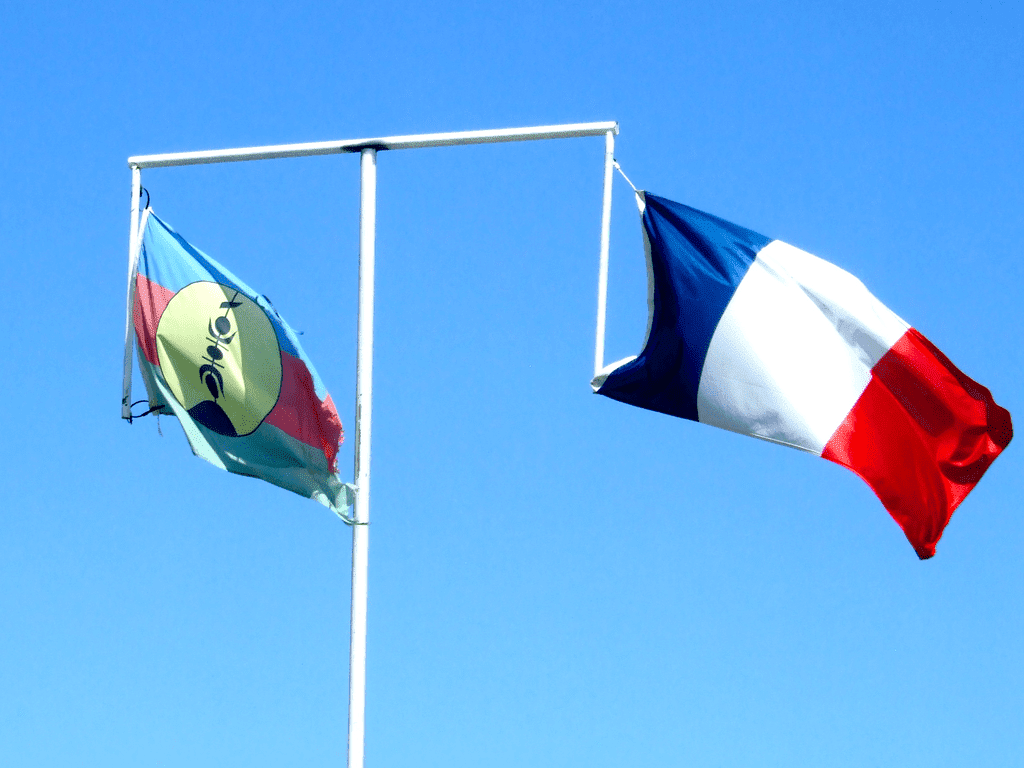

Does France Want to “Decolonize” New Caledonia?

On December 12th, the third referendum in New Caledonia will be held to decide if this French territory in the Pacific Ocean will become an independent state.

Nearly 23 years ago, on 5 May 1998, former Prime Minister Lionel Jospin had the Nouméa Accords drawn up and signed, providing for a generalized transfer of powers to New Caledonia through the organization of popular consultations on the subject of self-determination of the Caledonian islands. During his own presidency, Emmanuel Macron has pursued the policy inaugurated by the Nouméa Accords. Two referendums have already been held, in 2018 and 2020. The question to be asked on December 12th is unambiguous: “Do you want New Caledonia to accede to full sovereignty and become independent?”

Twice, the question had been put to Kanaks and French people living on the island (excluding those who moved there after 1994). And twice, the result was clear-cut in favour of remaining in France, with a participation rate of 85%. But that is not enough, and those in favour of independence want to force people to vote again to achieve their goal. The process is not new; the European Union, for example, is accustomed to having people vote repeatedly until it obtains the results it wants.

So far, President Macron has been in favour of keeping New Caledonia as a French territory. And for good reason: in addition to the well-known and highly desirable nickel reserves, the Pacific archipelago provides an exclusive economic zone of 1,740,000 km² that would disappear with independence. There is speculation that Macron agreed to swallow the bitter pill of the Australian submarine contract cancellation in exchange for U.S.-Australian support for maintaining the French presence in New Caledonia.

A Special Committee on Decolonization within the United Nations is closely monitoring the situation. This is no coincidence as the UN has a history of meddling in French territorial claims, as demonstrated back in the 1960s with regard to France’s North African provinces. But that’s not all. The crises linked to the pandemic have reshuffled the cards. In the West Indies, Martinique is rebelling and Guadeloupe is on fire against the health policy of the French government. The Minister for Overseas Territories Sébastien Lecornu has therefore taken the opportunity to put the question of New Caledonia’s autonomy on the table—indifferent to the fact that French presence there dates back to the 17th century.

As it waits for the referendum, New Caledonia still depends on metropolitan France for 30% of its public revenue. How can it seriously consider independence under such conditions? Most Caledonians are well aware of their economic dependence on France. However, some Kanak citizens, a loud minority, have tried to delay the referendum, blaming the pandemic, but the Council of State refuses to change the date. They don’t want to participate in the vote because they know the vote will not end in their favour. Nor do they want to recognize the vote of the French population who have been living in New Caledonia for decades. Will the ‘independents’ try to impose a 4th referendum to achieve their goal? They have already announced that they will not accept the results and will call for the United Nations to intervene on their behalf..