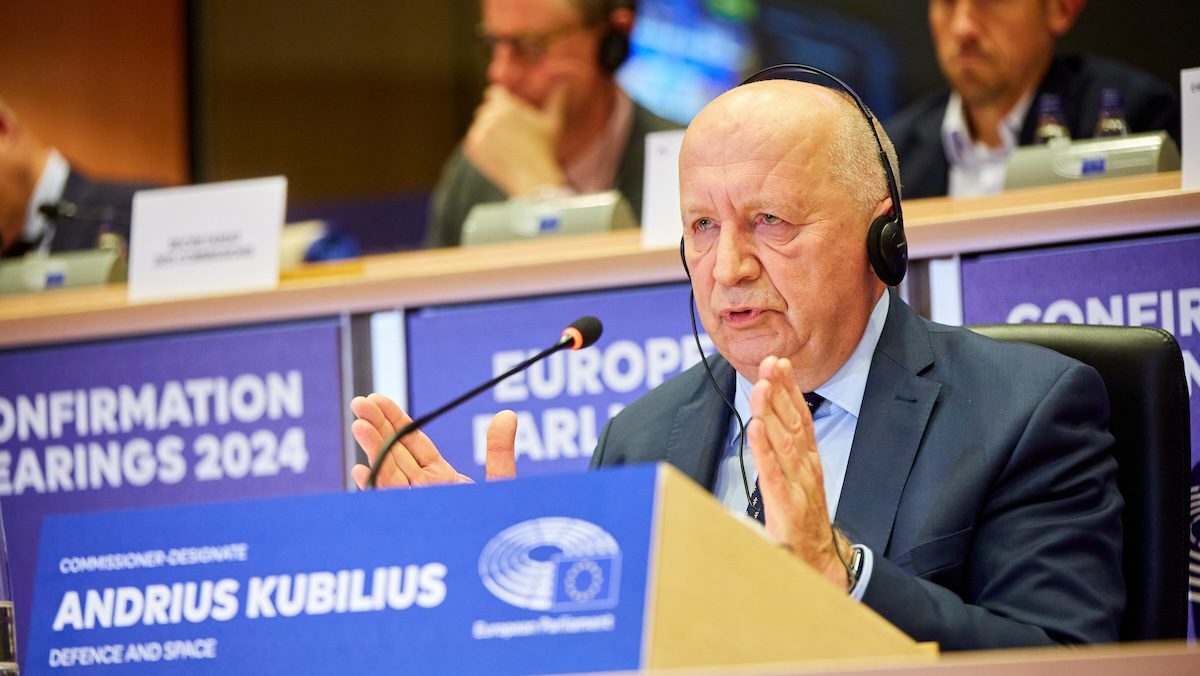

EU Defense and Space Commissioner Andrius Kubilius.

Photo: Bogdan Hoyaux © European Union, 2024—Source: EC – Audiovisual Service

In his first interview with Politico after becoming the EU’s first-ever Defense and Space Commissioner, Andrius Kubilius called for the bloc’s next seven-year budget to include close to €100 billion allocated solely to defense.

In comparison, the current €1 trillion EU budget has only €10 billion for defense, so Kubilius is calling for a ten-fold increase after 2027.

“We need to be ready for the possibility of Russian aggression,” said Kubilius, a two-time prime minister of Lithuania who’s known for being hawkish on Russia. “If we fail in Ukraine, then of course, the possibility of Russian military aggression against the EU member states can increase.”

For a long time, defense used to be viewed as one of those things that Brussels shouldn’t have too big of a hand in. But as with many other things, the war in Ukraine has since overwritten this standpoint.

Kubilius’ portfolio was created specifically for the second von der Leyen Commission to oversee the integration of Europe’s fragmented defense industry, bolster manufacturing and defense spending, facilitate increased military aid to Ukraine, and improve military cooperation within NATO.

But all this, of course, requires a lot of money, especially given that most European countries were seriously lagging in terms of defense investments before the war and only a handful of them were taking NATO’s 2% defense spending rule seriously. Two-thirds of them have reached that threshold since, but that doesn’t mean they can lean back and celebrate because analysts predict that NATO will gradually raise the requirement to 3% or more in the coming years as global tensions intensify.

Filling the EU’s €100 billion war chest will be difficult, to say the least. It would require massively increasing the bloc’s common budget, issuing more joint debt, or easing European Investment Bank rules around arms manufacturing investments—or, most likely, a combination of all of these.

Kubilius also said defense spending should be excluded from deficit calculations. The current fiscal rules in the EU punish countries for running budget deficits of over 3% or having a public debt of more than 60% of the GDP. Kubilius, however, would rather let countries like Greece, Italy, or Poland go into more debt than hinder spending enough on their defense.

“When you are facing a crisis, you need to look at how you can have some kind of flexibility in spending on some specific issues,” he said, adding that he has already pitched his idea to Budget Commissioner Piotr Serafin, a Pole who understands that “defense is really a priority.”

The new defense chief also talked about the EU’s new €1.5 billion industry-boosting program (EDIP), which is meant to ramp up both domestic arms production and the amount of weapons EU countries buy from each other as opposed to overseas.

The problem is that the Council is still squabbling over the details: countries with established arms manufacturing bases want a strict ‘Buy European’ clause tied to joint investments, while others, like Poland, want to buy as many weapons as possible in a short time, meaning a continued reliance on U.S.-made arms.

Kubilius made it clear he favored the second camp, arguing that protectionism is not the way forward in the current geopolitical crisis.

“Definitely, we shall need to procure from the United States or from other partners,” he said. “When we are saying we are buying European, that does not mean that we shall not go around to look for some kind of weapons which we simply are not producing or producing in too small quantities.”

As to what Europe’s spending priorities should be, Kubilius pointed to NATO’s upcoming report on capability gaps as the EU’s operation guide, which will call for 49 new brigades, 1,500 tanks, and 1,000 artillery pieces.

Europe needs to be ready for war, he said. The “axis of authoritarian countries” as in Russia, North Korea, Iran, and somewhat China are “uniting themselves, and we need to unite ourselves.”