The UN’s special rapporteurs are all appointed by the Human Rights Council, and the people who are chosen are those whose main interest is to condemn the West, colonialism, and capitalism.

What is history but a fable agreed upon?

–Napoleon Bonaparte

There is a thin line between history and fiction, and awareness of this, while not limited to dictators, is certainly one of their many tools of control. Recently, there’s been a lot of buzz about the cultural origins of Ukraine. Is there any merit to Russia’s claim to Ukraine as historically invested? This past summer, the President of Russia Valdimir Putin issued a statement regarding Russian-Ukrainian relations, recollecting their shared historical past: “Russians and Ukrainians were one people—a single whole,” words that frame Putin’s claim on Ukraine as organic, as a return to an ideal past. Putin defended his words by writing a sweeping history of the intersectionality of their peoples, spanning over a thousand years beginning with the baptism of Rus’ and ending with Ukraine’s entanglement with NATO. The core of his message throughout the twenty-page account is that the two countries belong together:

Our spiritual, human and civilizational ties formed for centuries and have their origins in the same sources, they have been hardened by common trials, achievements and victories. Our kinship has been transmitted from generation to generation. It is in the hearts and the memory of people living in modern Russia and Ukraine, in the blood ties that unite millions of our families. Together we have always been and will be many times stronger and more successful. For we are one people. … Russia has never been and will never be “anti-Ukraine.” And what Ukraine will be—it is up to its citizens to decide.

It’s a nice dream, a fable, this artful arrangement of history to respond to the question of national identity and thereby justify Russia’s claims to Ukraine.

But there is more to the story. In an effort to better understand Ukrainian and Russian history, Gergő Kovács of the Hungarian news magazine Mandiner interviewed Dr. Csilla Fedinec, historian, editor, senior research fellow at the Budapest-based Research Centre for Social Sciences. Here she takes questions on Ukrainian identity, Russian-Ukraine relationship development, and the possibility for a historical reason behind the current war.

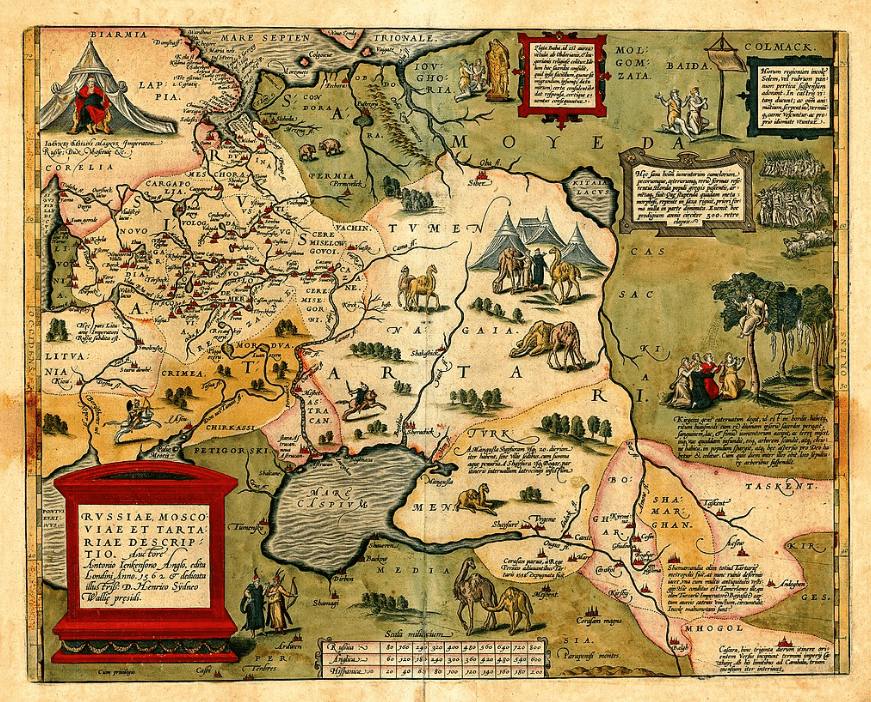

In the age of the Kyivan Rus, there were neither Ukrainians nor Russians. The population was heterogeneous, comprising the tribes of Polans, Severians, Ulichians, Teverians, Drevlyans, Dregovichians, Krivichians, Radimichians, Slovenians, and White Croats. The political formation called ‘Kyivan Rus’ emerged from these ethnic groups. The original homeland of Slavic peoples was to the north of the Carpathian Mountains, between the Vistula and Dnieper Rivers, where they began their eastward migration in the 6th and 7th centuries. Slavic peoples who had been living on the Eastern European steppe came into contact, as they moved eastward, with armed groups of Varangian (that is, Viking) merchants, who had a strong impact on the setup of the state organisation called the Kyivan Rus.

Mongolian conquerors migrating from Asia at the turn of the 1230s and 1240s attacked the principalities of the Kyivan Rus one after the other, physically occupying their core areas, including Kyiv, and then establishing their vast state, the Golden Horde. The unoccupied western periphery, which followed the traditions of the Rus, was gradually falling under Polish-Lithuanian rule, while the north-eastern parts became a vassal of the Mongols. Following the disintegration of the Golden Horde, 1480s, the Grand Prince of Moscow managed to shake off the guardianship of one of its rump states, the Great Horde, with the assistance of another one, the Crimean Khanate, a conquest that played a decisive role in laying the foundations of the Russian Empire by Moscow. To put the history of these two countries in perspective, Moscow was still very much a swamp when Kyiv was founded.

The changes that came after the founding of Moscow, in the twelfth century, had a major economic, linguistic, and cultural effect on the former Eastern Slavic population, and eventually it splintered—Ukrainians, Belarusians, and Russians became separate entities. It is an interesting fact that the people’s name ‘Ukrainian’ is a relatively late development: it only came into use in the 19th century. Previously, the words Ruthenian (Latin) and Rusyn (Slavic), derived from ‘Rus,’ were used for self-identification. Thus, the Kyivan Rus had three successors both ethnically and territorially speaking, similarly to Charlemagne’s empire.

The Cossacks were an important element in the ethno-genesis of Ukrainians. They were serfs, fleeing Polish and Russian feudal landlords, who first appeared en masse in the uninhabited southern territories of the Eastern European steppe in the 15th century. They organised themselves into free communities, based on military order, primarily for protection against external enemies, and they formed a natural bulwark against Turkish-Tartar onslaught, for the Polish-Lithuanian and Russian states. Within two hundred years, these communities found themselves at the centre of regional disputes with their neighbours.

The part of the Cossacks annexed by the Polish-Lithuanian state commenced a major struggle for freedom in the middle of the 17th century, independently at first, and subsequently seeking external allies. They sought help from Moscow. As a result of their alliance with Moscow, they came under Russian rule. Cossacks understood Moscow’s support as a kind of protectorate, but Moscow interpreted their signing of the Pereyaslav Agreement of 1654 as submission, and, promising them freedom initially, then autonomy, it fully abolished ‘Ukrainian separateness’ by the end of the 18th century, simultaneously occupying and eliminating the Crimean Khanate, turning the peninsula into a strategic base. The process of settling the Russian population there began, and it continued during the Soviet era. At the end of the Second World War, in an effort to purge the population, Stalin deported Crimean Tatars stamping them ‘collectively guilty,’ and their gradual resettlement only became possible at the end of the 1980s.

They did, indeed, but the 19th century was also determined to push back Ukrainian national awareness and the Ukrainian language in Russia. The situation was slightly more advantageous in the territory which is called Western Ukraine today, the areas annexed by the Austrian Empire, during the cutting up of Rzeczpospolita, the Polish-Lithuanian confederation. After the Austro-Hungarian Compromise of 1867, Emperor Franz Joseph adopted a slow liberalisation policy in respect to the nationalities, and Galicia, the region of eastern Ukraine and western Poland, became a de facto autonomous province of the crown as of 1873.

The next chance for Ukrainians came after the 1917 revolutions in Russia, when, like other national movements on the periphery, two Ukrainian entities tried to organise themselves: the Ukrainian People’s Republic, and the Western Ukrainian People’s Republic. Bolshevik expansion, however, rendered these attempts futile.The Bolsheviks proclaimed the Ukrainian Soviet Republic, set its capital in Kharkiv, subsequently integrating all Ukrainian areas in it. Until the middle of the 1930s, the capital was Kharkiv, and not Kyiv.

During the Soviet era, after the 1920s which was a permissive period from the perspective of nationalities, the Ukrainian language was artificially pulled closer to Russian in terms of both vocabulary and spelling. Earlier, the Poles (in Western Ukraine) and Tsarist Russia were content with exerting external pressure on the Ukrainian language by prohibiting or restricting its use. The Soviet regime, however, used conventional tools of language policy and interfered in the development of the language. While the Soviet Union existed, it was obvious that linguistic assimilation was the most effective tool of integration of its peoples.

After 1991, this process was reversed in independent Ukraine, and it is not true anymore that you understand Ukrainian if you speak Russian. Today, they are related but clearly distinct languages. It is different in the case of Belarusians, who hardly use their mother tongue any longer, and their country is a ‘vassal’ state. Ukraine wanted to avoid a similarly crushing brotherly hug.

First, it should be noted that in the Soviet era, not only were the borders of Ukraine drawn, but those of the rest of the Soviet republics too, including the Russian one, and each gained their independence with those borders when the Soviet Union broke up in 1991. Obviously, in the current situation, the Russian-Ukrainian border is of interest. Debates regarding the internal borders of Ukraine, one of the founding republics of the Soviet Union in 1922 set up by force by the Bolsheviks, continued for a number of years afterwards.

The territory of Ukraine was a lot bigger towards the east than it is currently; in 1928 when the debates on this section of the border were concluded, Ukraine lost extensive areas, but the industrial Donbas region remained within its border. The justification offered by Stalin, the People’s Commissar of Nationalities, was that they wanted to increase the ratio of the proletariat, that is, the social basis of Bolshevism, within Ukraine.

Lenin’s concept of the establishment of a federation of republics with equal rights was implemented, rather than Stalin’s idea of having the territories of the Nationalities join Russia. Subsequently, Stalin was able to find another way to approach his original vision by gradually taking rights away from the republics, thereby completing the centralization of the country. Apart from the establishment of a federation, however, Lenin’s vision was rarely implemented at all. Instead, each Soviet leader strove to mould Leninism as they pleased. Lenin’s works were published and often quoted (at times with favour and other times with derision) throughout the Soviet era. This is how Leninism managed to stay ‘relevant’ at all times.

Stalin’s idea was for the national territories to join Russia with autonomous status, but it was Lenin’s concept that a federation of republics with equal rights should be created that eventually came to fruition. Later, Stalin came closer to his own vision by gradually disenfranchising the republics, thereby achieving the complete centralisation of the country. Beyond the establishment of a federation, however, Leninist principles were rarely implemented. Instead, each Soviet leader strove to mould Leninism as they pleased.Lenin’s works were published and often quoted (at times with favour and other times with derision) throughout the Soviet era. This is how Leninism managed to stay ‘relevant’ at all times.

After World War II, proclaiming the ‘greatness of the Russian people’ became commonplace, while members of a number of minor nationalities were deported en masse. In 1956, at the 20th Congress of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, Nikita Khrushchev stated that Stalin decided not to displace the Ukrainian people for the single reason that there were ‘too many of them.’

The truth is, all three Soviet constitutions (1924, 1936, and 1977) stipulated the principle of secession (free exit) for each member republic, but it remained unrealistic until 1991. The disintegration of the Soviet Union was caused by the economic crisis, and only to a lesser extent by nationalism. The process was not followed by a bloodbath, unlike in the case of Yugoslavia, but it left frozen conflict zones, territorial entities not recognized by international law which have continued to exist to this day, including Transnistria (Moldova), South-Ossetia, Abkhazia (Georgia), and Nagorno Karabakh (Azerbaijan).

With the exception of current Ukraine, no independent Ukrainian state had existed historically, but the Ukrainian people growing in numbers to tens of millions over the centuries have had their role in history as an important factor to reckon with by the empires controlling the territories populated by them, and they undoubtedly had a sense of unity throughout their history—and, since the age of nationalism in Europe, a coherent national awareness as well.

I think it would be out-of-place and improper in this situation to look, hypocritically, for historical causes. The “historical” angle was brought up by Russian president Putin in relation to the current crisis, to question, on that basis, the raison d’être of the Ukrainian state and the very existence of the Ukrainian nation. This war, the taking of human lives, cannot be justified by anything. This is a major catastrophe for Ukraine, and the entire globe. It will bring down the iron curtain again, with unforeseeable consequences. This tragedy has proven that Ukraine was right to fear what they foresaw as inevitable, sending the message to the world continuously since 2014: Russia will stop at nothing.