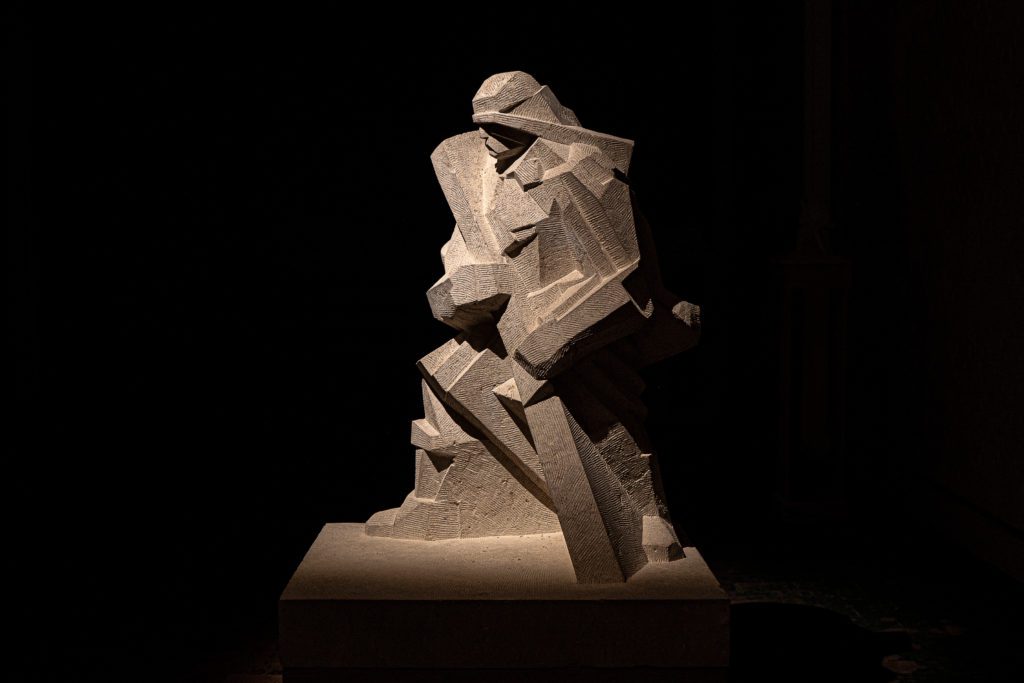

Is there anything so boring as contemporary art? It’s bananas duct taped to walls, vulgar heaps of tyres, and paint literally vomited onto canvas. The academy stands full square behind the postmodern, the vacuous and the tripe, as real art is dragged down by anarchists and censored by dimwits. Last year Italian artist Salvatore Garau sold an invisible sculpture, that is, literally nothing, for $18,300 – it’s enough to drive anybody to despair. Attendant to the cultural elite’s preoccupation with the soulless, real art has become an act of rebellion. I had the pleasure of speaking with one of the rebels, fine art sculptor, Fen de Villiers, about his work, and our cultural malaise. Fen takes momentous blocks of stone and bronze and carves out figures of strength and motion. His dedication to his craft, and his incisive commentary on art and culture have won him many fans. I counted myself among them from the moment I first saw his “Breakthrough” sculpture—and was keen to find out more.

_____________________________

I feel that very viscerally and very deeply, actually. Essentially, my mind is always going, so I have this perpetual hunger of imagination. I have this constant feeling of needing to actually get my hands on something. I need to feel out forms and be busy with my imagination. If I don’t do that, I notice that I lose energy and I become very flat. So, if I’m not engaged in actually making or pushing out some kind of idea in clay, or just sketching something out in clay, or working or drawing something out, then yeah, I suppose my soul feels very flat. I begin to die, in a way.

It’s a very physical process and your body has to be in decent shape. The thing that I often reference about sculpture is the sculptor’s entire body is in combat with the stone. So, it’s this gladiatorial thing. You have the stone in front of you. You’re in a kind of wrestling match. You’re wrestling with the stone to actually find meaning in it. You’re wrestling with it in a very physical way as much as you are in a very, I would say, spiritual way. So, your entire body is caught in the act of sculpting. And that keeps me grounded. I say I’m just a sculptor because it keeps my feet on the ground.

I think that’s a really good way to look at it. I think one has to understand that the sculpture, or the material that the sculptor comes in contact with, is an echo of himself. It’s his body, his energy echoing through the material. It stands there, singing that song of the energy of the sculptor. You see that in sculptures throughout time. The sculptors’ bodies, their energy, their soul is imprinted within that material. Your body, your energy, and your soul is like a fingerprint. It’s totally unique. Even when you watch two artists copy one sculpture, the sculpture is still going to change because their body is imprinted within that work. You can’t get away from that. It’s the rhythm at which you live life that lives in your work. That’s true art. That’s actually what true culture is though, as well.

Yes, you do indeed breathe life into the material. And that material, that life, then echoes throughout your culture and through your people.

I called it “Momentum” because, for me, it’s that deep-seated and primal wish that we can move forward at speed and with glory and with that spirit of adventure, with a wish to go beyond and go farther again and to have the will and energy to do it. You see, when a motorcyclist goes at high speed or a jet travels at a high speed, it takes a while to reach that acceleration point. But once it’s actually reached high speed, it has the momentum and it carries everything with it. The figure on top, the entire mechanical system is carried with it, because it had this energy accelerating it forward.

That momentum, on a spiritual level, is what I feel has to happen with culture today, until we can reach that sense of real fire and life and that will to go on and push forward and dream again. I think it’s the most important thing we can do. I tried to embody those principles in a piece of sculpture called “Momentum,” which is a knight, a figure. It’s a being on a motorcycle, but it’s also an archetype, a god. It’s a reference to speed, the ability to move, and dynamism. It references those things. I felt that it was an important archetype to touch on in our period of stasis.

Because the Vorticist movement was coming together around the time of the first great war, the First World War, it was a very short-lived movement. I think the best way to look at the Vorticists is that they were savagely modernistic in the sense that the language that they were using was entirely unapologetic.

‘Unapologetic’ is a key word in my approach to art, because I think art has become very, very weak and very soft in today’s age. It’s made by pudgy-faced people who are constantly in a state of apology. They’re in a constant state of questioning the fabric of our society, in a very weak—and lacking in glory—manner.

So, what I was attracted by with the Vorticists was—you had one of the main thinkers, Wyndham Lewis, who really brought together this language—the straight line, straight edge. They were inspired, in a very aggressive manner, by the violence of the machine, by this idea that the machine was going to come and revolutionise everything; which it did, of course. But, you know, it went on to create some of the most awful things that happened in the First World War. The First World War was, of course, mechanised death, it was industrial death. Vorticism was a very short-lived movement and it was a very political movement.

The thing that I often say to people is that I look at the Vorticists for a real sense of vital violence and explosive energy on an aesthetic level. I look at that, because I see within it a kind of jagged flame of real Western Faustian will to actually be there, in real space, in yourself, but in culture as well. It’s very unapologetic.

I think in today’s age, everyone’s so afraid. You can take great lessons from the Vorticists, who were unapologetic, direct, and violent. They idolised these things. Of course, today, to even slightly say that you’re for a sort of over-the-top savage confidence, or over-the-top being of yourself—being a British person, being a European, being a Frenchman, you can’t do that anymore.

So of course, it’s very exciting to look at these things. I’m aesthetic and artistic; in some respects, extremist, because I look for the extreme, the very vibrant, and the explosive in culture, because I think if you want to wake people up then you have to look for the explosive energy. And it’s very clear in Vorticism; it’s directly there as it is in Italian Futurism as well, which was a similar movement.

I think that’s a really great way of summing it up. You’re really hitting the nail on the head. Some people disagree with me on this, but my belief is that we’ve hit a period of stagnation. We’re in the information age, but visually, physically, aesthetically, in the real world, we are in stasis. Culture has lost all will to actually, really shout something and be something in a very direct way. I mean, artists used to be seen as heroes, warriors, the warrior poet. You had these painters and sculptors who were there, fighting to actually express and to be there and to say something about who we are in that period.

I’m trying to, as you say, reincarnate to some degree, that flame, that power, that virile energy, because I want to bring it into a period of darkness. I see this time as an aesthetic Dark Age. I like the image of the tank, because it can, at speed, smash through things. I think we need to smash through where we are right now and get into new ground. This was what my show, Breakthrough, was all about. You must break through, we must go on, you must keep pushing forward, you must go on to get out of this stasis.

I often say that I think we need a change in philosophy, a change in culture. I’m a sculptor, so I’m very much involved in the cultural side of things. I think we need a change, we need a glorification, we need life-affirming things right now, because everything’s becoming very bogged down and tiring. So much of what culture is doing now is just about wearing you out, tiring you out, lowering your spirit, reducing your ability to connect to the root of who you are. Most culture that you see today is caught up with petty politics, it’s constantly fighting ‘colonialism’, and there’s the ‘oppressor’ and the ‘oppressed’, and it’s constantly playing this petty political game.

I suppose the thing is, I’m not a politician. I’m not actually someone who wants to even really fight in a political sphere, because for me, the cultural sphere is where everything happens. I don’t care too much for the petty politics of things. If I was to say anything about politics, I think we’re in completely the wrong place.

On another podcast, I mentioned that I take a more primordial and macro view of everything I see. I see where we are politically, and I don’t see any energy there. I don’t see that the politics and the politicians of today are really going to address the important, life-affirming spiritual and cultural elements of our modern life. They’re too caught up in the petty financial worries or caught up in playing off of elements like refugees and all this kind of nonsense. Such issues are, of course important, but until people need to fully understand the corrupt and petty game of politics that politicians are bought and paid for on both sides, and that, essentially, politicians are just simply wearing—like Formula One drivers jackets that have their sponsors’ names written on them—they’re bought and paid for. We’re seeing that more and more with the WEF: the politicians that you think you have, are masquerading before you. So, I consider politics today entirely just a charade. It’s essentially just a game. I know politicians in real life. They’re actors. They’re very good actors, but they’re not there to actually really change anything.

I think that’s a better way to look at it. I believe that culture is paramount and the most important thing. I think that everything happens through a cultural, emotional, and visceral prism in life. It’s always the stories you’re told and you’re brought up with that make the man. It’s always about the nation and the story that runs the nation. But if those stories, and if what you’re being told and what you’re living by, are anti-heroic stories, if the entire system that you operate on is running on a weakness and a constant apology that you even exist, and the culture is so wet and useless, then I’m not even bothered about politics at this point, because the soul of man is dead. The soul of man is not vibrating at the frequency that I believe it should.

There’s no heroism in man today; the politicians are not heroic, they’re not people that I would actually ever want to lead me. I would never want to be led by many of the politicians we have today, because they’re in it for the wrong reasons. The only way that you can cultivate true leaders and true heroes are by people who actually have a cultural route connected to the ground they stand on. The problem today is that most of our politicians don’t care for the ground they stand on. You have someone like Boris Johnson, or Theresa May, or any of these clowns; they don’t care about the English, they don’t care about England, they could be up and gone and go somewhere else, they’re entirely global. They’re not tied to the ground. So, until people understand the fabric and the actual game of what the political system is, you’re constantly caught in a shit show. You’re constantly caught in a pantomime.

Until people are truly brought out of this system and this charade, nothing will change. That’s why I go often back to this idea: I’m not waiting for a leader to come and bring us out of this. I want to cultivate a culture that gives us the strength to have our ground which we will represent in an unapologetic way. Politics doesn’t even come into it for me.

It’s so important to have heroes and leaders, but true ones. The problem I have is that every leader that is masqueraded and paraded around on our media today; they’re not true leaders, they’re managerial class people. They don’t come from a place of honest nobility of the soul. They couldn’t care about anything apart from numbers. They’re not connected to the culture. They have no idea about the poetry of the land. They have no idea about the artists and the music there. They have no idea about the food and the cuisine there. They’re disconnected, they’re global. For me, they have no legitimacy to rule over us. I think the more people understand this, the more they can truly find an honest leader who is beyond this nonsense and really hold them accountable. Leaders must be held accountable; heroes must be held accountable. Being a leader or hero is not a place of ‘I want to be a leader or a hero’. It comes from a place of necessity. The best leaders and heroes are often chosen by other groups of men who can see the ability in them.

It’s knowing that you are part of a culture that spans a few thousand years in the sense that everything that still echoes through our culture today can be traced back to the Greeks, where one can look back at the Romans, look back at certain tribal elements—from the connectedness to what was going on with the Vikings. It entails understanding that, as we developed further through the mediaeval period, there are still elements of our historic culture that remain today. People should know their national story—let’s say on an intellectual level to a degree, and I don’t mean that everyone has to be an intellectual: you just have to understand some of the stories of what connects you to that continuum.

Something that I really enjoyed about modernism, something that really connects me with early modernism from an artistic standpoint, is there was always that thing that Ezra Pound said, which was this idea of “make it new, make it again, renew it.” Everything is based on that which came before, on this idea that there is a constant looking back to go forward. If you don’t know some of the story of who you were, then how do you know who you are in the present, and where you’re going? And I think that’s essentially done by design. I mean, the entire religion of globalism essentially has disconnected everyone from their past, because if you do disconnect people from that, then they’re far easier to push around.

Well, it again goes back to that thing of having heroes. The heroes of the past must be destroyed. You have to disconnect people from this idea of the heroic if you want to weaken a nation or weaken a people. So, this is something that you see time and time and time again. You’ll note that, indeed, right now the hot topic of the day is colonialism: this idea that everyone in Britain was somehow getting a huge benefit out of the colonial empire and this idea that we’re all just slave owners and we’re a terrible group of people and now we must have reparations. Now these are, again, these things that I go back to. You must continue to tell anti-heroic stories if you want to completely debase and destroy the will of a people. This is a very esoteric thing in the sense that, if you want to debase and bring down a people, you must continuously tell them antiheroic stories.

Something that I have noticed is that the archetype of the hero—it’s why I’m actually fascinated by the archetype of the hero—is taboo today, because to actually celebrate heroism as a Brit, as a European, is a very dangerous thing to do in the arts establishment, in the cultural establishment today. They don’t want heroes, because a hero represents something that is unequal. They represent something that has achieved greatness. So, of course, if the hero stands tall—and indeed, the hero stands tall above someone—someone else is getting a hard deal, supposedly in the eyes of this hyper-liberalised world that we live in today.

So, you have to understand, it’s a kind of witchcraft that is going on to constantly propagate this idea of ‘we are the end’. All of our heroes are anti—you know, the anti-heroic story; everyone’s bad. We’re simply just living off these colonial riches that we had, and so we’re the bad guys. But you have to do that if you want to completely demoralise the people. I think that’s what we’re living through. Until people can fully understand this, I don’t believe anything’s truly going to change.

There’s almost an aristocratic element to it as well. Someone like Dirty Harry is a cult figure. People love him because he’s the guy that breaks the rules. He’s the maverick. Everyone wants to be him. Certain males idolise him because he’s the guy that gets the job done—but he breaks the rules, he bends the rules, or he just outright smashes through them because there is a higher purpose to what he is doing. There’s something deeply magnetic about a figure who has that kind of energy. He’s also just ultimately an absolute male archetype. He’s very, very, very masculine. He’s straight talking.

Now, of course, you have to look at this idea of the hero. Everything that Dirty Harry exhibits is exactly what the system today does not want. They do not want you to embody that sort of unapologetic, savage directness, because then you are not a rule follower. You are instead someone who might question or do something that doesn’t fit the prison cell of a cultural system they built around you.

I think the reason there’s a resurgence of this enjoyment of Dirty Harry is because people see within it a way through, because nature will always find a way. What these people embody is actually the primordial elements of culture. They are the stream that runs through and breaks the banks of a broken system and finds a new way. We are as Europeans today and as British people today looking to these figures because we see the system is broken and stagnant. The water has become rotten; it must flow.

The whole reason I came online was to connect with other artists and other culturally driven people—not simply just people involved in politics, but people who see the importance of culture. I have been doing that now, and I’ve now been on the Internet for about a year and a bit. The whole goal for me now is to build an arts collective. I’m looking for other artists. I’m looking for people who see what I’m seeing. And I would say that I’m, thankfully, starting to build those connections with different people. I’ve connected with artists like Matthew the Stoat, Ferro, ōrādemos, and Gio Pennacchietti. I’m starting to find these artists, but I’m still looking for other artists. and at a certain point, I want to bring them together. It’s not exclusively my movement but, along with them, I would like to bring together an artistic collective that will go on and do exhibitions that can give people an alternate answer, that can give people a way out, even if it just allows them to dream of an alternative. That’s what I want to do. I want to find artists and build collectives and have an alternative cultural and artistic system.