Ever since the year of our Lord 1432, the main church of the Flemish city of Ghent has held a unique piece of world class art comparable to the ancient wonders of the world. That year the Flemish painter Jan Van Eyck (ca. 1390-1441) completed the polyptych “De aanbidding van het Lam Gods” (Adoration of the Mystic Lamb) or, as it is known in English, the Ghent Altarpiece.

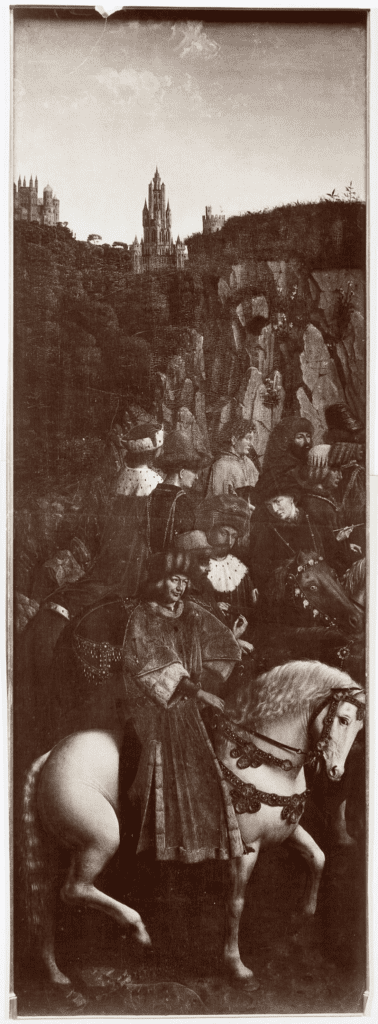

This monumental whole consists of 20 separate wooden beautifully painted panels. The central idea of this work of art is the redemption of mankind through the sacrifice of Christ. The brilliant painter executed this polyptych on behalf of a rich but childless Ghent couple: Joos Vijdt and Isabella Borluut. Both donors are depicted at the bottom of the exterior panels of the altarpiece.

This is without doubt a masterpiece of European art history. The Ghent Altarpiece is on the same lonely height as the Parthenon on the Acropolis in Athens, the Sistine Chapel in Rome, and the cathedral of Chartres.

The wandering altarpiece

The Ghent Altarpiece has had an eventful history. It can safely be said that the altarpiece rides on the waves of history itself: staying in one place when history is calm, and moving when history is turbulent. During the 16th century iconoclasm, the altarpiece was threatened with destruction by zealous Protestants. At the end of the 18th century, the French occupier stole the Ghent Altarpiece and transferred it to Paris. After the French defeat at Waterloo in 1815, the altarpiece returned to the Netherlands. It was not until May 10, 1816 that the entire Ghent Altarpiece was back in the Ghent main church. Barely a few months later, this masterpiece was again mutilated.

On December 19, 1816, a clergyman of the cathedral thought it would be a good idea to sell all the exterior panels (except the nude figures of Adam and Eve) to an antiques dealer for a ridiculously low sum.

Ultimately, the exterior shutters were purchased in 1821 by Frederick William III, King of Prussia. He donated the altarpiece to the Königliche Gemäldegalerie in Berlin. There, in 1894, the side panels—on which both the front and the back are painted—were sawn in half so that both sides could be displayed to the public at the same time.

“Der Genter Altar” was a showpiece in Berlin’s Gemäldegalerie for many years. After the First World War, however, the Treaty of Versailles (June 28, 1919) obliged the defeated Germany to hand the wooden panels—which were perfectly legal German possessions—over to Belgium free of charge. This naturally caused a great deal of dissatisfaction in Germany.

The theft of the “Just Judges”

On August 21, 1921, the Belgian state also gave the side panels with Adam and Eve (which were never sold) to the Ghent cathedral. For the first time since 1816, the Ghent Altarpiece was again complete! However, 14 years later, on the morning of April 11, 1934, two wooden panels were discovered to have disappeared: the painting with Saint John the Baptist and the multicolored panel with the “Just Judges.” It took almost twenty days after the theft for an anonymous person to send extortion letters to Mgr. Coppieters, Bishop of Ghent.

On May 29, 1934, the unknown thief returned the John the Baptist panel free of charge via the left-luggage office at the Brussel-Noord train station. He thus proved that he was indeed in the possession of the “Just Judges. For that panel, however, he demanded a ransom of one million Belgian francs. Negotiations went on for months, with the blackmailer sending letters to the diocese and the bishop replying via messages in the Belgian-French newspaper La Dernière Heure. But the Belgian government forbade the Church to pay the ransom. On October 1, 1934, the anonymous blackmailer sent his 13th and final letter.

About two months later, on November 25, 1934, a certain Arsène Goedertier died in Wetteren near Ghent after giving a speech at a meeting of the Catholic Party. The man was not only a sexton and stockbroker but also had political ambition, wanting to become a senator for the Belgian Christian Democrats. Just before his death Goedertier reported to his lawyer, George De Vos, that he knew where the “Just Judges” was located. Goedertier referred to “a file about the whole case” that is in his office at home.

Attorney at law De Vos, who, like Goedertier, was a supporter of the Catholic Party, investigated the office of the deceased stockbroker with Julienne Minne, Goedertier’s widow. To his great astonishment, lawyer De Vos found—among other things—duplicates of the extortion letters to the bishop. This seems to indicate that Goedertier was indeed the blackmailer. However, nothing proves that Goedertier himself stole the panels, and De Vos surmised that others actually perpetrated the crime.

De Vos immediately realized how compromising this file was. Not only the Church, but also prominent figures from the Catholic Party are involved in the case. De Vos, who himself was striving for a parliamentary mandate, therefore had every interest in preventing this enormous scandal from being reported.

A disastrous judicial investigation followed, lasting until 1937, a long three years. Crucial witnesses, most notably De Vos were never questioned by the Belgian court, and no progress on the theft was made. The cover-up, then, remained covered. In 1937, the file was closed because Goedertier, who was then believed to be the perpetrator, had died. His lawyer De Vos, meanwhile, had been given a seat in the senate.

A replica of “The Just Judges” panel of the Ghent Altarpiece , painted in 1939 by Jef Van der Veken.

The altarpiece in the war

The outside world, however, ultimately intervened. On May 10, 1940, the German Wehrmacht invaded Belgium, and the country became occupied. As early as June 1940, Oberleutnant Henry Koehn began a professional investigation ordered by the highest levels of the Nazi-regime via an organization that was called the Kunstschutz.

He interrogated—for the first time!—crucial witnesses. The German researcher formulated his conclusions in early 1942 to his boss Count Wolff-Metternich: Goedertier was not the thief! On the contrary, he discovered the thieves himself … among the Ghent clergy!

Count Wolff-Metternich was sidetracked on the matter in 1942 because he stood in the way of Nazi-bigwig Herman Goering. Count Wolff-Metternich didn’t like the idea that Herman Goering was robbing Europe of its paintings so that the Nazi-leadership could decorate their houses down to the smallest rooms with world-class paintings and drawings.

Henry Koehn, being a subordinate of Count Wolff-Metternich, was also ordered to stop his research. From that moment on, the egregious Schutzstaffel (SS) was ordered by Herman Goering to take over the Kunstschutz. The conclusions of the Kunstschutz under SS leadership were locked away in various archives (where they remain to this very day), so nothing can be said about the German investigation after Henry Koehn.

The German officer Koehn wrote all this down in an extensive and solid file from the end of his involvement until his death in 1963. Several times he declared to his stepdaughter Helga Koehn that the Church owns the panel. Helga Koehn carefully stored her stepfather’s files.

Karel Mortier

In 1964, the Ghent police commissioner Karel Mortier received a copy of this file. Mortier has published no fewer than four books (in 1966, 1968, 1993, and 2005) on the theft. While he mentions Koehn’s findings in his work, he does nothing with them. In fact, Mortier laughs at the notion that the Church is involved in this case. According to the former police commissioner, Goedertier officially remains the perpetrator.

From 1966 to 2001, Karel Mortier practically had a monopoly on research into the Ghent art theft.

From 2001 onwards, however, things began to move again because an amateur detective, Gaston De Roeck, appeared on the scene. He published his findings on the internet as “I Goedertier,” and countless people have consulted his site. De Roeck mentions the names of the guilty: Arthur De Meester, canon of St. Bavo’s Cathedral and secretary of the diocese of Ghent; Camille Van Ongeval, former canon of St. Bavo, director of St. Anthony’s home for the elderly; and Gustave Van Ongeval, pastor-dean of the Sint-Gertrudiskerk in Wetteren. Arsène Goedertier later became a sexton in that church.

In the summer of 2002, when this hype on the internet reached its peak, something remarkable happened: Professor Robert Senelle (1918-2013), constitutional specialist and confidant of the Belgian Royal Court and other prominent figures, made a statement to Paul De Ridder. De Ridder, a doctor in medieval history and head of department at the Royal Library of Belgium, has been committed for many years to the cultural-historical patrimony—in particular the cathedral of Brussels, its archive, and its collection of early music scores. Senelle declared to De Ridder that Goedertier was not the perpetrator, and he confirmed Henry Koehn’s statements from 1942.

Latest developments

Robert Senelle also told De Ridder that he had been conducting discreet conversations for some time to reunite the “Just Judges” with the other panels of the Ghent Altarpiece without scandal. Senelle and De Ridder worked together on this for many years. By 2009, De Ridder had already informed the bishop of Ghent that Arsène Goedertier was not guilty of the theft. Sadly, Senelle died on February 13, 2013, but De Ridder made an official statement to the public prosecutor of Ghent in the autumn of 2013. As a result, the court asked De Ridder, the historian and archivist of the Brussels cathedral, to announce to the official Belgian television channel that negotiations had been going on for years about the return of the panel. On March 28, 2014, the Bishop of Ghent, together with De Ridder, called for this matter to be settled amicably.

Under the auspices of the Flemish Club for Arts, Sciences, and Literature Paul De Ridder has published two fascinating books about this enigmatic art theft. The reader is, as it were, present at a number of crucial conversations about this intriguing case.

This case is still alive. The Ghent Altarpiece continues to ride on the waves of history. So, what is its next destination? Will there be a resolution soon?

This is the first essay in a series on the Ghent Altarpiece theft and was written with the cooperation of Dr. Paul De Ridder.