In what marks a major shift in its energy policy, Belgium will continue drawing on nuclear power. Citing a “chaotic geopolitical context,” brought about by the Ukraine war, the government announced on Friday it will now make independence from fossil fuels its top priority.

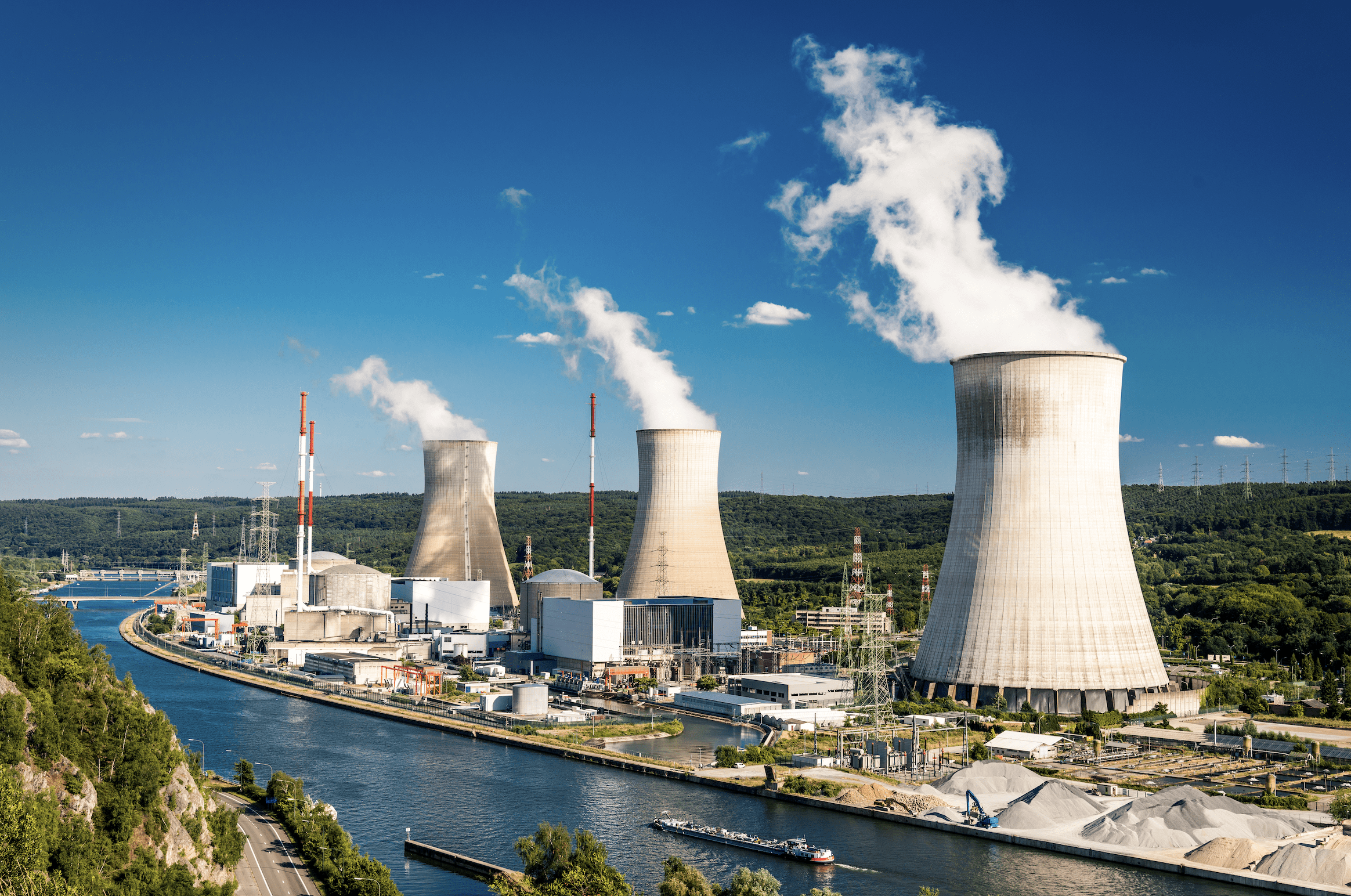

To secure that independence, the government wants the Doel 4 and Tihange 3 nuclear power plants—the country’s youngest—to remain operational for another ten years. Amidst exploding electricity bills and fears over shortages, the 180-degree turn came not entirely unexpected. Such pressing circumstances left Belgium’s Vivaldi coalition—named after composer Vivaldi’s The Four Seasons, and made up of the liberals (Open Vld and MR), the socialists (Vooruit and PS), the greens (Groen and Ecolo) and the Christian democrats (CD&V)—with little choice.

Additionally, it allows for the government to expedite the switch to renewable energies. To that end, it is allocating €1.1 billion extra to investments in offshore wind power, solar energy, and hydrogen. The government views the latter as “one of the main clean energy sources of the future.” Therefore, “new efforts” will be made to accelerate the transition which would make Belgium a “hub for the import and transit of green hydrogen.” Companies will be encouraged to make the switch. It has also agreed that energy derived from nuclear power must not “crowd out” renewable electricity. In the event of overproduction, nuclear power plants can therefore be used to launch the hydrogen market.

The government reaffirmed its interest in small modular nuclear reactors as well. Aided by its “cutting-edge expertise” in the field of new nuclear technologies, it said it will invest €25 million a year in this field for the next four years.

Plans for a nuclear exit go back to 2003, and have remained controversial ever since. Spearheaded by the federal government’s Green parties, these would have brought about independence from nuclear power by 2025, and seemed on track to meet that deadline. Contingent on these plans was the hope that gas plants would furnish the short-term energy demands needed after the nuclear exit. The West’s soured relationship with Russia, an important gas supplier, has now made that scenario impractical.

In what struck critics as a contradictory move, Prime Minister Alexander De Croo (Open Vld) and his team gave the go-ahead for the construction of two gas plants. These would serve as buffers should nuclear power be unable to furnish the energy needed. Speaking at a press conference on Friday, Prime Minister Alexander De Croo stressed that this combination would guarantee energy supply “in all scenarios.”

While Russia’s gas exports to Belgium are slim (Belgium receives only 4- 6% of its gas from Russia), the fact that Belgium is part of the EU gas market (which is reliant on Russia for 40% of its gas), means that shortages and price fluctuations will also hit home there. Belgium however does possess a large LNG (Liquified Natural Gas) terminal in the port of Zeebrugge. This could offer flexibility in case the EU needs to import more gas from the U.S. or other sources.

The decision has left some baffled. Walloon majority party Mouvement Réformateur (MR) and Flemish opposition party Nieuw-Vlaamse Alliantie (N-VA) have been most vocal. They are relieved by this re-embrace of nuclear energy, but criticize the government over its recourse to gas. They deem it absurd that the two nuclear power plants are being kept open for only ten years, while others are being left unused, and that instead, two additional gas plants are being built. This, they say, flouts Europe’s intention to wean itself off Russian gas. They worry about energy scarcity and that neighboring countries will not be able to fill the vacuum.

MR party chairman Georges-Louis Bouche tweeted on Friday that the “only credible energy mix consists of nuclear and renewable energy,” and that “there is still a lot of work to do. We will continue to fight for our country!”

De enige geloofwaardige energiemix bestaat uit kernenergie en hernieuwbare energie. Als iedereen binnen de termijnen had gewerkt, zouden de zaken beter verlopen kunnen zijn. Er is nog veel werk. We zullen voor ons land blijven vechten! #trotseliberaal 🇧🇪 pic.twitter.com/Ub5r6V6Ako

— Georges-L BOUCHEZ (@GLBouchez) March 18, 2022

Further pursuing the matter, party chairman to the N-VA, Bart De Wever spoke to VTM Nieuws on Sunday. There he said that “[Russian President Vladimir] Putin has made it clear that electricity is best generated in one’s own country,” and that if that is not the case, you “become dependent on the price manipulations that a single man can bring about.” He added that every end of the month, “people see what these green policies have produced. It has become way too expensive.”

He went on to question Minister of Energy Tinne Van der Straeten’s (Groen) dealings with Engie, the French energy company which manages Doel 4 and Tihange 3, and which will also operate the new gas plants. For the latter, it will receive subsidies. De Wever argued that the numbers don’t add up and that, in light of valid alternatives, construction of these is wholly unnecessary. Accusing Van der Straeten of “lying” and being gripped by “dogmatism,” De Wever cast doubt on the wisdom of allowing her to be the government’s negotiator with the company.

It is expected that, should a new agreement with Engie be reached, this will come with a hefty price tag. Groen’s chairman, Meyrem Almaci (who on Wednesday abruptly resigned), said that “no blank check” will be given however, and that additional burdens will not be imposed on taxpayers. Minister Van der Straeten stressed that there will be no change in the set of responsibilities for Engie, such as the storing of nuclear waste, which costs billions. Prime Minister De Croo made known that there had been “a lot of contact” with the company in recent weeks, and that his government would “negotiate with them in a respectful way;” conduct he was sure they would reciprocate.

Meanwhile, Minister of Energy Tinne Van der Straeten seeks to paint the draft bill as a victory since it includes significant investment in renewables. The Greens have lost precious political capital however, and are experiencing pushback from their base. If not being able to deliver on the much-sought farewell to nuclear power did not cause consternation, investment in Co2-emitting gas plants surely will. Groen’s German colleagues, whose government has gone all-in on zero nuclear energy, are equally displeased. In a separate tweet, German Minister of the Environment Steffi Lemke (Greens) is said to “regret Belgium’s decision,” and promises that “in view of safety, economic and legal risks,” she and her party rule out such extensions for Germany.

The draft bill relating to the power plants’ extension will be submitted by the end of March, and is expected to be formally approved by the Council of Ministers.