One of the largest remaining biological mysteries, how life evolves from the self-organization of a few cells, is one step closer to being unraveled: Teams of scientists from laboratories at the University of Cambridge and the California Institute of Technology have managed to create ‘synthetic’ mouse embryos from stem cells and keep them alive for 8.5 days, thus circumventing the classical insemination of an egg by a sperm that is otherwise the norm among mammals.

The study published in Nature describes the findings of the scientists, who exceeded similar earlier experiments by at least 1.5 days. During these latest experiments, the artificial embryos developed distinct organs, like a beating heart, a gut tube, and even started developing neural folds, the prerequisite to a brain. Jianping Fu, a bioengineer at the University of Michigan, called the findings “very, very exciting,” announcing that “the next milestone in this field very likely will be a synthetic stem-cell based human embryo.”

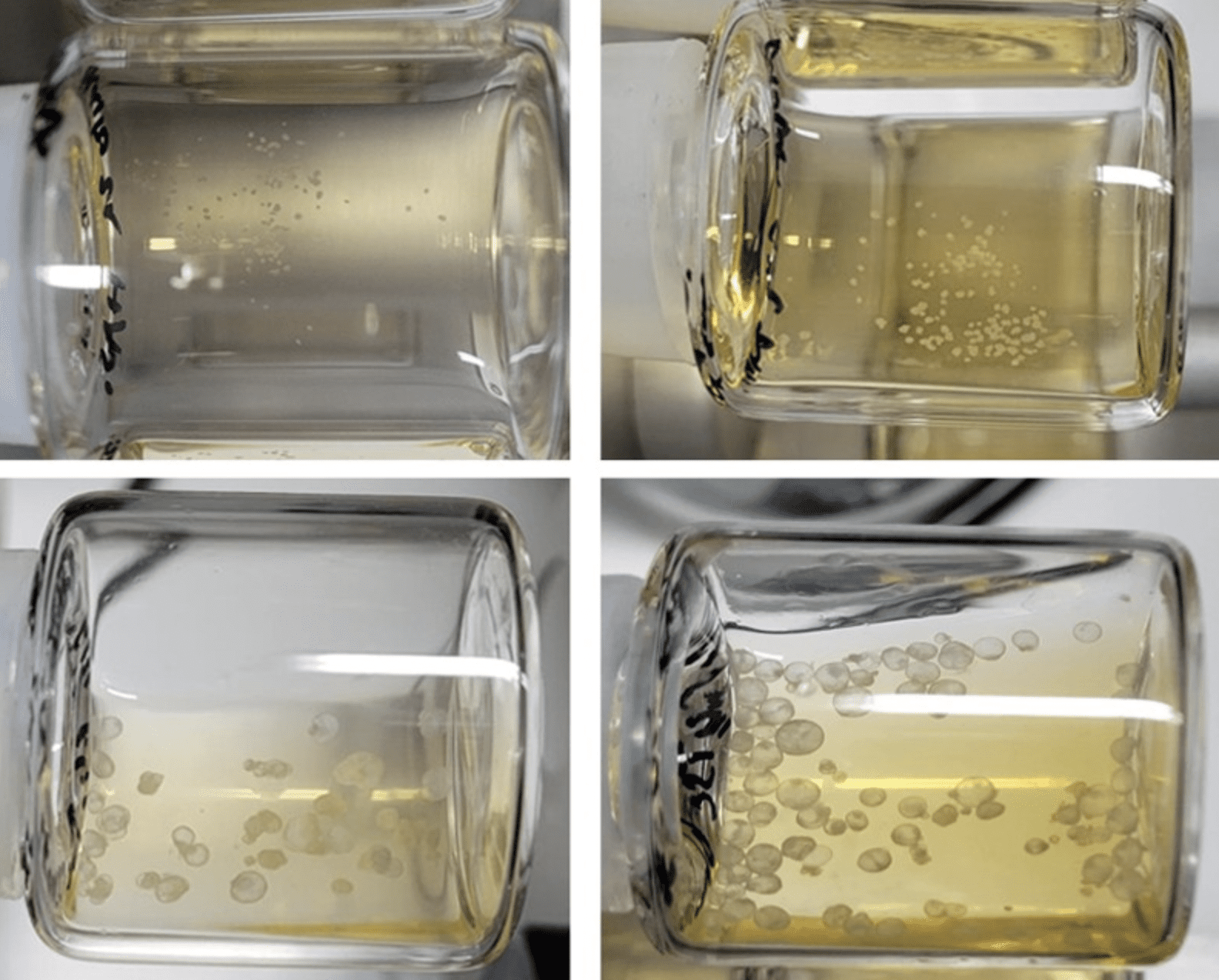

The technology used in the experiment was based on last year’s findings of Jacob Hanna, a stem-cell biologist at the Weizmann Institute of Science in Israel, who developed an incubator that allowed his team to cultivate, longer than ever before, natural mouse embryos outside of an uterus. This technology was picked up by the teams in Cambridge and California and utilized for their own experiments. Hanna said that the synthetic embryos resemble natural embryos, but that they “were not 100% identical,” as one could “see some defects and some changes in the organ size.”

These defects, however, opened the door to other experiments, such as “knocking out” specific genes that affect specific areas of development.

By eliminating the gene Pax6, for instance, mouse heads didn’t develop correctly, mimicking a pattern found in nature as well. The researchers hope that such experiments could shed light on the role of different genes in birth defects or developmental disorders. “We can perturb, we can manipulate, we can knock out every possible mouse or human gene,” an excited Fu told Nature.

Besides hoping to manipulate the genetic code to eliminate certain disorders, the researchers also hope to use such technology in the future to generate new tissues or organs for so-called regenerative medicine. Derived from a patient’s own stem cells, such tissue could be a perfect match for the patient. Magdalena Zernicka-Goetz, who leads the teams in Cambridge and California, said the recent experiments were “a dream come true,” as “this period of human life is so mysterious.” She welcomed being “able to see how it happens in a dish” and hoped to “understand why so many pregnancies fail and how we might be able to prevent that from happening.”

Although some researchers are excited to conduct similar experiments on synthetic human embryos, there are a series of scientific, legal, and ethical hurdles standing in the way of such developments. Organ formation in human cells appears only a month after fertilization, which poses already a significant technical challenge. The International Society for Stem Cell Research did advise against cultivating human embryos past day 14, but removed the limit in 2021, opting instead for guidelines saying that research should have a compelling scientific rationale, as well as using the minimum number of embryos necessary to achieve the objective.

A similar 14-day limitation is in place in the UK for human embryos, but there are no rules for synthetic embryos. Robin Lovell-Badge from the Francis Crick Institute believes that “given the similarity with real embryos, it follows that consideration also needs to be given as to whether and how such integrated stem cell-based embryo models should be regulated.” He warned against thinking of these synthetic embryos “as being the real thing, even if they are getting close,” a sentiment also echoed by Alfonso Martinez Arias from Barcelona University, who said: “This is an advance, but at a very early stage of development, a rare event which, while superficially looking like an embryo, bears defects which should not be overlooked.”

“In the future, similar experiments will be done with human cells and that, at some point, will yield similar results,” said Arias. “This should encourage considerations of the ethics and societal impact of these experiments before they happen.”