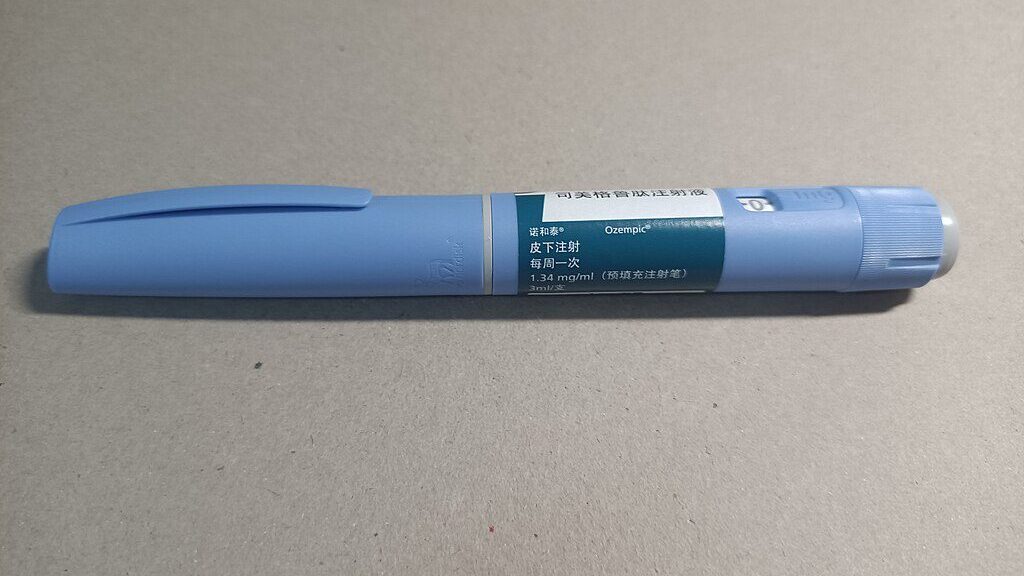

Ozempic injection pen

Photo: HualinXMN, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Prime minister Sir Keir Starmer and his health secretary Wes Streeting argue that medication could play a key role in UK economic growth, by helping obese people return to work.

Announcing a £279 million investment from pharmaceutical giant Lilly, the leading Labour figures looked forward to improving healthcare, including with a five-year mass study—i.e., one much larger than a clinical trial applied in daily life—to see if an effective obesity treatment can be applied across the Greater Manchester region, possibly prior to a national roll-out.

The ‘weight-loss jab’, according to Starmer, is

very important for our NHS, because, yes we need more money for the NHS, but we’ve also got to think differently.

The wonder drug in question is semaglutide, better known under such brand names as Rybelsus, Ozempic (initially used to treat diabetes), and the higher-dose version Wegovy, marketed to encourage weight loss.

Even given the potential of such pharmaceutical breakthroughs, Streeting and Starmer have jumped the gun—if not the shark—in their enthusiasm. Part of a government that complains it inherited a £22m ‘black hole’ from its Tory predecessor, Streeting estimates that obesity-related illnesses cost the state-funded National Health Service £11bn (€13.2bn) a year. Not only would medicating the obese cut the deficit, he seems to think, but it would also boost productivity by readmitting those receiving the treatment to the workforce.

On productivity, Starmer assumes that well-paying jobs are there waiting to open up to the newly medicated and slimmed down. On public health, his sidekick Streeting errs in seeing populations as treatable in the same way that a careful doctor-patient relationship can help the sick, including the obese.

Semaglutide works by suppressing the appetite, thus encouraging cutting calorie consumption. It has already attracted puritanical-sounding criticism because the promise of convenient weight loss without an intensive dietary or exercise regime seemed too ‘easy’ and ‘unnatural’ for some observers. Despite a recent shift to ‘body positive’ ideology, British public opinion remains divided over whether obesity is a health problem or a question of behaviour and (bad) choices.

Since the Blair years, Labour has shown a commitment to ‘reforming’ individual lifestyles—’helping people to make the right choices,’ in the jargon—and importing/incorporating the strategy of behavioural ‘nudge’ into government policy. Objectors who saw this as evidence of the ‘nanny state’ in action are now routinely treated as a problem. For instance, former ‘Conservative’ health minister, Lord Bethell welcomed the policy, declaring

People want help from government—the ‘nanny state’ thing was a distraction.

Insofar as excess weight is inconvenient and potentially damaging to health, Bethell has a point. Yet the vague terms on which this policy is being floated reveal its underlying weakness. The British adults falling within its scope can be characterised as overweight, obese and morbidly obese (now renamed Class III obesity, with a body mass index of 40 or higher, or a BMI of 35-39 coupled with obesity-related health conditions). Setting aside the problems of using BMI as a measurement, it is being in the last of these three categories that is likely to prevent normal employment.

A key weakness with turning the current medical advances into policy is that after two years, the advice is to stop taking semaglutide. Without that pharma-induced feeling of being ‘full,’ an appetite will return—and with it, almost inevitably, weight gain.

Does this mean that employees who regain weight are destined once again for the dole queue? Maybe; more certain is that Labour’s now-traditional emphasis on policing lifestyle and behaviour will find ways to scapegoat them for a policy that is set up to fail.