Danish Minister of Justice Peter Hummelgaard is calling for stricter sentences for violent criminals.

Photo: Lars Svankjær

Non-Western immigrants and their descendants are vastly overrepresented in Danish crime statistics.

Citing numbers from the Ministry of Justice, Berlingske reports that non-Western immigrants, who make up 8.4% of the Danish population, commit 14% of the country’s crimes of aggravated violence and 24.3% of the rapes, judging by number of convicted.

Maybe even more concerning are the figures for second-generation non-Western immigrants. Making up a mere 2.2% of the population, this demographic is responsible for 15.6% of the violent crimes and 8.1% of the rapes.

Put together, this means perpetrators of 29.6% of the country’s violent crimes and 32.4% of rapes are from a non-Western background, despite only making up 10.6% of the population.

“These are deeply disturbing numbers. Therefore, we must take strong and decisive action against this behavior, which is completely unacceptable,” Minister of Justice Peter Hummelgaard told Berlingske.

“It makes me indescribably angry that individuals we have invited into our country repay us by committing rape and severe violence, which destroys other people’s lives here in Denmark,” he said.

Researcher Lars Højsgaard Andersen with the Rockwool Foundation, who specializes in studying crime and minorities, says economic and social conditions are the culprit here: The young men who flee to Denmark have limited resources, are traumatized, and have a hard time entering the job market—which he says needs to be taken into consideration when comparing them with ethnic Danes.

“In societal terms,” Andersen said, “there is a challenge in that we have crime that increasingly has an ethnic face.” Culture, tradition, and the way children are raised also contribute to the discrepancy in criminality between different ethnic groups, he said.

“We actually don’t know what the concrete explanation is. But it is striking that it is almost always people from Muslim countries in the Middle East and North Africa as well as Pakistan and Turkey who fare worse when it comes to crime.”

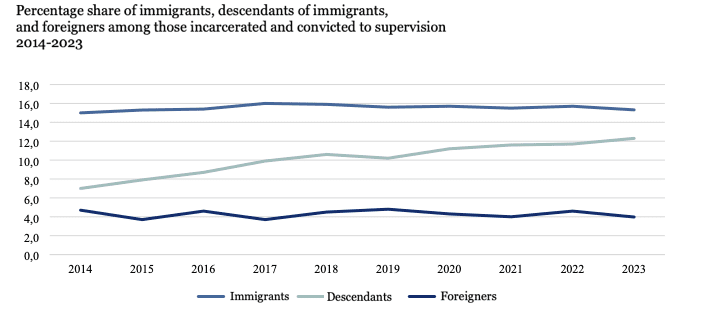

Figures from the Danish Correctional Services show that 27.6% of the incarcerated in Denmark are first- or second-generation immigrants. Adding foreigners (a category that includes illegal immigrants, tourists, and others who don’t officially live in the country) to the count, over 31% of the Danish prison population is—not Danish. That is up from 26.8% ten years ago. Here, again, a troubling trend can be seen: While the number of incarcerated immigrants and foreigners has remained relatively stable, the number of second-generation immigrants in prisons has risen steadily since 2014.

Justice minister Hummelgaard wants tougher—and longer—sentences, particularly for serious violent crimes and rape. But Professor Andersen says the main advantage of longer sentences is that they keep perpetrators off the street. He does not believe there’s a significant deterrence factor in harsher punishments, but instead puts the focus on crime prevention and influencing imprisoned criminals “in a positive direction” so that they don’t go back to a life of crime following a prison sentence.

Crime prevention is also a part of Hummelgaard’s plan for criminal justice reform, as is expanding prisons and punishing less serious crimes in ways other than incarceration to create space in prisons.

To alleviate the space crisis in prisons, in 2021, Denmark contracted with Kosovo for 300 places in a detention center there. So far, no convicts from Denmark have been sent to the Kosovo prison.