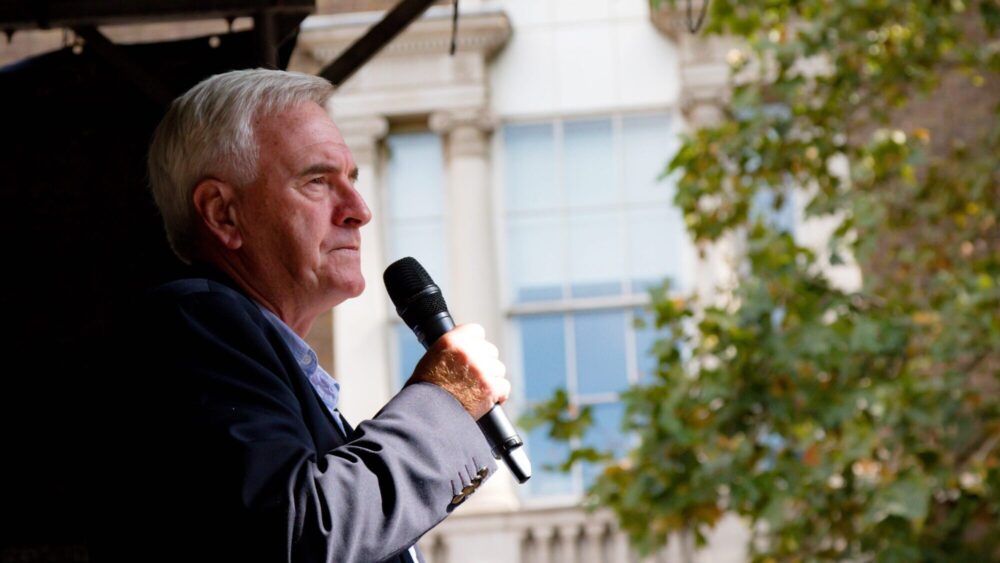

John McDonnell

Photo: Ben Gingell / Shutterstock.com

Sir Keir Starmer’s Labour Conference speech, likely his last before the next election, was fairly standard in that it did not reveal much in the way of actual policy. But the more left-wing elements of his party are already gearing up to ensure that a Labour government would be a “radical” one.

One now-fringe voice has received particular attention—that of John McDonnell. McDonnell served under former leader Jeremy Corbyn, whose influence the party is trying to subdue, as shadow chancellor. In 2006, he said his “most significant intellectual” influences were the “fundamental Marxist [writings] of Marx, Lenin, and Trotsky, basically,” and while talking from Labour’s front bench in 2015, he read from Chairman Mao’s Little Red Book. McDonnell is now gearing up opposition activists to “change the [Labour] agenda” should the party gain power next year.

Talking at a conference event on Tuesday, McDonnell, quoted in The Daily Telegraph, said:

At the moment, Labour is saying little about detail, and I do understand that: the reservations, the Ming vase argument, don’t want to drop it or whatever. I can understand it to a certain extent. I don’t agree with it, but I can understand it. So even if they’re not saying much specifically before the election and the manifesto might be lightweight, I think in that first year [of a possible Labour government], that’s our opportunity to change the agenda ….

And so our job, I think, is to make sure two things: one, that we have the radical proposals that we want implemented on the shelf and ready to go, to hit the deck running; and the second, is maintaining an alliance with others … that will enable us to influence that government when it goes into office. So I think at that stage, all opportunities take place.

He pointed in particular to the need for a “much more radical approach to the way Labour will develop education in this country.” McDonnell holds the view, typical of Labour Party activists, that university tuition fees should be scrapped, despite half of Britain’s young choosing, or being pushed down, this path.

Despite being thin on substance, some argue that Labour’s stance is radical enough as it stands. The Financial Times earlier this year commented that the party’s “radical” programme would “leave the UK economy looking very different,” for better and for worse. At around the same time, Labour activists insisted that the buildup to the next election was not the time for the party to be “timid” or for its socialist faction to be “silent” on matters such as wealth redistribution.

But most of these debates revolve around economics. Much less is said about an upcoming Labour government’s “radical” social programme, perhaps because its distinction from that of the Tories is negligible.