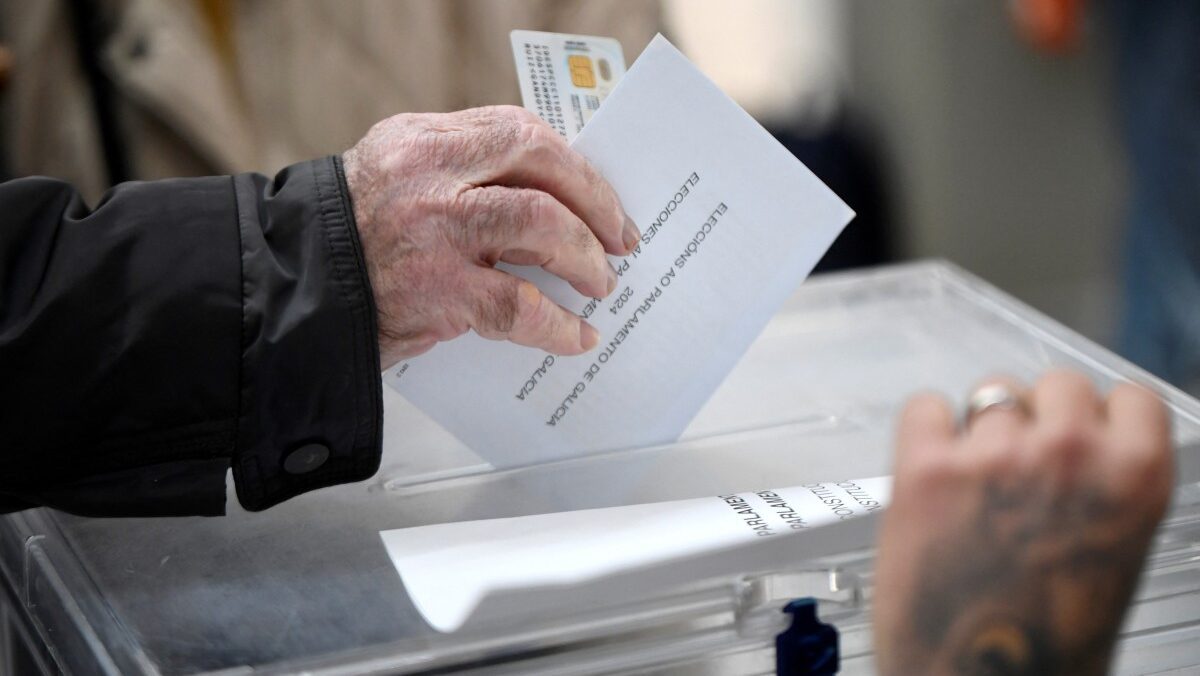

Photo: MIGUEL RIOPA / AFP

Local elections over the weekend in the Spanish region of Galicia have once again proved the weakness of the country’s ruling socialist party as it presses forward with an unconstitutional amnesty law and an almost impossible legislature.

However, the elections also saw the rise of a radical Galician nationalist party.

The center-right Partido Popular, Spain’s main opposition party, solidly won the elections with 40 seats, giving them a comfortable absolute majority in the regional parliament. This marks the fifth election in a row that the PP has won with a clear majority in the region, although the party did still lose two seats in this election. Spain’s governing socialist PSOE party, however, won just nine seats, its worst-ever result in the region.

The country had been eagerly awaiting the election results because polls from the National Statistics Institute had predicted that the PP could lose its majority, opening up the possibility for a coalition government of left-leaning parties.

Despite being one of Spain’s two main parties, the PSOE has now come in third in Galicia two elections in a row, falling below the Marxist-Leninist separatist party Bloque Nacionalista Galego (Galician Nationalist Bloc).

Like the regions of Catalonia and the Basque Country, Galicia has a distinct regional identity and its own language, which is spoken widely and has been taught in schools for decades. So far, however, Galician nationalism has remained relatively modest, particularly compared to the Catalan and Basque nationalist movements.

This election marks a turning point, as the political left once occupied primarily by the PSOE has now clearly been ceded to the ever-more radical Galician nationalists.

“We have broken every barrier, nothing will be the same again,” the party’s president Ana Pontón said, celebrating that her party had gained six seats to number 25 deputies and had its best election results ever.

She had run on a platform calling for the same measures that Basque and Catalan nationalists have either already won or strived for—replacing Spanish with Galician as the principal language of education, the removal of the presence of the national government in Galicia such as by removing country’s two national police forces from the region, and the region’s eventual separation from Spain.

At the same time, for VOX, the region has remained an impossible nut to crack. It remains the only region in the country where the party has not a single seat in the regional parliament.

The breakthrough party in this election was, surprisingly, Democracia Ourensana, a localist party from the city of Oursense whose website states that it belongs neither to the political Right nor Left but is interested only in the good of Oursense. It has in the past, though, formed a coalition government with the PP in the city’s town hall. The party may very well have stolen one of the seats the PP lost.

Overall, if the Galician elections are a reflection of national tendencies, Spain may face even rougher political waters in the years to come, particularly if the socialists’ self-destruction proves to only empower the country’s ever-more-brazen separatist elements.