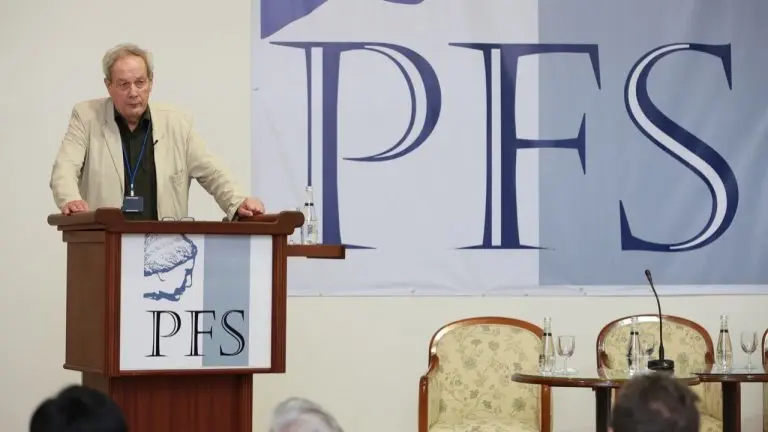

Stone at the 2013 meeting of the Property & Freedom Society. Photograph courtesy of the P&FS.

Professor Norman Stone, the renowned historian who died aged 78 on June 19 this year, was an outstandingly colourful figure on a British intellectual landscape that has long had an accelerating tendency to the flat, dull, monochrome, and ideologically uniform. Norman Stone spoke his mind and lived as he pleased, for which he was both admired and disdained. For some people, nothing is more displeasing than someone who lives on his own terms and yet is rewarded with worldly success. Such people should at least have the decency to suffer poverty.

I was among Norman Stone’s admirers. You could not be in his company for very long without realising that you were in the presence of a deeply erudite man whose fund of historical anecdote was seemingly inexhaustible, always apposite to whatever happened to be under discussion, and brought forth for its own intrinsic interest and relevance, never merely to display how learned he was or to make you feel ignorant. To be at his feet where history was concerned was not so much a humiliation because one knew so little, comparatively speaking, as to be at a delightful and never-ending feast. Moreover, if you happened to know something that he didn’t, he was delighted to learn it.

His brilliance was natural, which is not, of course, to say effortless. No one could write as much as he without effort. At the end of his life he was planning a biography of Count Gyula Andrassy, the great Hungarian statesman, which would have been a labour of considerable difficulty and magnitude for anyone, let alone an elderly man in a poor state of health. It was indicative of his indomitable spirit that he should even have contemplated it.

Professor Stone was very witty and no mincer of words; but he was not malicious towards living individuals, however harsh he could be in his judgment of the dead. Moreover, he knew that, being a controversialist, he was open to criticism and even insult, all the more so as for many years he wrote successfully in the general press, always a source of envy and disdain among academics who believe that penury is a duty, dryness is seriousness, and solemnity a guarantee of profundity. But he took criticism, in good part, almost as a joke. I was once present when he was traduced in public and he did not grow angry, as most of us would have been inclined to do, but rather laughed. As I knew him, at any rate, he was always good-humoured.

He made you laugh out loud even on recondite subjects. Writing of E. H. Carr, the prolix historian of the Russian Revolution in many volumes whose prose would make the Apocalypse seem dull and Armageddon uneventful, he wrote:

As a reviewer [of books], Carr was sometimes just and never fair. He resembled a remote, irascible potentate who would not hesitate to put a whole town to the sword if one of its inhabitants ate his peas with his knife.

Such is the decline in the British sense of humour that proof would probably now be demanded that there had ever been such a potentate, and if so where and when. People would take his ironical obiter dicta as if they were intended as literal truths and then use them to attack him as a bigot with the worst prejudices.

In fact, what he most disliked (though he attacked it with humour rather than bitterness) was piety, to which, perhaps, his Scottish protestant background had sensitised him. Since he regarded life as fun (as well as serious) he particularly disliked the modern form of political puritanism with its heavy leavening of humbug. Indeed, humbug was his public enemy number one; it was not just an unpleasant personal failing but dangerous, in as much as it led to foolishness at best and disaster at worst when it was the basis of policy. Just because religion was dead did not mean for him that piety had died: it merely transferred to something else: politics mainly.

Conservatives such as Professor Stone are usually taken by their opponents to be narrow-minded, enclosed in their little worlds and hating foreigners for being different and therefore worse from themselves. But no man was less narrow-minded than Norman Stone. His experience of life was extremely wide, and even his detractors had to admit that he was a brilliant linguist. He learnt Russian in Haiti and Hungarian in prison in Hungary. He learnt Turkish at the age of 55, when most of us have given up learning anything and struggle against forgetting the little that we have learnt. His Hungarian (he told me) he learned from a Transylvanian gypsy when he spent six months in a Hungarian prison for having tried to smuggle a Hungarian across the border to Austria. He was lucky, he said, because if he had tried to do so a few months earlier he would have been sentenced to nine years rather than six months, and if he had done so a few months later he would merely have been expelled from the country; six months in prison was just right.

His knowledge of literature was immense and he could quote reams of French poetry. He did not disdain statistics, but his history was essentially humanistic, mistrusting grand historiographical generalisations. He never forgot that history is about human beings, about agents rather than forces. His understanding was quick. I mentioned to him one day that I was interested in Haitian history because it contains all the tragicomedy of human existence in peculiarly concentrated form. He replied that we were the only two people who understood that the history of Haiti was the most important of all: a typical example of his feline mental elegance.

The fact that he lived to be 78 rather surprised me, from the purely medical point of view. He was, of course, famous for the amount he drank, and he regarded cigarettes, as well as books, as the precious life blood of a master spirit. My advice to him as a doctor fell on deaf ears, as I knew that they would; my warnings went unheeded, as I also knew that they would. And far from being irritated by this, I rejoiced in it: here was a man who had the courage to live as if the purpose of life was not to live as long as possible, but as well and enjoyably as possible. He was the kind of man who faced danger with his eyes open, and would never blame anyone else for the consequences of his own foolishness (if that is what it was). He knew that you can be free only if you are prepared to accept the consequences of your own actions.

His judgment (in my judgment) was not infallible. I think he was slow to recognise the potential threat or danger that Mr. Erdogan posed to Turkey and elsewhere. This was perhaps surprising because he was no friend of political religion in the modern world. But no man, overall, ever defended common sense in so many human spheres with more wit, panache, and erudition.

This article appears in the Summer/Fall 2019 edition of The European Conservative, Number 16: 53-54.