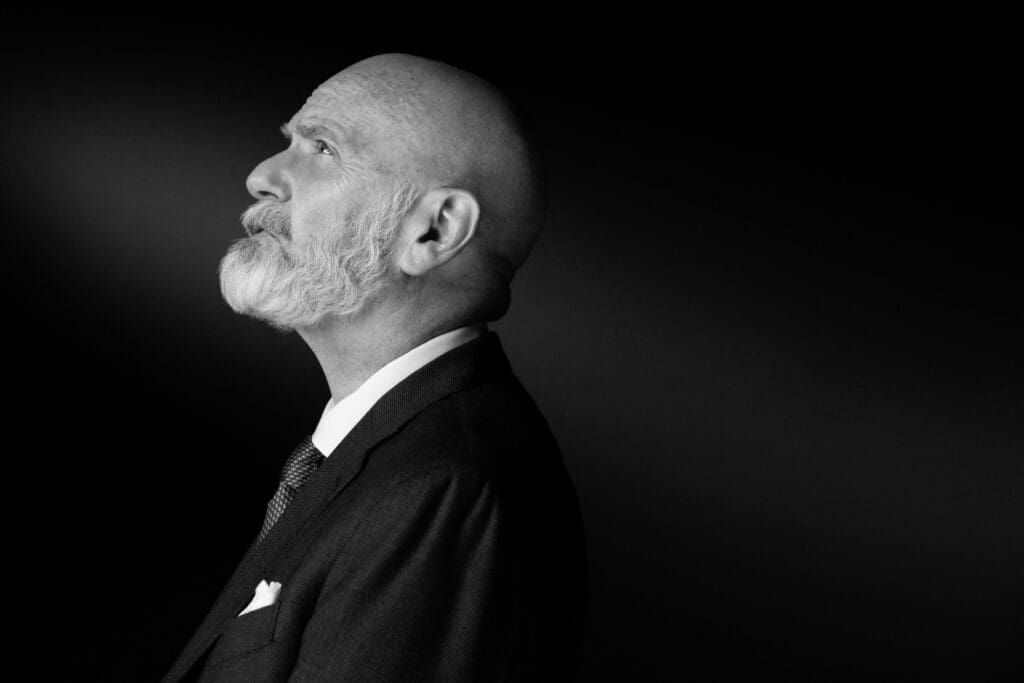

Iván Vélez is a Spanish architect and historian, as well as a member of the political party VOX. Writing from the perspective of philosopher Gustavo Bueno’s ‘historical materialism,’ he has numerous books to his name. The following interview focuses on his El mito de Cortés (The Myth of Cortés), where he delves into the career and impact of the paradigmatic conquistador.

To begin, we should at least gesture towards the still-operant Black Legend. In this regard, to what extent would you consider that the work of Cortés was civilizing and, therefore, coherent with what Bueno describes as the Hispanic monarchy’s ‘generative’ (as distinct from ‘predatory’) project?

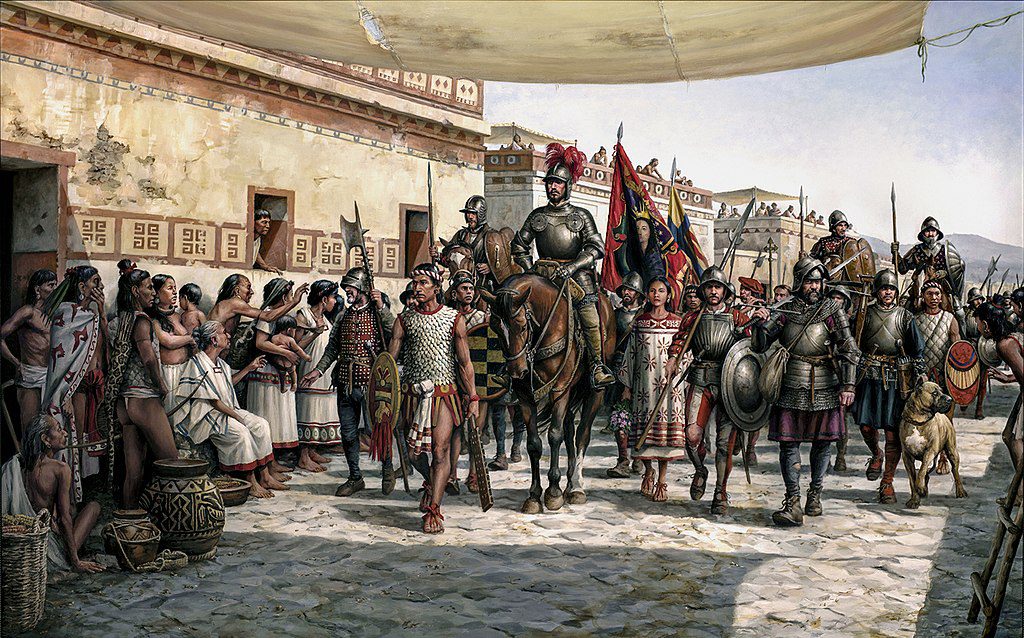

The work of Hernán Cortés paved the way for the establishment of Spanish institutions in Anáhuac.

In fact, all the juridical framework elaborated in Veracruz (with the purpose of breaking with Velázquez de Cuéllar, governor of Cuba), in careful conformity to Spanish law, has as its background the denunciation of the personalistic deviations which the governor of Cuba had engaged in.

Cortés even founded a hospital that is still operant, as well as promoting industries such as silk.

In short, the conquistador facilitated the implantation of Hispanic institutions—political, legal, religious, economic—to which the natives of the land were no strangers, in the ancient Mexica empire.

What would a so-called “luminous legend” around Cortés consist of?

The term “luminous legend” (as opposed to “black legend”) refers to constituting a canon of features describing this successful conquistador capable of conquering the Mexica Empire: In his time, Cortés became the model for those he defined as his own emulators. Cortés combined military and diplomatic talents, and his actions served to implant the Christian religion in lands dominated by idolatry, meeting both the territorial and spiritual objectives of the Spanish Empire.

To what extent does Cortés rely on Castilian law (I am thinking of the founding of Veracruz and its disconnection from the authority of Diego Velázquez)?

He does so when founding the city of Veracruz. Cortés knew Castilian law thanks to his youthful attendance at the Salamanca university while staying at the home of his uncle, the notary Francisco Núñez de Valera. With that training and the knowledge he had of the people who lived in Cuba, he was able to draw up a series of documents that totally discredited Velázquez, while showing his loyalty, and that of his companions, to the king.

What idea of political authority did Cortés have (his own, as well as that of Emperor Carlos)?

The classical one in the Christian world, in which political power, which comes from God, is given by the people to the king, to the sovereign. In all his documentation, one can observe an unwavering obedience to Emperor Charles.

Did Cortés want to facilitate a Christianized and politically subordinated Tenochitlán, but otherwise intact?

Cortés always acted with great vehemence against idolatry and tried to extirpate such horrendous practices as anthropophagy and human sacrifice, institutions incompatible with his Christian vision of the world. Cortes, as he himself wrote, would have liked to hand over so magnificent a city as Tenochtitlan to the king of Spain, but the city was razed to the ground during his siege.

What was Cortés’ view of encomiendas/commandeering rights, and how did this view evolve over the course of his life?

Cortés used the term “depósito de indios.” In his mature stage, he advocated for the maintenance of the “encomienda” in order to anchor the Spaniards to the land and guarantee the security of the clerics so that their missionary work would not be lost.

How would you address the image of the cruel Cortés—for example, in relation to the accusations hurled at him by Bartolomé de las Casas?

We may describe Cortés as severe, rather than cruel. His name was saddled with the image of a cruel man by Las Casas. However, at several points in the conquistador’s Letters of Relation, we find don Hernando moved by the suffering of the Indians.

He did, however, rigorously apply justice, both to Spaniards and Indians. Very simply: had he not done so, his enterprise would have come to naught.

Have historians neglected the primary sources concerning Cortés and the conquest of Mesoamerica, preferring to reiterate clichés?

There has been much progress in recent years concerning the study of indigenous sources, which often provide new nuances.

The interpretation of events that one finds in these sources, is, at times, coming from a very particular perspective, with its own ideological bias.

In relation to the primary sources, several lines have been maintained over time. Some emphasize Cortés, while others, especially that of Bernal Díaz del Castillo, pay more attention to the collective (the men he led).

It must be kept in mind that we are not dealing with neutral narratives, but with texts that seek merit (fame, renown). In any case, archival research on both sides of the Atlantic will allow us to delve into details that offer a more realistic picture of what happened during that time.

What falsehoods about Cortés would you highlight as particularly flagrant?

The most popular is the non-existent burning of the ships (to avoid retreat) and the much less known accusation that he murdered his first wife.

In any case, more than any one specific falsehood, I would highlight the general, darkly legendary aura that surrounds a character of his stature.

What do you think of the idea that Cortés was identified with the god Quetzalcoatl by the Aztecs? And how would you characterize the agenda of the Florentine Codex writers?

From very early on, as Cortés himself took pains to clarify, he was perceived for what he was: a man.

The legend of Quetzalcoatl is, nevertheless, useful in presenting a Moctezuma subject to religious fanaticism who would have facilitated the conquest of his empire.

However, the Huey Tlatoani already knew about other bearded men and was forewarned against them. Fray Bernardino de Sahagún’s informants contributed to this image.

Does the later rebellion of the conquistador’s sons (Martín the Spaniard, Martín “el Mestizo,” and Luis) display any continuity with their father’s project?

The rebellion was motivated by Spain’s so-called New Laws, which limited the degree to which an ‘encomienda’ could be inherited.

The world of landed nobles that had grown up around the figure of Cortés was collapsing, so who better to lead a revolt on behalf of that order, albeit symbolically, than his son?

You bring up a certain resemblance between Cortés and Alexander the Great, what parallels do you find most striking?

Both oversaw processes of vast imperial expansion. Cortés’ stature could only be compared, even in his time, with that of Julius Caesar, Hannibal, or Alexander himself. His maneuver at the battle of Otumba is also reminiscent of Alexander in Gaugamela.

Beyond Cortés: to what extent were pre-Columbian structures preserved in Mesoamerica after the conquest?

Many of these structures were preserved. We must take into account the small number of Spaniards who went to the New World in the decades following the conquest.

The Crown itself understood this, to the point of granting titles of nobility to those indigenous rulers who already enjoyed power over the local population.

This entailed the conservation of existing institutions, duly purged of those customs incompatible with Catholicism or Spanish law, wherever such could be enforced.