Migrants gather outside the operational center called “Hotspot” on the Italian island of Lampedusa on September 14, 2023.

Alessandro Serrano/AFP

Migration and asylum-related issues will be at the heart of EU politics over the next five years.

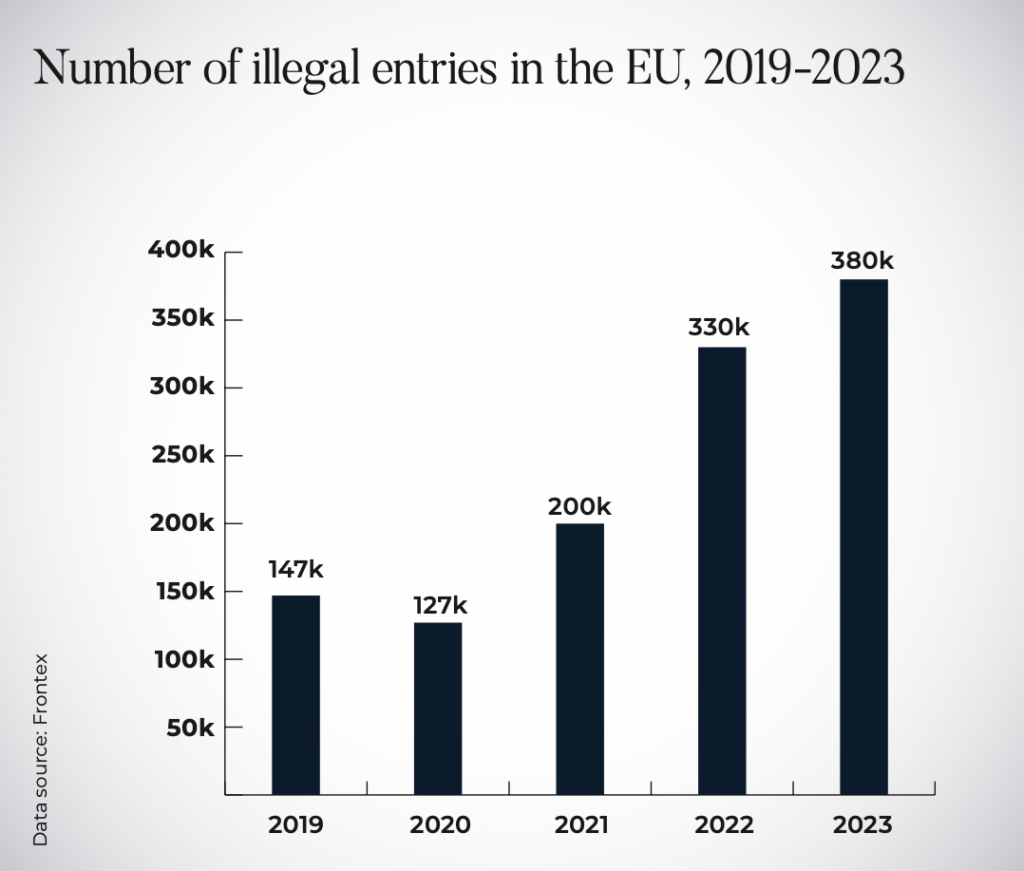

EU elites have failed to grapple with the scale of the civilisational changes wrought by mass migration. As the number of asylum seekers spikes to levels not seen since the 2015 migration crisis, populist, nativist parties are advancing even in traditionally left-wing strongholds such as Sweden and Portugal.

In 2023, a staggering 1.14m migrants claimed asylum in the European Union (plus Norway, Switzerland, Iceland, and Liechtenstein). It marked the fourth consecutive annual increase, a year-over-year surge of 18%, and was only slightly below the record of 1.2m asylum seekers in 2016. Those 2023 numbers don’t include more than 4 million Ukrainians granted refuge in the EU.

Western Europe is facing up to the grim long-term impact of mass migration from the Muslim world. In addition to the threat of jihadist terror attacks and the long-term rise in urban crime, since the October 7th Hamas massacres in Israel, Islamists (aided by the Left) have brought a wave of antisemitism to European streets. Even the EU capital Brussels is plagued by narco-terrorism from warring Arab gangs.

The ongoing migration crisis has left the European elites facing the political upsurge of populism, as the right-wing Alternative für Deutschland continues to break through in Germany and Italy’s Giorgia Meloni leads a reformist nationalist government.

The return of the Taliban in Afghanistan, along with continued destabilisation in West Africa, has further fuelled the migration crisis sparked by the Syrian civil war. Syrian nationals submitted the most applications in 2023 (181,000), followed by nationals of Afghanistan (114,000), Turkey (101,000), Venezuela (68,000) and Colombia (63,000).

The migration of Ukranians after the Russian invasion in 2022 was also an unexpected factor. According to the European Union Agency for Asylum (EUAA), EU countries have provided temporary protection to over 4.4 million Ukrainians since the Russian invasion.

With right-wing parties threatening to shatter the cosy left-liberal alliance of the centrist EPP and the Left within the European Parliament, Eurocrats are belatedly attempting to sound tougher on migration. The best they can propose, however, is to standardise third-world migration through agreed entry points, replacing the current unsupervised rush into Europe.

Central to this is the EU’s Asylum and Migration Pact, for which it currently seeks member state approval within the European Council. Centralising the bloc’s asylum policies on Brussels’ watch, the Pact grants the EU more powers to order member states to accept an allotted quota of asylum seekers every year, and to fine governments which refuse to obey. This system is advertised under the Orwellian-sounding name of ‘compulsory solidarity.’

Populists are right to worry about the EU’s asylum policy being quietly crafted behind the scenes by Swedish home affairs commissioner and open borders ideologue Ylva Johansson, who claims the Pact is just consolidating what are already disastrous EU migration policies.

Fabrice Leggeri, former chief of the EU border agency Frontex and now a candidate for the right-wing Rassemblement National party in France, has warned of the EU’s zealous commitment to mass migration, lamenting that the continent hasn’t seen anything yet in terms of the numbers that will soon be crossing the Mediterranean.

Meanwhile in the Mediterranean, the Italian government is attempting to bring order to chaos on maritime crossings, with clampdowns on NGO boats and agreements with third-party nations such as Algeria and Tunisia, hoping to exchange visas and aid for protecting the EU’s borders. Meloni has been criticised for failing to stem migration from Africa, though the Italian PM has had little or no help from other big EU members or Brussels in attempting to shut ‘Europe’s back door.’

A likely theme of the next five years of EU migration policy will be the relationships with third-party nations proposed to manage border control and return illegal migrants, with Tunisia and Egypt already offered student visas as a sweetener to act as Europe’s borderguard.

At a political level, while a new liberal coalition government could open the flow of migration into Poland, Austria is likely to have a FPÖ-led right-wing administration by year’s end. The Swedish Democrats are slowly improving Stockholm’s lax asylum policies with an eye on leading the next government. Meanwhile Geert Wilders led a right- wing surge on an anti-migration platform in the Netherlands and Vlaams Belang is poised to do well in this year’s Belgian elections.

The calamitous changes caused by Europe’s migration mishaps can no longer be quarantined from public view. Even European Commission president Ursula von der Leyen’s EPP parliamentary group is making tepid efforts to reassure voters that it can handle the migration question as it commits to tripling border force funding in 2024.

When Donald Trump first ran for the American presidency in 2015, European leaders scoffed at the straight-talking Republican wanting to wall the United States off from Mexico. Now, with European capitals bearing the scars of runaway migration, even the EU centre has been forced to backtrack on its earlier optimism regarding open borders.