Nazis. Fascists. Almost eighty years since the fall of the regimes that gave birth to those labels, the terms seem frequently used today. In Spain, anyone not explicitly a leftist on the political spectrum risks being called a facha. In America, an entire cottage industry sprang up attempting to prove that President Trump was a fascist, even as he was mercilessly mocked and criticized by the media with complete impunity. Even after his presidency, the Democratic Party chairman in April 2022 called the Republicans the party of “fear, fraud, and fascism.”

A recent mainstream U.S. outlet dubbed countries that do not embrace the latest transgender ideology “a red flag for fascism.” We have also seen the rise of leftist Antifa (‘anti-fascists’) targeting all sorts of victims, from capitalists to local police to sidewalk bible preachers. These terms have become a lazy, convenient form of political shorthand to use against right of center, conservative, or traditionalist groups or initiatives. The world, especially the West, is full of imaginary fascists, defined as anyone who unapologetically opposes some element of the liberal/Left zeitgeist. The more broadly and promiscuously these epithets are used, the more they seem to lose their power.

Yet one must admit that there are some who shamelessly embrace those labels. Certainly, social media has given, if not actual power, a heightened profile to small, extreme groups of (usually young) hooligans in Europe and North America that enthusiastically embrace Nazi or fascist symbols and rhetoric. The Telegram social media platform is full of neo-Nazi and similar channels, just as it serves as the favorite refuge of jihadists like Al-Qaeda and the Islamic State. This phenomenon is not merely virtual. The opposition alliance that lost to Hungarian Prime Minister Orbán in recent elections was unironically self-described by its leader as including “everyone from communists to fascists.” Nationalists in Latvia, Estonia, and Ukraine have in recent years commemorated local units that fought during the Second World War for Germany against the Soviets.

Both Russia and Ukraine have lively neo-Nazi subcultures (featuring elements like ‘black’ heavy-metal music and neo-Paganism). Ukraine actually has a fanatical military-political organization, Azov (once a “battalion” now considerably larger), that has forged ties with like-minded groups from Europe and America. Some members have joined Azov to fight against Russia in the recent invasion. Rolling Stone recently reported on the misadventures of an American ‘Boogaloo Bois’ member who joined a legion of foreign volunteers fighting for Ukraine. The motivation of these groups and individuals is always a complicated question. How many are dyed-in-the-wool ideologues and how many are just rudderless wanderers, young men looking for an identity (as an example, some Western neo-Nazis wound up joining ISIS) in order to shock the bourgeoisie? Or are adventurers looking for thrills in violence, whether in the streets of European cities or on the battlefields of the Donbas, as a doubtful refuge in a world seemingly grown dull and boring?

The catastrophe of the Second World War and the sheer carnage unleashed by Hitler and his allies should have buried this romanticizing of the Third Reich. But by the 1950s and ’60s a whole range of revisionist memoirs sought to portray a more complicated, often tendentious and dishonest, history of that conflict. Those works, many of them by German former military or Waffen-SS men, sought to rehabilitate the image of armed forces that had, in many cases, fought bravely and effectively for their country, albeit brutally and for the worst of causes imaginable. Some of these memoirs—by Field Marshal von Manstein, General Guderian, Stuka pilot Hans-Ulrich Rudel, who unlike the others, was still an unrepentant Nazi after the war—were bestsellers in English. Others may have sold less well but worked to present an image of a ‘clean’ German army that was somehow completely insulated from the horrors of Nazism.

However, it was not only former Nazis who did this. British author, and World War II veteran officer, Desmond Young’s 1950 biography of Field Marshal Rommel (made into a popular 1951 British film starring James Mason) cemented the image, now considered by scholars as false, of the ‘Desert Fox’ as an apolitical military professional who regarded the Nazis with distaste.

Even more interesting than revisionist histories is war fiction. Two popular authors in particular come to mind: the British historian Charles Whiting (1926-2007) and the Danish author Børge Pedersen (1917-2012), who wrote under the pseudonym Sven Hassel. Whiting was a British Second World War veteran who became a prolific writer–over 200 nonfiction and fiction books published–from the 1950s until his death, including several war paperback series featuring heroes from both the British and German sides. Under the pseudonym Leo Kessler, he wrote one of his most successful series, and likely the most notorious, about a fictional Waffen-SS unit, totaling eight novels about the “SS Wotan Assault Regiment.” Whiting wrote more than 165 novels and 70 non-fiction books. He was a legitimate journeyman writer who seemed to know the difference between fact and pulp fiction.

Sven Hassel was a much more dubious figure. He wrote 15 novels, starting with Legion of the Damned in 1953, in which German soldiers are the protagonists. The characters were represented as anti-heroes more than heroes, but bravely fighting their enemies, especially on the Eastern Front. It is a kind of Nazi Dirty Dozen or Inglorious Basterds. Hassel claimed at some point to have fought in the German Army but actually seems to have been a Nazi collaborator who helped the Gestapo in his native Denmark. A despised figure at home, his books sold quite well in translation. He moved to Spain in 1964, doubtless living well from the proceeds of the more than 50 million copies of his books translated into 25 languages.

An early, mostly unknown (among most English speakers) precursor to revisionist histories and pro-German war fiction first appeared in print in Portugal, of all places, in 1947 as Lutei até ao fim. Memórias dum voluntário espanhol na Guerra 1939-1945 (I fought until the end: Memoirs of a Spanish volunteer in the War of 1939-1945). It was written not by a Portuguese but by a Spaniard: Miguel Ezquerra Sanchez (1913-1984).

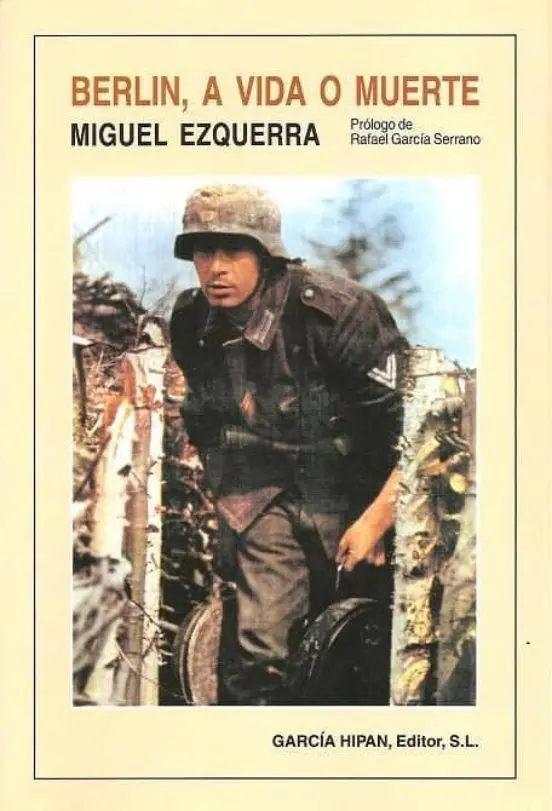

The book was not published in Spain or in Spanish until 1975 as Berlin a vida o muerte (Berlin, to life or death) and has since been reprinted several times. It has also been translated into Italian and French. In 2021, a Spanish version of the original Portuguese edition was published. It purports to be the memoirs of a Spanish soldier who fought during the Second World War on various fronts but particularly in the last days of the battle for Berlin, defending Nazi Germany against the overwhelming might of the Red Army. There are some important differences between the text of the 1947 and the 1975 editions.

Ezquerra was no great writer, but in terms of temperament, he was probably more like Hassel than Whiting: a character out of Baron Munchausen, a teller of tall tales mixing some facts with a lot of fiction. One Spanish expert called him a “mythomaniac,” another dubbed him an ill-tempered farfantón (a boastful liar or exaggerator).

We know some things about Ezquerra. He was an Aragonese, a teacher by profession, who fought on the Nationalist (pro-Franco) side during the Spanish Civil War (1936-1939). He received several medals and was promoted to the rank of alférez provisional (‘temporary officer,’ the joke being in Spain that temporary officers become ‘permanent corpses’). After the civil war, he married and started a family, but like some veterans, he longed for the excitement of war, or at least of life in uniform. His chance came when Germany invaded Soviet Russia in July 1941. An ostensibly neutral but Axis-leaning Spain raised an entire infantry division of volunteers, the celebrated Blue Division, eager to fight the Soviet Union as payback for the USSR’s aid to the Republicans, who lost in the Spanish Civil War.

Ezquerra was able to join in the second tranche of the Blue Division in 1942, serving there until the unit was withdrawn from the Eastern Front near Leningrad back to Spain in late 1943 because of Germany’s deteriorating prospects. But Ezquerra’s book is, despite the title, not about the Blue Division at all but about his service for the Germans in 1944-1945. Returning to Spain, uneasily but truly at peace, he feels compelled to return to the fight against the “savage hordes of the East,” answering the “call of his conscience not to remain at peace while the fate of our ancient civilization was decided.”

Evading a Spanish government now insisting on neutrality, he is able to sneak back into France and contacts the Germans who put him to work. Instead of the Eastern Front, he is employed by the Germans in the West, fighting the French Resistance (which included Spanish Communists), dropping by at the invasion of Normandy, and spending considerable time enjoying Paris with a beautiful White Russian exile. He is able to leave Paris right before the allies arrive (the lead French unit being made up of exiled Spanish Republicans, the 9th company of the Tchad March Battalion, and the 2nd French armored division).

Wild, farfetched incidents are piled one on top of another. He travels from Nancy to Berlin to Vienna, where he meets another fascinating woman in a café, this one a Greek. He then moves to a Luftwaffe unit at Budweis (České Budějovice) made up almost entirely of beautiful women. After two weeks of hard duty there, it is back to Berlin, subsequent participation in the Battle of the Bulge, and then talk of an aborted mission to Brazil by way of U-Boat. Ezquerra seems at times more like a Flashman or James Bond—without the humor, literary skill, or attention to historic detail.

In early 1945, as Germany scrapes the bottom of its personnel barrel, he is asked to put together a military unit composed of Spaniards serving in other units, prisoners, and workers. Such ad hoc units certainly did exist at the fall of Nazi Germany and there is evidence that there was an “Ezquerra Unit” in 1945, but there is not much clarity in what it did.

Unbelievable scenes are followed by plausible ones. He supposedly meets imprisoned socialist, former Spanish Prime Minister Largo Caballero, now chastened, who tells him that “the only consolation I have are some prayers I learned as a child.” Largo Caballero would die at the end of the war just after being liberated from a concentration camp. Ezquerra’s interactions with the Berlin-based Instituto Ibero-Americano, headed by General von Faupel, a former German ambassador to Spain, seem more likely. Incredibly enough, but true, the institute produced, under the leadership of a former Basque priest/Spanish Republic officer turned Nazi publicist, Martín María de Arrizubieta, a propaganda sheet in Spanish combining Nazism, Basque nationalism, and anti-Francoism. Well-known Nazis, Otto Skorzeny, Russian General Vlasov (“a perfect animal” when eating), Himmler, Goebbels, and Eva Braun all make cameo appearances.

Ezquerra refuses the last plane to Madrid, preferring to stay and fight. He is summoned to SS headquarters only to find the unguarded building almost completely empty. High-ranking leaders talk to him about wonder weapons about to appear and save the day at the eleventh hour, while others are overwhelmed with despair and plan suicide (von Faupel and his wife would do so).

He claims that after the Spaniards destroy 20 Soviet tanks (three by Ezquerra himself using a Panzerfaust anti-tank weapon) in vicious urban fighting, he is summoned into “an impressively serene” Hitler’s presence, who then awards him both German citizenship and the Knight’s Cross of the Iron Cross, the Nazi’s highest award. Ezquerra accepts the medal but declines citizenship, telling Hitler that he will remain proudly Spanish. In the 1947 edition, Ezquerra claims a second encounter with Hitler even more incredible than the first.

These notorious passages are totally discounted by the experts. The great Spanish military scholar Carlos Caballero Jurado estimates that 90% of Ezquerra’s book is fabricated. Most German records are missing from those last days and there is, of course, no evidence for the Spanish division’s urban fighting or for Ezquerra’s medal. There is evidence of this type of action and of the awarding of the Knight’s Cross in those last days to foreign volunteers, but they were Frenchmen of the Waffen-SS Charlemagne Division.

Most of Berlin’s last defenders were German; however, there were French, Latvian, Scandinavian, and other nationalities from the broken remnants of Germany’s foreign legions formed earlier in the war. There likely were some Spaniards in uniform too, but nothing is known about their role. Caballero Jurado notes that after the war, in 1965, when Ezquerra tried to get a military pension from the German Embassy in Madrid, all that he could claim was service in the Blue Division, having been trained by German Military Intelligence (Abwehr), and being tasked to create a Spanish unit in Berlin in early 1945. All his wilder claims were missing.

Perhaps Ezquerra heard stories from Charlemagne Division members and substituted himself in their role. There happens to be actual evidence of one Spaniard who fought with the Blue Division beginning in 1941 and also in Berlin in 1945, but his name was Ricardo Botet Moro.

According to experts on the history of Spanish volunteers in Nazi Germany, there are small bits in his story that ring true; Ezquerra may have been in Berlin in 1945. For example, he accurately identifies the obscure commander of a Latvian SS unit known to have been in the city at that time, among other plausible minor details. But the small truths, if they are even that, are overwhelmed by his massive fabrications.

The final pages of the 1975 edition relate a dramatic and implausible trek across Europe, along with killing a Russian guard to escape from captivity (along with two Frenchmen). He then pretends to be an Argentine, making it into the British zone of Germany, and then across Belgium and France pursued by Allied officials and Spanish Republicans looking for him by name. Nearing the Spanish border, he steals a bicycle from a local farmer and is able to pedal his way home. His original edition is less dramatic.

Astonishingly, an elderly Ezquerra gave an interview to journalist Javier Nart for the magazine Interviú in 1982. It was the only interview he ever gave in a life described as “full of mysteries, obscure points, surprises, and surely, fantasies.” Ezquerra added new details of his supposed German military career that went beyond the book and embroidered an even more colorful postwar career, including service in the French Foreign Legion in Vietnam and the anti-Castro legión anticomunista del Caribe (ALC) set up by Dominican dictator Trujillo, all without a shred of evidence.

As a work of serial military fabulism, Ezquerra’s book is an interesting cultural artifact. I laughed more than once at the author’s sheer gall, but Ezquerra himself is an unpleasant figure disarmed by his own text, an uneasy mixture of boasting, fact, and fable. A literary liar is bad enough; a Nazi literary liar seems even more obscene. Miguel Ezquerra’s greatest significance may lie in the fact that he was one of the very first of a lamentably long-lasting phenomenon: the Nazi poseur, which continues to this day, seemingly both buffoonish and belligerent.