Shiite Muslim clerics chant slogans during an anti-Israel rally in solidarity with the Palestinian people organised by supporters of the Lebanese Shiite movement Hezbollah in Lebanon’s southern city of Nabatieh on October 13, 2023.

Photo: MAHMOUD ZAYYAT / AFP

The war between Israel and the Hamas terror organisation in Gaza is quickly making its effect felt across the Middle East, threatening to escalate and expand the conflict, and alter the geopolitical state of play in the region.

Both Reuters and AFP reported in the past few days that Saudi Arabia is intending to halt the process of normalising its ties with the United States and Israel, as a direct result of Hamas’s massacre in Israel, and Israel’s retaliatory attack on Gaza.

As one of the most powerful and wealthiest countries in the Arabic-speaking Muslim world, home to Islam’s holiest sites, Saudi Arabia cannot be seen as a nation that tolerates an attack—even a provoked one—on Palestinian Arabs. “When there is a major Palestinian crisis, it becomes impossible for the leadership of Saudi Arabia to publicly break ranks from the Islamic and Arabic camp”, according to an analysis in Time magazine.

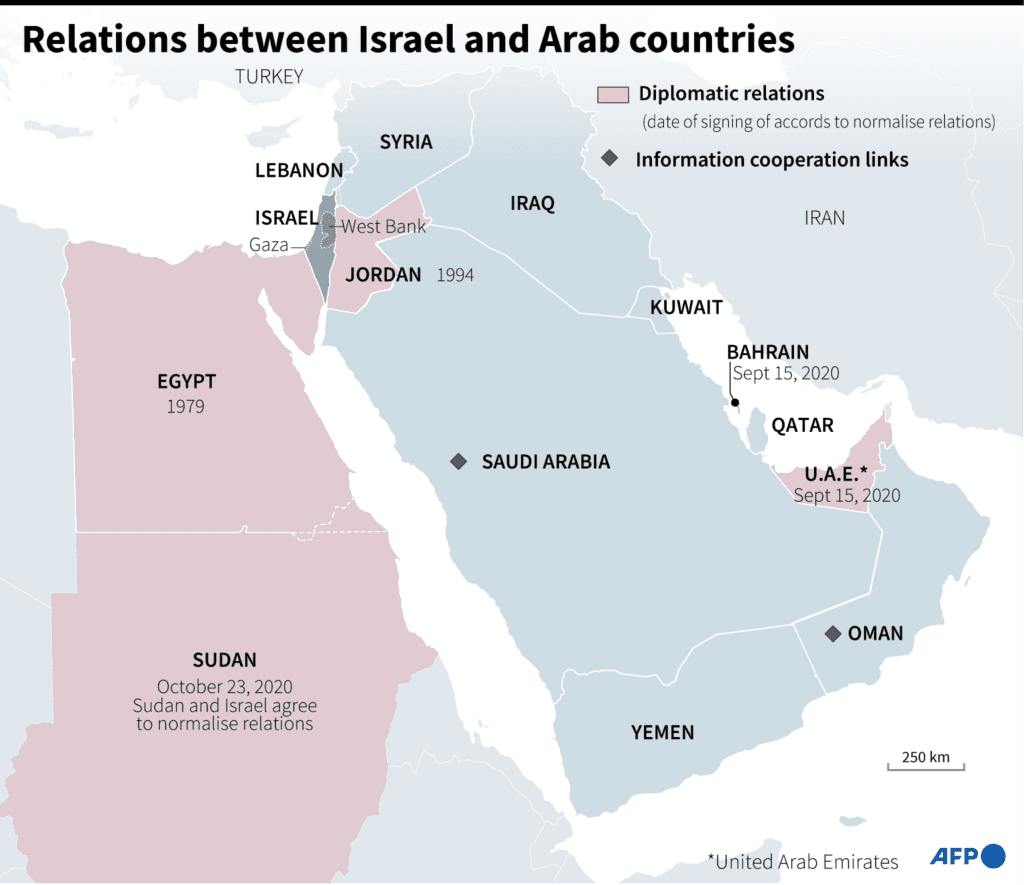

Saudi Arabia and Israel have never had formal diplomatic relations, as the former does not recognise the latter’s sovereignty, but the two countries have been engaged in talks led by U.S. President Joe Biden since September to normalise relations that could see Saudi Arabia recognise Israel’s statehood in exchange for American security guarantees.

Saudi Arabia has for decades been one of the United States’ closest allies in the Middle East, with Riyadh gaining access to American military protection, and Washington to Saudi oil—the kingdom’s crude oil reserves are among the largest in the world. However, the relationship has soured under Biden’s presidency over a range of issues, including Saudi oil production cuts, and Saudi human rights abuses being called out by Washington.

The United States, however, is keen on safeguarding its economic interests in the Middle East, and protecting its strongest ally, Israel, while Saudi Arabia’s Crown Prince and de-facto leader Mohammed bin Salman is striving to energetically diversify his oil-dependent country, and open up the nation socially and culturally to more investors and foreign tourists. Its three-way pact with the United States and Israel could come with a defence package and support for a civilian nuclear program by Washington.

The rapprochement is also intended to deter Iran, the region’s other powerful nation. The Persian state—whose people are predominantly Shi’ite Muslims, compared to the Sunni Muslims of Saudi Arabia—has been a longstanding enemy of both the United States and Saudi Arabia, ever since the Islamic Revolution in 1979 helped to overthrow the last Shah, Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, an ally of Washington.

“The revolution, its leaders claimed, was not just against the corrupt Iranian monarchy; it was intended to confront oppression and injustice everywhere, and especially those governments backed by the United States—chief among them, Israel. For Iran’s leaders, Israel and the U.S. represented immorality, injustice and the greatest threat to Muslim society and Iranian security,” writes Aaron Pilkington, a US Air Force analyst of Middle East affairs in the Hong Kong publication, South China Morning Post.

Iran does not recognise the legitimacy of Israel as a state, therefore it is no wonder that the Islamic Republic is one of the strongest backers of Hamas, and uses the organisation—as it does Hezbollah in Lebanon—to undermine Israel’s stability. Iran may have even helped plan the attack on Israel, as a number of sources and experts have pointed out.

In a worrying sign for the U.S., the Saudis and Iranians reached a peace deal this year in April, brokered by China, which is also seeking to expand its influence in the region. Iran and Saudi Arabia have historically competing interests in the battle for dominance of the region, and support different sides in proxy wars, like the civil war in Yemen, which started when the Iran-aligned Houthi movement ousted a Saudi-backed government.

“Iran’s modus operandi in the Middle East has long been to avoid direct involvement but act through proxies—Hezbollah in Lebanon, Islamic Jihad and Hamas in Gaza, and militias in Iraq—to expand its influence and achieve its policy goals,” according to an analysis by the Wilson Center’s Middle East Program. Saudi Arabia cut ties with Iran in 2016 after its embassy in Tehran was stormed during a dispute between the two countries over Riyadh’s execution of a Shi’ite cleric.

However, with the situation in Israel and Gaza escalating, Prince Mohammed bin Salman and Iranian President Ebrahim Raisi talked on the phone for the first time on Wednesday, October 11th, with a senior Iranian official telling Reuters the call aimed to “support Palestine and prevent the spread of war in the region.”

While Iran and Saudi Arabia’s recent rapprochement may have calmed nerves in Gaza, Hamas—the group that has ruled the territory since 2007—was certainly not happy with the upcoming deal between Riyadh and Jerusalem, or the Abraham Accords, a deal brokered three years ago by previous U.S. President Donald Trump, that saw three Arabic nations, Bahrain, Morocco and the United Arab Emirates establish formal ties with Israel.

“All the agreements of normalisation that you (Arab states) signed with (Israel) will not end this conflict,” Ismail Haniyeh, chairman of Hamas’s Political Bureau said, insinuating that the attack on Israel was in fact an attempt to derail peacemaking with Israel, until Palestinian demands have been met. The Palestinians—around 2 million in Gaza, 2.5 million in the semi-autonomous areas of the West Bank, and 2 million in Israel—have moved no closer to their aspiration of securing a state.

Laura Blumenfeld, a Middle East analyst at the Johns Hopkins School for Advanced International Studies in Washington, told Reuters that Hamas may have lashed out due to a sense that it was facing irrelevance as efforts advanced toward broader Israeli-Arab relations.

“Public opinion in Arab countries is still overwhelmingly pro-Palestinian”, even though the “proliferation of conflicts in the Middle East have pushed the issue of Palestine into the background,” Myriam Benraad, a political scientist at the Schiller University in Paris told France24.

The Israel-Hamas conflict may even expand: Lebanese militant group Hezbollah has fired dozens of rockets into Israel in the past week, and Israel has retaliated with strikes in Lebanon. Hezbollah, an Iran-backed Shi’ite group was formed by Iran’s Revolutionary Guard in the wake of Israel’s invasion of Lebanon in 1982.

“Revolutionary Guardsmen instructed Shi’ite resistance fighters in religion, revolutionary ideology and guerilla tactics, and provided weapons, funds, training and encouragement. Iran’s leadership transformed these early trainees from a ragtag band of fighters into Lebanon’s most powerful political and military force today, and Iran’s greatest foreign policy success, Hezbollah,” writes Aaron Pilkington.

Israeli forces withdrew unilaterally from southern Lebanon in 2000 after nearly twenty years of deadly fighting, but Hezbollah and Israel fought a 34-day war in 2006 that left more than 1,200 dead in Lebanon and 160 in Israel.

The European Union classifies Hezbollah’s military wing as a terrorist group, but not its political wing, which is one of the most influential political forces in Lebanon. However, the United States, Israel and Saudi Arabia designate the whole organisation as terrorist.