The UN’s special rapporteurs are all appointed by the Human Rights Council, and the people who are chosen are those whose main interest is to condemn the West, colonialism, and capitalism.

Following the attack on Vermeer’s Girl with a Pearl Earring by activists of the ‘Last Generation,’ I set out to contact 20 of the most renowned museums in Europe to ask them what steps they have undertaken to prevent further attacks on their artworks. While many museums opted not to comment on the situation at all, the Uffizi Gallery in Florence, one of Europe’s most beloved collections of art, was open to discussing the matter. I was granted an interview with its director, Eike Schmidt, who shared some of his views on the security measures in museums, the legal ramifications in responding to such attacks, and the violation of the communication space in museums caused by them.

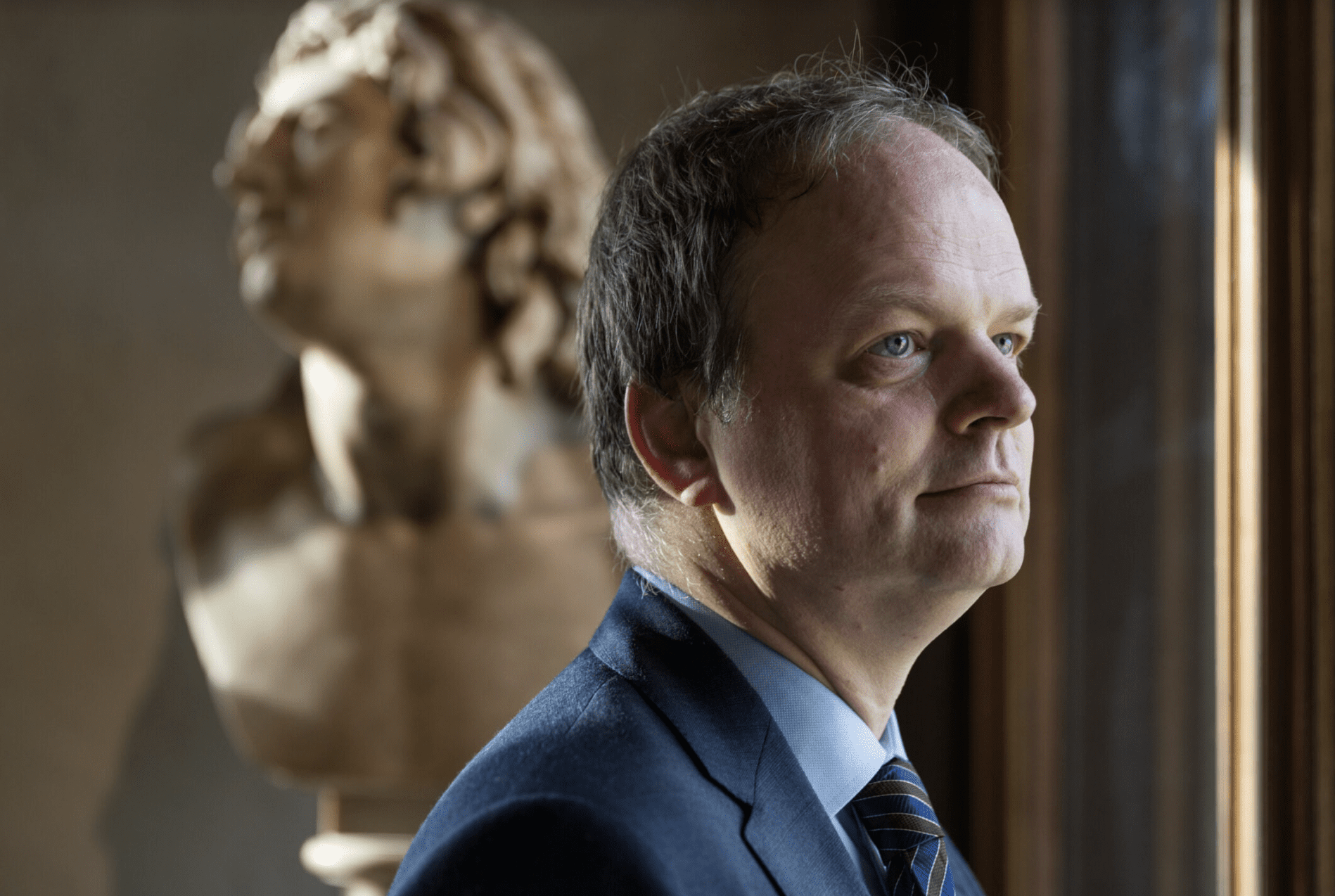

Eike Schmidt is a German art historian born in Freiburg. He studied medieval and modern art in Heidelberg, Bologna, and Florence. In 2001, he became a curator first at the National Gallery of Art in Washington D.C. and then, from 2006 to 2008, at the J. Paul Getty Museum in Los Angeles. Upon earning his doctorate in Heidelberg on The Medici Ivory Sculpture Collection in the 17th Century, Schmidt became director of the Department of Sculpture, Decorative Arts, and Textiles at the Minneapolis Institute of Art. In 2013 he curated an exhibition at Florence’s Palazzo Pitti before becoming the first non-Italian director of the Uffizi in 2015. Since then, he has made major strides in modernizing the infrastructure of the Uffizi Gallery. This includes updating security measures, but also constructing a website (which the Uffizi didn’t have prior to his arrival), the digitalization of the collection, and outreach to new audiences, most notably with an increased social media presence on Instagram and TikTok during the pandemic.

Of course, at the Uffizi we can’t disclose our security plans either, that would be nonsensical, otherwise people would be able to read it in your publication and prepare accordingly. But there are certain things that we can say and are happy to say. We have had a security concept in place since 2001 because of the terrorist attacks in New York at that time. We have metal detectors that you have to pass through, just like at an airport. We have not only maintained this system, we have also updated it in recent years. We really do have the security technology that you also find at the entrance to airports. That means that not only weapons and metal objects can be found, but also liquids. We have also specifically trained the personnel who operate these security systems.

As we have seen a lot of things over the past months, based on the security records of what has happened in our museum and in other museums, we are prepared for what needs specific attention.

A second important point is that we use video surveillance, we have both clearly visible video cameras, which is necessary so that the visitors understand that there is video surveillance, as well as video surveillance that is not so easily detectable in order to increase security for the visitors. Fortunately, we have not yet reached the point where we would have to ban cell phones, for example. Security technology should not interfere too much with the needs and customs of the public, just like at an airport. A visit to a museum should be a pleasure and an educational experience, and 99.99% of our visitors have nothing bad in mind. It is really a matter of finding out very specifically where a dangerous situation could arise. Of course, preventing a physical terrorist attack has a much higher priority, but since the attacks on artworks have happened repeatedly, including in our museum—and we reacted very professionally, which was lauded by the press—we have already trained our employees for future instances.

We always have, and this is a third important point, police units of the Carabinieri in our house. The moment such a situation arises, these units immediately take command. So they are not in-house guards who are left to deal with it on their own, but professional carabinieri who manage the situation. We have forces both uniformed and dressed in civilian clothes that patrol regularly. If they detect a situation indicated by our video surveillance system, they can also intervene within a few minutes or even seconds, depending on where it is happening.

Yes, but it is also the case that many countries in Europe and beyond have laws that restrict the actions of staff, some of which can be very restrictive. For example, staff in many countries are not even allowed to touch people and there are even strict guidelines about how staff can verbally interact with visitors. This is much more pronounced in certain countries than in others. Meanwhile, police security forces know exactly what they are allowed to do and what they must do to defuse such a situation and to resolve the disruption of public business. In this respect, one cannot always blame the museum guards, who are often volunteers, especially in smaller museums. They are often retired people who do this out of a passion for art, so one needs to differentiate very carefully. To reproach these people is certainly not fair. But since such disruptions have now been announced, it is important to train the employees in what they can do, what they must do, what they cannot do, and do not have to do. But that varies from country to country.

In various European and some American states, there are regulations that prevent museum guards from grabbing activists by the shoulder and pulling them away from the paintings. Museum guards are only allowed to call for help, i.e. call security forces and police, who then have to take action. In Italy, the police have to take command, and they can also give instructions to our employees on what they have to do to help. We also train for this occasion, and we are therefore very well prepared. However, it has to be said that the situation is much more difficult for small museums, which often also contain famous artworks; it is not even conceivable for them to have their own security forces with a permanent presence on site. It then takes some time for the police patrol to arrive on site.

That varies from country to country. In Italy, the public prosecutor is immediately informed of criminal activity through the police forces that we have on our premises. It is then up to the state to decide how and in what form to proceed.

It really depends on the damage inflicted. There is the offense of ‘disruption of public service.’ In Italy, museums are considered a so-called ‘primary service’ and are therefore on par with hospitals, schools, etc. Accordingly, there are corresponding penalties. However, there are different approaches. At the moment when damage occurs, or—let’s hope it doesn’t happen—there is even destruction of a cultural asset, the museum could also act as a private plaintiff on that occasion. This has not happened yet, but such an offense will definitely be regulated by criminal law too. The penalties for damaging public cultural property in Italy were very low for many years; they were raised only two years ago, but they are not yet where they need to be to effectively prevent such damage.

In case of damage to an artwork, which already existed in the past when someone spray-painted a house wall, for example, private law often makes up the bulk of the claim for damages. In such cases, the criminal aspect was often penalized by only a few hundred euros up till now. In the meantime, however, this amount has been raised, so it remains to be seen whether this is adequate or whether it should be raised even further. However, since this increase is still relatively new, we have not yet gained enough data to make a final assessment.

I would say that the problem is not so much that certain problems cannot be addressed—even quite controversially—in discourse, in a conversation—but that the rules that generally apply to dialogue must apply, whether in school, in parliament, or in public discussion. It is often claimed that these actions are completely free of violence, but this is not the case. There is verbal violence, there is simulated, theatrical violence against works of art, and that is violence, too. Museums may be a social space of encounter, a very open space, in which everyone can read a work of art in relation to his or her own personal situation—which could definitely be a political situation, but also in relation to higher values, because we have a lot of religious art in our European museums. Ours must be a space that is fundamentally a ‘safe space,’ a space free of violence. If certain people introduce violence in a certain form, then this whole communication space is violated and disturbed.