France and Germany are celebrating sixty years of the Élysée Treaty, signed on January 22nd, 1963 between General de Gaulle and Chancellor Konrad Adenauer. This anniversary comes at a time when relations between the two countries, now represented by President Emmanuel Macron and Chancellor Olaf Scholz, are more than tense.

The German chancellor was in Paris on Sunday, January 22nd, to try to reinvigorate a pairing that is supposed to be the driving force of the European Union, but whose disagreements have been particularly significant in recent months. In October, the annual meeting of the Franco-German Council of Ministers had to be canceled due to persistent tensions between the two governments: Germany had just put in place a €200 billion energy aid plan for its industry and households without informing France and other European partners. After being canceled in October, the council was eventually held on Sunday at the Elysée Palace after a commemorative ceremony at the Sorbonne University.

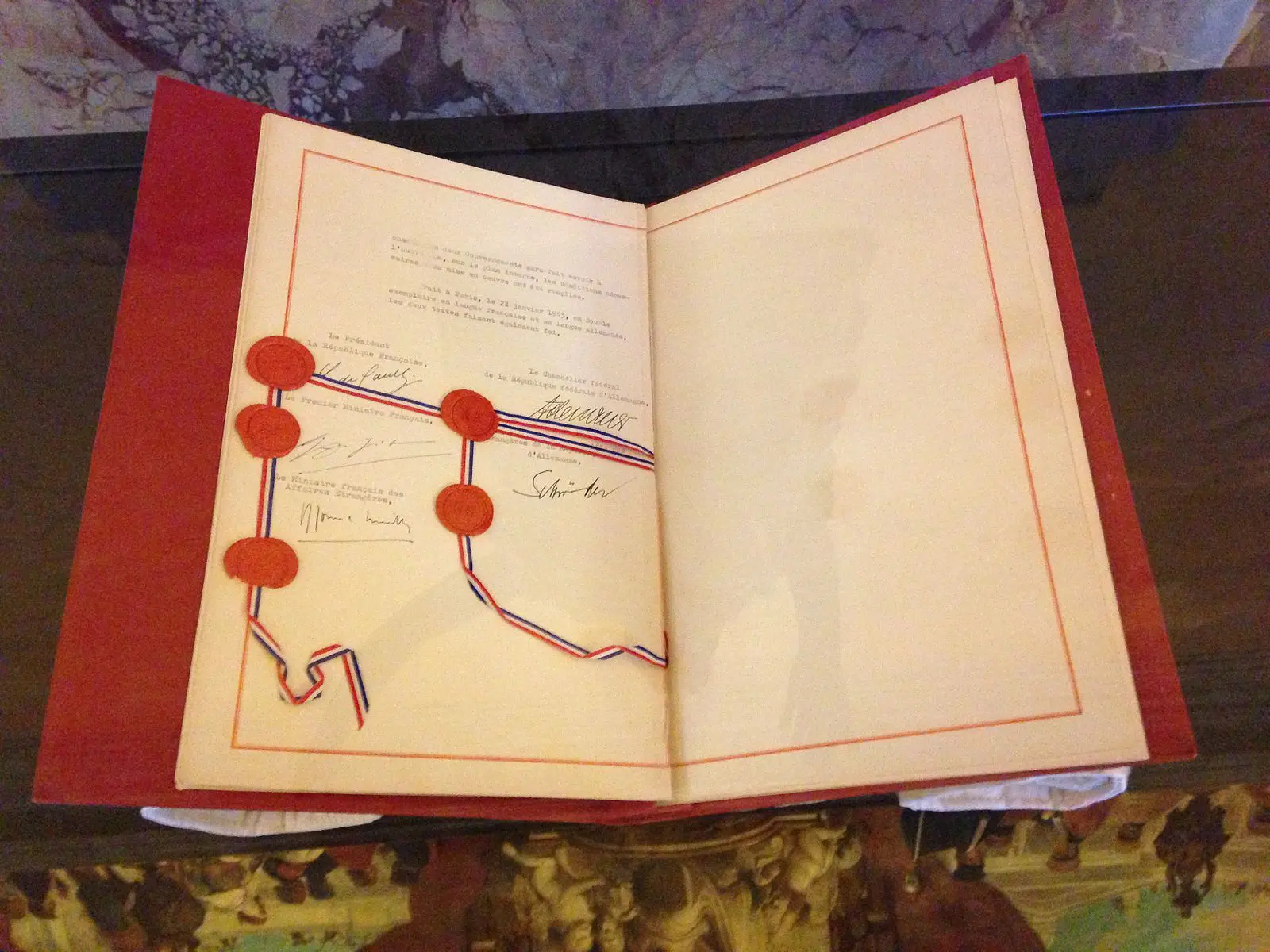

A joint article signed by the two leaders appeared simultaneously in the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung and the Journal du Dimanche on January 20th. It paid tribute to the commitment made by their predecessors de Gaulle and Adenauer in a Europe that wished to turn the page on the tragedy of the two world wars, and which still obliges them today, while war rages in the East. At the time, the text, written in French and German, aimed to strengthen cooperation between the two countries in the fields of diplomacy, defense, and education. Continuing to build on this founding text, Olaf Scholz and Emmanuel Macron have affirmed their desire for “Europe to become even more sovereign” by investing more in defense and by adopting “a strategy for strengthening European industrial competitiveness.” The two countries agree on the need for action but are debating how to go about it.

France hopes to draw Germany’s attention to the risk of deindustrialization in Europe as a result of the anti-inflation measures implemented in the United States, which strongly favor American industries to the detriment of European companies. German industry, with its stronger backbone, does not seem to be moved by this to the same extent as its French counterpart.

Another stumbling block is Germany’s defense investment policy. Germany, which is rearming, has chosen to favor American rather than European equipment and has launched a project for an anti-missile shield bringing together fourteen European countries, in cooperation with Israel and the United States, but without France. Only the Franco-German FCAS (Future Combat Air System, or SCAF in French, for Système de combat aérien du futur) project is progressing, but slowly, with a contract signed in December to enter a new phase of the project.

Chancellor Olaf Scholz has emphasized his desire to see the Franco-German ‘couple’ return to being a “locomotive” for Europe, and hopes to see divergences transformed into strength in what he calls a “compromise machine” allowing “controversies and divergent interests to be transformed into convergent action.” The term ‘couple’ is being abandoned by the official communication of the two countries, which considers its connotation too emotional, in favor of the more neutral ‘tandem,’ which emphasizes the necessary synchronization of the two partners.

With the official ceremonies, harmony seems to have been temporarily restored—but no one knows for how long.