The COVID pandemic was the most disruptive peacetime event in the world so far in this century. Many governments reacted with downright hysteria, forcing their citizens into lockdowns and vaccinations, closing schools and businesses, in some cases canceling life as we know it.

We have many lessons to learn from this pandemic, the first being that pandemics have happened in the past and will happen in the future. We cannot panic every time a new virus emerges, nor can we forget how thin that line is between freedom and tyranny. Far too many among us genuinely believed that government could treat individual freedom as a light switch and that they could turn it off without any serious repercussions.

Some proponents of totalitarianism ‘for the good of society’ have grown uncomfortable with the realization that they might have been on the wrong side of history. Now they beg to be forgiven for their transgressions.

It is always welcome when people learn from their mistakes. Hopefully, freedom will prevail, and perhaps even stand stronger next time. Another thing to hope for is that people will not blindly ‘trust science’ in the future; tyranny is tyranny, even in sheep’s clothing.

However, there is also a less dramatic lesson to be learned from the pandemic, one that does not grab headlines but still greatly influences people’s lives. While all eyes have, understandably, been on the terrible consequences of the lockdowns and the vaccine side effects, the pandemic has put Europe’s health care systems to the test in ways they have not been tested in a very long time.

The results are dramatic, with clear and significant policy implications. Health care systems with a high degree of government funding were ill-prepared for the pandemic; systems with a higher degree of private and semi-private funding had a much better capacity to respond.

Nowhere is this more obvious than in the supply of hospital beds, which of course is a key metric in pandemic preparedness. A health care system with plenty of bed capacity under normal circumstances can quickly scale up its operations in order to secure a proper volume of inpatient services for pandemic victims.

By contrast, a health system that has few beds to spare under normal circumstances easily ends up resorting to drastic non-medical policy measures, such as school closings and citizen lockdowns.

But does this not mean that we can save ourselves in the next pandemic if we just scale up our current health care funding?

Conventional wisdom would suggest as much, and it is a good theory—in theory. In practice, not so much. But before we get there, let us have a look at the different forms of health care funding.

Generally speaking, health care is funded from four different sources:

There are at least as many different ways to combine these four funding sources as there are member states in the European Union. However, all EU member states did two things to contain the fallout from the pandemic. First of all, they increased total health spending from 2019 to 2020—the only exception is Belgium, where total spending went down by 1%.

In four countries, the increase was more than 10%: Bulgaria (+19.7%), Czechia (+19.5%), Hungary (+16.9%), and Ireland (+11.3%).

Second, the increase in health spending consisted of government funds and mandatory social insurance programs. There were noticeable declines in funding through voluntary programs and out-of-pocket payments.

In short, practically every health care system in Europe became more dependent on government during the pandemic. This is expectable: government can appropriate more money for its own programs simply by borrowing from its own central bank. Other funding models, including social insurance programs, depend on revenue sources that declined during the pandemic. When government shut down private-sector economic activity, non-government health care funding models experienced a decline in revenue.

Some social insurance programs can rely on government funding; the exact model varies from country to country. When their revenues depend on business payrolls, and businesses are forced to shut down, there is no escaping that their finances get tighter. However, broadly speaking, it appears to be the case that government helped social insurance programs stay afloat: in the 23 EU member states where these programs are part of the health funding model, 18 experienced an increase in their funding, with a decline in the remaining five.

Cyprus stands out here: the spending by social insurance organizations more than tripled from 2019 to 2020. In fact, social insurance assumed a major role in funding Cypriot health care during the pandemic, while direct government spending declined by 8%.

At first glance, it would seem natural to rely on government as a general source of health care funding. After all, with its ability to simply have money printed in order to meet all sorts of challenges, government can handle any adversarial situation. Right?

This is not the place to discuss the connection between monetized budget deficits and inflation. There is another apparent reason why government should refrain from playing any major role in funding health care. To see why, let us look at an interesting pattern in the increase in government health spending in 2020.

There are 26 EU member states included in Eurostat’s health care database (the numbers from Malta are limited and essentially useless). To put more meat on our analytical bones, we add Iceland, Liechtenstein, and Switzerland to our analysis.

In 2019, in 15 of these countries, government was responsible for at least 20% of health care funding.

On average, in the 2020 pandemic year, government increased health spending by 11.4%. By contrast, in the 14 countries where government paid for less than 20% of all health care, it increased its pandemic-year spending by an average of 58%.

In other words, the smaller the role government played going into the pandemic, the more it increased its spending during the pandemic.

Slovenia stands out as the extreme. In 2019, government paid for 5.8% of all health care; in 2020, it increased its funding of medical services by 133%. Slovakia is a close second: its government funded 3% of health care in 2019, which amounted to €151.5 million. In 2020, that number grew by 90% to €302 million.

There is a simple but important fiscal reason why governments with small responsibilities for the health care system can so readily scale up their funding. The more of a nation’s health care that is paid for directly by government, the larger that spending becomes as a share of the total government budget. Any increase in health care funding will significantly affect the government’s budget balance.

Things get really complicated when government simultaneously has a big responsibility for funding health care and usurps the powers to force its taxpayers to shut down their tax-paying operations. Suddenly, extra pandemic funding becomes an urgent fiscal problem, where a legislature has to choose between

a) violating statutory or even constitutional requirements to balance its budget, and

b) starving its pandemic-plagued health care system of funding when that funding is needed the most.

This rather cynical choice explains why governments with big health funding requirements could not provide much of a boost during the pandemic. Scandinavia is a case in point: in Denmark and Sweden, government directly funds practically all health care; the two countries saw some of the smallest increases in total health care spending during the pandemic.

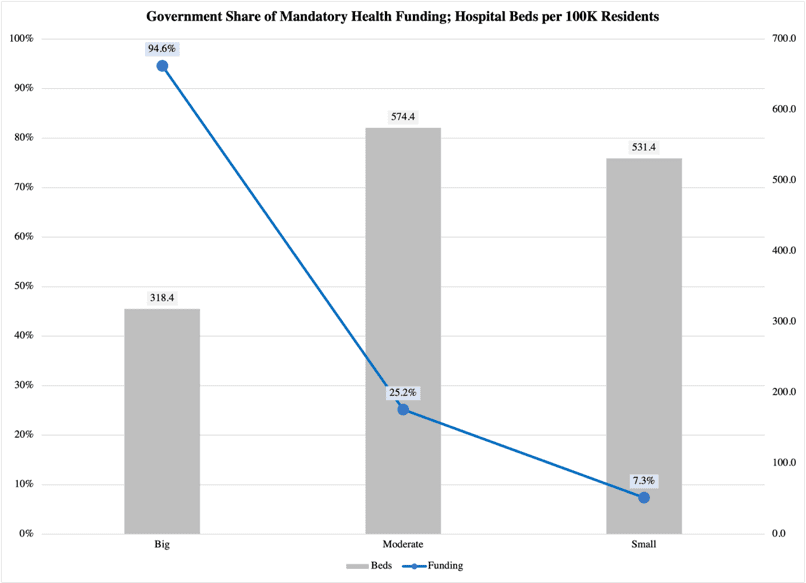

As mentioned earlier, a big role for government also has consequences for the capacity of a health care system to deal with a pandemic. Figure 1 below reports the number of hospital beds per 100,000 residents (the line) and the share of mandatory health care financing that comes directly from government (the columns). The numbers are from 2019—pre-pandemic—and from 26 EU member states (again excluding Malta due to missing data), plus Iceland, Lichtenstein, and Switzerland.

The countries are lumped together into three groups: one group where government pays for a high share of mandatory health care funding, one group with a moderate government share, and one where government plays a marginal role. The results are compelling, with on average a much smaller supply of hospital beds in countries where government is a big funder:

Figure 1

Bluntly speaking: a high rate of government involvement in the permanent (mandatory) funding of health care is a safe way to also ensure the rationing of hospital beds.

This is not just a pandemic-related problem. It has all sorts of consequences for regular health care: with fewer beds come fewer medical professionals. With fewer hands there to provide treatment, patients are faced with health care rationing, including but not limited to serious waiting lists for elective surgery.

It may seem illogical that a high degree of government funding should have these adversarial effects, but the link from the funding model to restraints on health care resources is perfectly understandable. Government needs to balance its budget, and when government is generally a large share of the economy, tax revenue becomes a scarce resource. In response, government holds back the supply of, e.g., health care resources. Hospitals operate at or near full capacity under normal circumstances.

Since government is tied by its fiscal obligations, and since government crowds out private funding, a pandemic rapidly becomes a problem. Hospitals cannot respond adequately, and with inpatient treatment in short supply, the disease in question spreads more easily throughout society.

What can we do about this? Should we simply follow the strict libertarian route and remove government entirely from the health care sector? No, we should not. Government can play an important role in the funding of medical services, one that is consistent with a socially conservative principle of last-resort safety nets (instead of today’s very large welfare states). Social conservatism relies on government to provide a very basic, yet dignified set of benefits for those who cannot provide for themselves.

This role is also compatible with giving government the responsibility to provide resources for health care under exceptional circumstances. The 2020 pandemic would qualify as such.

The point is to get government out of the regular funding of health care. In its absence, medical professionals and private providers can allocate and grow the health care system under dynamic conditions, in direct response to patient needs, changes in medical technology, and other factors that are independent of the often politicized preferences that guide government funding.

If we can shift health care funding away from government and onto social insurance programs, private insurance, and voluntary models, our health systems will be a lot more resilient when the next pandemic comes. Hopefully, this means that governments will be far less inclined to resort to draconian restrictions on the freedom of their citizens.