria during wartime, I would have laughed at the insane prospect. Quite clearly, the experience changed me. With the permission of my bishop, I began this ministry with no pay or support from the Church—actually with no salary for three years.

My “call” became clear: to devote my priesthood to aid and advocacy for the persecuted throughout the world, with a special focus on the Middle East. Those of a certain age will remember St. John Paul II speaking of the need for the Church to “breathe with two lungs”—the West and the East, but often that was interpreted as meaning just the Greeks and the Russians. Visiting Iraq and Syria, one is struck by the fact that the Church was born there; our roots are semitic. If you cut, harm, or destroy the roots of the tree, it will die.

Western Christianity, and Western Christians, not only do great injustice to their Eastern brethren who are being persecuted—by failing to support them as members of the Body of Christ—but they also harm themselves by losing their memory of where they came from. Visiting Armenia, the oldest Christian nation on earth, where our organisation has just started working (our fifth country), you see that glorious heritage, but also that constant hatred for the faith.

My visits have convinced me most profoundly that, if we proclaim the truth that we are brothers and sisters in Christ, it needs to move from nice-sounding words to reality. Just as we would help our blood relatives, how much more should we help our brethren in the Spirit.

Our focus is very specific, which differentiates it from most other charities. In the first place, it is not just a charity, it is a spiritual enterprise, founded and rooted in prayer, with prayer at the centre. The specific focus is advocacy and aid, which I believe are equally important, although often people only see the aid as valuable, which is mistaken.

Advocacy is me—possibly as the only Catholic priest in the world, certainly in the English-speaking world—doing this full-time. I speak, write, preach, and appear in the media to alert Catholics and others about the world-wide persecution of Christians—the most persecuted group in the world—which is barely covered by the media.

Whenever I speak, particularly in a Catholic setting, ordinary people are always grateful, but the normal response is, “We never knew anything about this.” I am very blessed that my bishop, of the Personal Ordinariate of Our Lady of Walsingham, sees this as an important ministry, even though I have to raise my own salary and all other usual priestly benefits. The other advantage of having been to some of these countries so many times is that, as my friend said back in 2014, I can speak with authority. I have, as Scripture says, “seen and heard” much, unlike many who staff think-tanks and other agencies.

My “call within a call” was certainly first to be an advocate for the suffering Body of Christ. Our aid is also very specific: we do one thing, which is microfinance small family businesses, so that persecuted Christians can stay in their homelands, and not migrate in order to work and support their families, or live dependent on charity. For a small amount—usually around $10,000—a family business can be created, which is something almost anyone can understand, especially in the U.S., where so many have a family business history. It is a positive act for people in the West who often feel despair at wondering how they can help their brethren. We survive completely on donations, with no support from the Church, governments, or other NGOs.

There are a couple of lines in the biography of St. Gregory the Great, In The Eye Of The Storm, by Sigrid Grabner, which partially answers why it is important to keep Christians in their homelands. Grabner writes that, even in those early years, the “Church continually purified itself by looking back to its roots and reflecting on where it came from. And those roots lay in the places where Jesus lived, where His apostles and their followers proclaimed the Incarnate God and professed their faith in Him despite suffering bloody persecution.” The Middle East is the cradle of Christianity. Christians were there long before Islam. They are a leaven in society, peacemakers, and the idea that those lands would be emptied of the disciples of Christ is an abomination. They want to stay and—even without security—if they have employment, they are willing to stay.

In places where relative peace has been secured, Christians are even returning: we are just about to support two businesses in Iraq with returnees from Canada and Germany. Even if Christians wanted to move, many countries in the West, including the United States and Great Britain, have taken a very small proportion of Christians compared with Muslims.

When we talk about the root of unrest in these lands, we are talking about hundreds of years of history, the creation of borders which never existed, religious and ethnic conflagration, and so much more. On my very first visit to Iraq, someone told me that I had to forget almost everything I thought I knew, because it was extremely complicated. That was a very good lesson. When we speak particularly of the persecution of Christians in the Middle East, we are, of course, principally dealing with Islam.

It is not anti-Muslim, or Islamophobic, to state a simple fact: wherever Muslims are in the majority, Christians suffer. This extends from regular persecutions and genocide, as in the case of Armenia, to constantly being second class citizens—the status of dhimmitude—without the same rights or prospects of the Muslim majority. Strangely, I have been told many times by the people in these countries that it was, and is, under the “strongmen”—the dictators, like Saddam and Assad—that Christians were safest. Syria was a secular republic and there was no inter-religious rivalry. All that changed with the rise of militant Islam, sponsored by, among others, Saudi Arabia and Qatar.

As I said earlier, our focus is very simple: family businesses. It is an incredible joy to know—for example—that, in just eight years, we have supported more than forty businesses in Iraq. That is not just forty families who have stayed and are building a future, but many of the businesses have several employees, so hundreds of Iraqi Christians have a future in their ancient homeland.

Our tiny charity is now in five countries: Iraq, Syria, Lebanon, Egypt, and Armenia. Some examples illustrate what we are doing: in the city of Qaraqosh, in Iraq, the most Christian town on the Nineveh Plain, which ISIS occupied and from which it drove out all the Christians, we are supporting a farmer and his family. We paid for him to get a well to water his fields. Iraq has been suffering from a drought for many years, and I remember, a few years ago, driving to his farm. All around us were brown fields; and suddenly, as we approached his farm, we saw green. It was quite biblical, the water bringing life and hope.

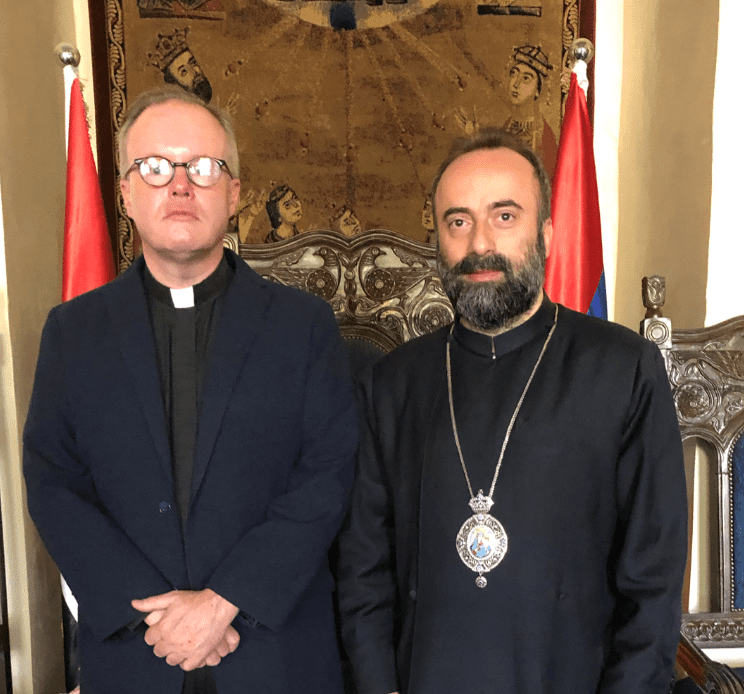

In Syria, through our ecumenical cooperation with the Armenian Apostolic Archbishop of Damascus, we have trained women in hairdressing and other skills, so that they can start their own businesses. We are doing a similar course in Armenia, training single mothers in tailoring and sewing, so they also can begin to create businesses. A number of the businesses are women-run, so empowering women in the Middle East is a great by-product of what we are doing.

The other project is creating shrines of Mary, Mother of the Persecuted, as a place to pray for our brethren. Always blessed and approved by the bishop, to show the importance of the shrine, the Icon of Mary, Mother of the Persecuted, is now in five locations in the world. Our latest was placed in Wyoming Catholic College, in May. We have other shrines planned; the key is the involvement and blessing of the local bishop. At these shrines we in the West can also pray for the fortitude needed as we face the persecutions which are coming.

Christianity is the most persecuted religion in the world. That is a statistical fact. It is at a level not seen since the time of the early Church, or the intense persecution by the Nazis and Communists. It is almost hard to name a country where there is not some form of persecution, and I include the United States and Europe.

Of course, in many places it is not to the point of death, but there is “white martyrdom,” where people lose jobs because they are Christians, or the civil law is inexorably restricting freedom of religion. Think, for example, of people being arrested in England for the “crime” of silent prayer or thought outside of abortion facilities. Terrible persecution is taking place all over Africa, especially in Nigeria, where thousands of Christians have died just in the last two or three years. Once again, in Europe, we can think of the case of Paivi Raissanen, a member of parliament in Finland, being charged with “hate speech” for quoting the Bible on marriage and the family. Christians in the West really need to wake up about the reality of persecution, and support our brethren now, because if we forget them, what will happen when we need their help?

Prayer is a first resort, not a last resort. Daily prayer for the persecuted is a duty, for life. Voters must challenge legislators about countries actively engaged in persecution. Why, for example, do we sell arms to Nigeria? Challenging trade and aid can be an effective way to bring change. Support charities that are actively involved: our little charity gets the help directly to those in need, and I need “Gospel patrons,” like those who helped Jesus and His disciples in their ministry, to continue this work.

One of the advantages of being small—and small is, indeed, beautiful—is that it is possible to see where donations are going. It is possible to start and support a family business for around $10,000—sometimes a little more, sometimes less. Supporting Nasarean.org and visiting our website helps Christians in their native lands—the holy lands where Jesus and His disciples walked—not just to survive, but thrive.