One can pour money into a village, but if there are simply no businesses on which to spend it, those who receive that money will quickly use it to buy goods and services at a nearby city. Similarly, politics can promote values, but if we lack the communal context in which to exercise these and in which these might be passed on, nothing will come of it. Like rain on concrete, it may get the ground wet, but nothing will grow.

The Twelvetide is an open gate to benevolent magic, to mages and faeries, a time in which we may recognize what is exalted, as the wise men did, by exchanging gifts and thereby seeing exaltation in each other.

Never has libertarianism, a notoriously loud creed, been so hushed in its concern for liberty.

This is true individuality and true solidarity: We are all free lords subject to no one, yet also dutiful servants subject to everyone. Why? Because of the equal status of all human beings before God. We are all unworthy sinners, yet we are all worthy of salvation through trust in God. Thus, regardless of our earthly status, we all possess equal and inviolable dignity as individuals. And we are all called to solidarity in service to others.

Cancelled for denouncing Arab anti-Semitism, Bensoussan’s publicized trial has crystallized a larger malady that ails France’s intellectual life.

If conservatives seek to uphold the law of the home, it is because they consider it neither feasible nor desirable to transcend it. Hence, they defend the local over the universal and the familiar over the anonymous. Their attachment to their country is founded on reverence and fidelity to that place which made them, and whose geography, law and culture constitutes the fabric of their identity and the object of their true affection.

We should be open to receiving wholeness and beauty, open to the transcendent as it manifests in the bizarre fact of harmony, the startling presence of relationship. In this way we may manifest our oikos in all its coherence, its unity, and avoid developing the kind of resentment that would have us go about compulsively deconstructing our neighbor’s identity.

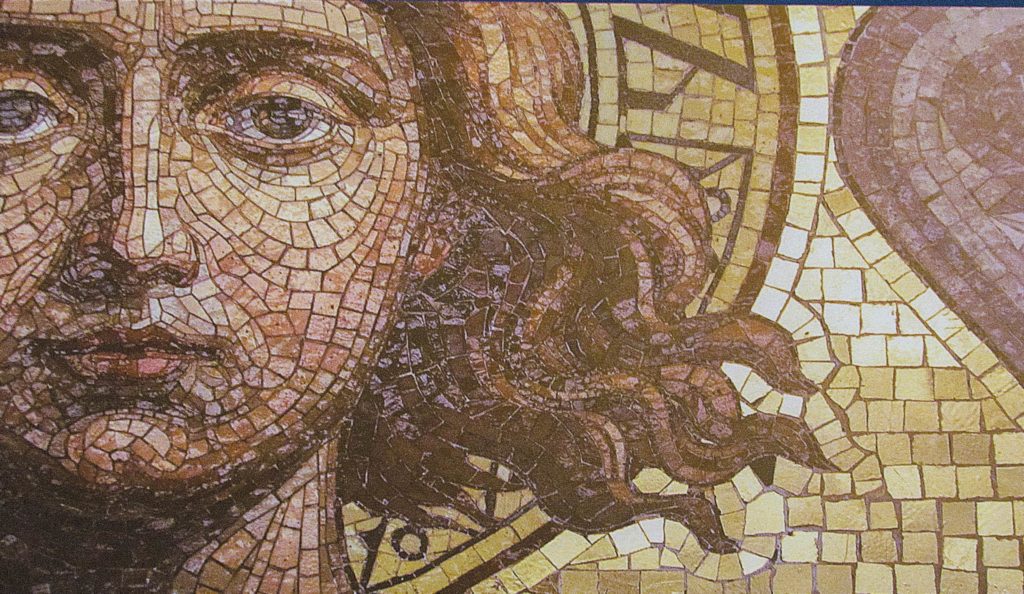

Any state lives by prerequisites which it cannot guarantee itself. No state can survive if it consciously chooses to ignore these prerequisites. For the Serbs, the basis of their political life can only be found in the teachings of St. Sava.

It is easy to see why short-term jobs are conquering the market. They allow people to experience the freedom and moral comfort of a small business, something far more traditional than any nine-to-five job. They are also the natural response to our age of the internet and globalisation, ever-changing circumstances, and the over-bureaucratised corporate cultures.

By insisting on cultural neutrality, by insisting that it merely baby-proofs every hard edge and socket, the new mentality rejects any account of the anatomy of the human mind. It does not care, or does not know how to care, whether aspects of our lives distort our nature.

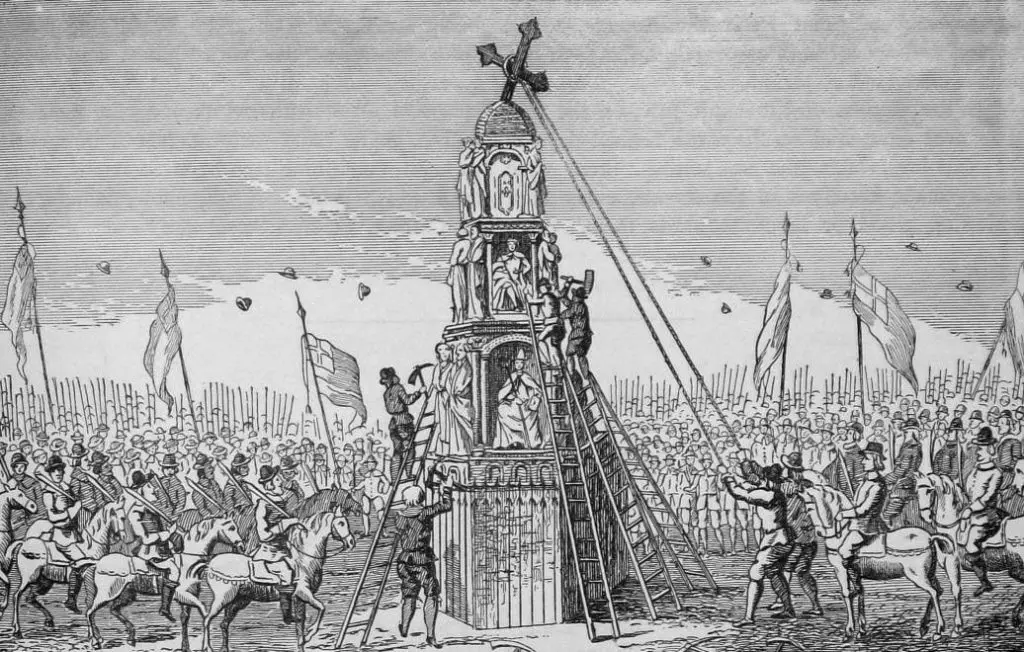

The New Puritans feign an aversion to pride and idols only insofar as it serves their political ends. They should be rejected as menacing imposters. But we should also reject a more sincere application of Puritan principles.

Today, we have almost forgotten the Holy Roman Empire; yet it was the empire that determined the history of Europe for almost a thousand years, and which gave the Germans a common legal framework to develop. This framework—and the shared idea of a Christian Occident—are brought together in the Imperial Crown.

Vienna and New Orleans, despite everything, have remained themselves in the face of larger cultures, consciously or otherwise, attempting (with some success) to reduce them to mere sameness.

Dante Alighieri’s significance stems from his work and extends beyond it. He is the quintessential European figure, epitomising the different strands which make Europe a culturally rich and distinct continent.

The challenge before us is to decide whether we believe in a universe created by a loving God who called us into being and who has destined us for eternal Communion with Himself, or whether we think we can only be ‘free’ by making ourselves like God and imposing our will on our body and the world?

The Enlightenment had its fair share of such confusion. It was a time of truly scientific pursuits; of Voltaire’s brave and sharp remarks; of Hume’s observant rationality. But it also produced Rousseau, whose romantic view of freedom inspired generations of rebels. They thought that only monarchs and nobles could be oppressive, for they had not yet seen tyranny of the people.

In peace or war, the Church Year was a large factor in the home life of the Imperial family, as it was for many of their subjects from Tyrol to Transylvania. Charles and Zita loved Christmas; during Advent Charles taught his children to make small sacrifices. For each of these they could put a straw into the empty manger of the Nativity scene. By the time the Christ Child would be installed on Christmas Eve, there was generally a good supply of straw!

If Brussels wants to keep the project of the EU going, it must abandon its imperial trajectory.

They shed tears of gratitude, knowing themselves unworthy of the boon they were making off with. Joined by the forty-seven pilgrims, the crew now departing totaled sixty-four, eight groups of eight, and like the eight reindeer pulling his sleigh, they set sail with Santa Claus among them.

On a single silent night when all was still and all was bright, Christian Germans and Christian Brits sang together and then climbed out of their trenches to greet each other—and celebrate the birth of Christ.

To be a Christian is to see behind the veil—to see the face of God. Advent–the arrival of Jesus Christ on earth–was, is–the apotheosis of human history—when the Lord tore through the veil of time that separates now and always.

What lies at the root of the totalitarianism that seems to be asserting itself in free societies in today’s West? The answer to this question reveals a fascinating affinity between Ryszard Legutko, a 21st century Polish Catholic philosopher and the 19-century Dutch Calvinist historian and statesman Guillaume Groen van Prinsterer.

Western governments are become more controlling, behaving like overbearing mothers rather than the aloof arbiters they are supposed to be. This is the nanny state at its worst, deciding its naughty citizens did not know what was good for them and, therefore, needed to be kept away from harm.

One December 9th while walking near the foot of Tepeyac hill, Juan Diego was visited by a young woman who revealed that she was the Virgin Mary. After healing his uncle from what had seemed like a fatal illness, the Virgin bid the future saint to climb a hill and collect the flowers that were blooming there despite the Mexican winter. These were strange flowers, for they were European, but had apparently found fertile ground on American soil.

If conservatism is about love for the society that is ours, what are conservatives to do when they look around and find their society increasingly unlovable?

Pre-pandemic, I flew at least one long-haul flight a month and regularly clocked 150,000 air miles annually for the previous twenty years. It was novel for my wife to see me ‘in a flap’ over simple things like checking in online and fretting over the contents of my bags.

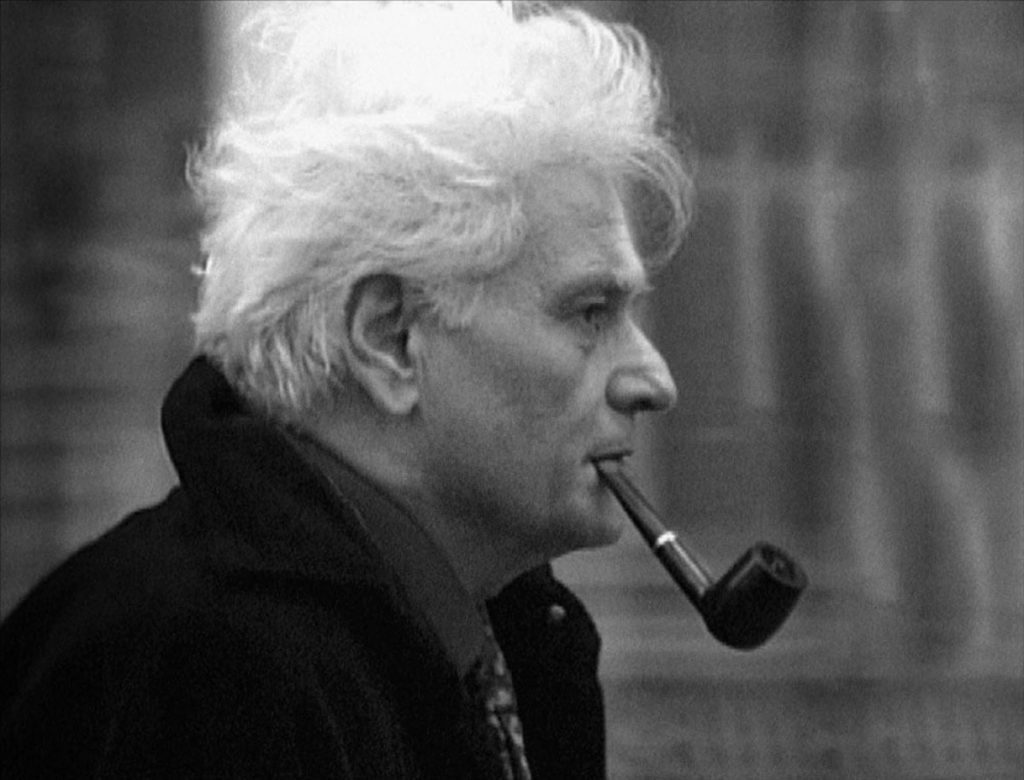

What I saw in Derrida was a man of equal genius whose affirmative understanding of home redeemed French thought from its obsessive oikophobia.

Our ancestors were far wiser than we; they knew that a legal system cannot be an end in itself. It must serve a higher power. If to-day’s courts and judges are to be allowed to retain the prestige and trappings of their illustrious predecessors, let them be once more made to serve what those judges of the past served.

Reigning or not, it is far from beyond the realm of possibility that one or more Royals may one day find the situation forcing or inviting them to mobilise precisely those traditions they embody in order to save their people from whatever dire fate otherwise awaits them.

With the Roger Scruton Memorial Lectures, conservative thinkers and ideas will finally have a space at the University of Oxford.