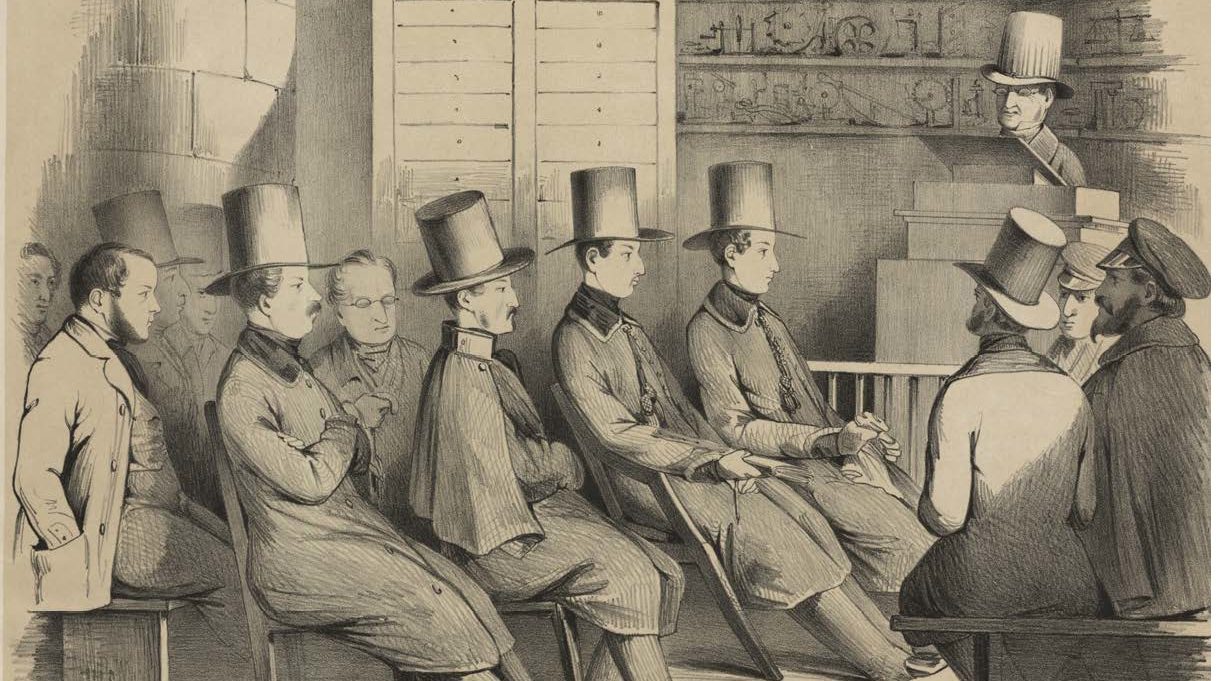

A lithograph from 1846 depicting Crown Prince Carl (later King Charles XV) and his brother Prince Gustaf attending a lecture by Johan Christian Lindblad in the Theatrum Œconomicum in Uppsala.

PHOTO: UPPSALA UNIVERSITY LIBRARY

“The best response to the violence is not hatred, but the daily courage of those who continue to believe that ideas are fought with other ideas. Never with violence.”

Johan Wennström has a doctorate in political science and works at the Research Institute of Industrial Economics (IFN) in Sweden. He is a regular contributor to the culture pages in the Stockholm daily Svenska Dagbladet and has written for City Journal and Quillette, among others. His most recent book, coauthored with Magnus Henrekson, is Dumbing Down: The Crisis of Quality and Equity in a Once-Great School System—and How to Reverse the Trend (Palgrave Macmillan, 2022). As of mid-June, the open-access version had been downloaded more than 34,000 times.

Cancel culture and related phenomena are outgrowths of what my coauthor and I call the postmodern social constructivist view of knowledge, which is a particular attitude toward the nature of knowledge. It holds that no objective, transferable knowledge exists and that truth claims are in fact ill-disguised power grabs. Thus, it becomes logical and legitimate to de-platform perceived opponents. The postmodern social constructivist view of knowledge permeates the entire Western education system today, but it arguably does the most harm in elementary and secondary education, which is the focus of our book. If schools do not teach students the elementary facts of the natural sciences, the social science facts that are important in each national context, and the most important ethical concepts, then students will go on to university or other life paths unprepared. Ultimately, they will be outsiders in their own societies.

Indeed, there is a strong connection between prosperity and diminished appreciation for education and academic tenacity. Economist Gabriel Heller Sahlgren’s report on Finnish education offers an emblematic example. Finland’s economic development was so quick that the country’s culture didn’t catch up and remained traditional for many years; this is why Finnish students performed so well in early PISA assessments. Yet as soon as the values of prosperity became dominant in the culture, Finland’s schools declined in quality. The main reason was the introduction of a less demanding and more individualistic pedagogy, underpinned by the postmodern social constructivist view of knowledge.

Our own country, Sweden, went through a similar development. Sweden’s remarkable economic rise during the period between 1860-1960 depended on the love of learning and hard work in the country’s culture, which was manifested in a high-quality school system. It was only when we had achieved a certain level of prosperity that we became open to embracing the postmodern social constructivist view of knowledge in our schools. Other factors were important, too, but it is hard to imagine the postmodern social constructivist view of knowledge being seen as attractive in the economically emerging Sweden of the 19th-century. The same is true for countries that are rising today, China in particular. That is why the Chinese are first in the OECD’s PISA [Programme for International Student Assessment] rankings—and why they may ultimately unseat the West as the dominant geopolitical power.

The attractiveness of the teaching profession hinges on which view of knowledge is institutionalized in schools. In what we call the ‘classical’ view of knowledge, teachers are considered central to education and the academic success of the students. However, the implication of the postmodern social constructivist view of knowledge is that the teacher, at best, has nothing substantial to offer and, at worst, is engaged in some form of oppression of students. When school systems adopt the latter view, it is logical that the social status of teachers is eroded.

It is true that the enchantment of education more broadly has been lost, and that is also due to the postmodern social constructivist view of knowledge. Why would anyone be enthusiastic about something that is about power and control, and pushing a certain ‘narrative’? If we returned to the classical view of knowledge and again came to see education as a project of human flourishing, both teachers and students would feel more engaged.

The one event that ultimately paved the way for the introduction of the postmodern social constructivist view of knowledge in Sweden’s schools was the Swedish misinterpretation of Nazi Germany’s education policy and its role in the Holocaust. The propaganda of National Socialism suggested that German schools were based on discipline and obedience to the teacher. Therefore, Swedish policymakers concluded that the traditional hierarchical teacher-student relationship produced individuals who blindly followed authority figures into evil and decided that the teacher-led educational model had to be phased out in favor of ‘student-centered’ pedagogy.

In reality, Nazi German schools were chaotic and disorderly, and dominated by Hitler-Jugend students who were encouraged by the regime to rebel against their teachers. The German youth was in other words actively taught to disobey authority and transgress moral boundaries in the classroom, which is likely why it later became one of the most active perpetrator groups in the Holocaust. But none of this was understood in post-war Sweden.

Sweden has gone farthest not only in institutionalizing the postmodern social constructivist view of knowledge in its schools, but also in marketizing its education system. Milton Friedman’s school voucher scheme was fully implemented in 1992. This combination of postmodernism and unbridled school competition for student vouchers has been unfortunate, creating toxic incentives for both public and independent schools.

Both categories of schools now compete by offering inflated grades, and this is made possible by the state’s refusal to define the knowledge schools should be teaching and on which their students should be graded. Healthy school markets, whether in Sweden or in other countries, presuppose a classical view of knowledge in national or subnational curricula.

I wholeheartedly agree with this. In the old Swedish education system, students were provided with six years of obligatory basic education and were then free to pursue either higher theoretical studies or practical training. It was a flexible system in which young people could find their vocation and quite easily change track. Since the late 1960s, everyone is expected—indeed required—to do theoretical studies for at least nine years. Opportunities to develop other skills are few and even the most practical subjects are theorized.

I think we need to return to a more differentiated education system, in which around 40% of each cohort go on to advanced theoretical studies. This would make it possible to raise the quality of theoretical education and allow people who are inclined to make other choices to find their own paths to flourishing. Ultimately, we need to recognize, as both David Goodhart and Michael Sandel have recently observed, that manual and intellectual labor have equal worth and dignity.

Formal education is not sufficient, but it is the basis for a culture of citizenship and civic commitment. If children are not taught, for instance, the history and geography of their nation, they will never feel at home in—or develop feelings of loyalty toward—it. Nor will they feel included in and inclined to contribute to society if they do not possess the basic knowledge of, for instance, mathematics and the natural sciences, which it is expected that everyone masters.

The most important and novel contribution of our book is the point that the most fundamental institution for the functioning of any school system is the adopted view of knowledge. It is here that scholars and policymakers should look to understand the success or failure of schools. Western education systems have in recent years institutionalized the postmodern social constructivist view of knowledge—and that is why these countries are trailing Chinese schools, for example, which remain committed to the classical view of knowledge and a traditional pedagogy. If the West were to return to this classical view of knowledge, it would yield a quick—and radical—improvement in the quality of education.

This essay appears in the Summer 2022 edition of The European Conservative, Number 23: 60-63.