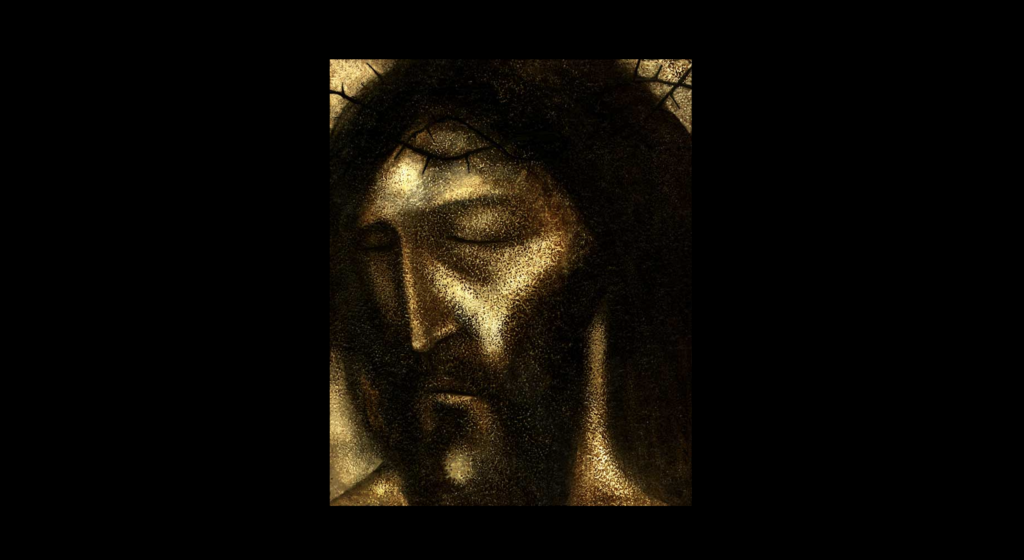

“Ecce Homo,” painting by Michael D. O’Brien, courtesy of Our Lady Seat of Wisdom College.

The work of Dalmacio Negro Pavón reveals that politics cannot be understood without anthropology: the various conceptions of humanity throughout history are not mere theories but paradigms that have shaped the lives of peoples and conditioned political thought.

In 1996, Michael D. O’Brien had his literary breakthrough with the apocalyptic thriller, Father Elijah. The protagonist is the Jewish convert and Carmelite monk, Father Elijah, formerly David Schäfer. In the novel, we follow him on his journey toward a confrontation with the Antichrist, the president of the European Union, who seems, to the general public, to be a cultivated, respectable person promoting world peace. After their first, inconclusive rendezvous on Capri, the final confrontation is to take place in Jerusalem. Depicting Fr. Elijah and his friend the Carmelite friar Enoch, walking toward Jerusalem, the last paragraph identifies them with the Two Witnesses in the Book of Revelation: a cliffhanger ending which anticipates an apocalyptic final battle in the sequel. Instead, however, O’Brien wrote a prequel which focused on Fr. Elijah’s childhood in the Warsaw ghetto. And, after two other titles with end-times plots set in Canada, O’Brien turned to other themes and settings: the Russia of The Father’s Tale and the Croatia of Island of the World. So the apocalypse was suspended until 2015, when O’Brien published the sequel, Elijah in Jerusalem.

Elijah in Jerusalem describes how Fr. Elijah and Br. Enoch arrive in Jerusalem on their mission to confront the Antichrist and unmask him to the public. In the previous confrontation on Capri, Fr. Elijah had resorted to exorcism to give the president a chance of choosing between good and evil. For this new public face-off, rather than physical violence, he adopts once again the strategy of exorcism, not to give the president a second chance but to expose publically his true identity and purpose. Fr. Elijah’s mission, however, is constantly frustrated. Traveling throughout the Middle East to solve the ongoing conflict, the president proves elusive. Indeed, as the embodiment of globalizing Western modernity (similar to the Antichrist of Robert Hugh Benson’s 1907 novel, Lord of the World), his peace achievements earn him heroic, even messianic, status.

Thus, the high drama that powered the first novel takes a back seat, and the larger part of the novel consists of a series of minor stories in which Fr. Elijah meets different persons and acts as a catalyst in their life crises, allowing them, as he had the president, a fresh choice between good and evil. But the actual moral decisions are mostly left outside the narrative frame; the outcome is undecided. Fr. Elijah also stays at a place called the House of Reconciliation in Ramallah on the West Bank, which welcomes Christians from different parts of the world, providing refuge and spiritual retreat. It is a small cosmopolitan community of sincere Christians living in material simplicity, and it functions as a symbol of what the larger Church ought to be, according to O’Brien.

The actual confrontation with the Antichrist takes place only towards the end of the novel, at an interreligious prayer-meeting in front of the Wailing Wall, and it is a total failure. Security guards kill Br. Enoch, while Fr. Elijah is critically wounded and taken to a detention center, where he is tortured as a terrorist.

After being released, thanks to old contacts in the Israeli security services, he lies in bed, in the House of Reconciliation, and senses that death is approaching. He realizes that he and Br. Enoch had been mistaken; they were not the Two Witnesses. Everything seems futile and hopeless. In this situation, he dimly sees two people standing by his bedside, and they begin to speak with him. It becomes clear that they are the Two Witnesses, and that they will finish what Elijah and Enoch had begun.

In a sense, this is another cliffhanger: the decisive confrontation with evil is postponed to the near but indefinite future. Fr. Elijah’s life has a seemingly tragic dimension, driven by divine command to what appears to be a failed mission, and his own death. The novel explicitly connects this failure to that of the cross, but the narrative does not include Fr. Elijah resurrected, or the battle won. The successful conclusion takes place outside the story. An earlier passage in the novel makes this clear:

Yet he also knew that the mission was not so much about success but about whether he stood firm in obedience. It was the cross, rooted in the dust of the earth, watered by the blood of God’s servants, the sign pointing to heaven, soaring upward into pure light.

In Christian Theology and Tragedy: Theologians, Tragic Literature and Tragic Theory, Kevin Taylor and Giles Waller make a case for a common ground between theology and tragedy. They begin with downplaying what they call caricatures of the two. Christian theology is not naïve, bland optimism and escapism, and tragedy is not all nihilism. They want to show that there is a shared area of “experience of suffering, death and loss, questions over fate, freedom and agency, sacrifice, guilt, innocence, the limits of human understanding, redemption and catharsis.” They continue, “we might press this even further, and maintain … that an attentiveness to tragedy is vital for a disciplined Christian theology.”

According to Kevin Taylor, systematic theology and philosophy need to acknowledge the existential mystery of evil.

One of the insights of literature, and particularly tragedy, is the mysteriousness of human suffering. A deficiency of systematic theology, as a conceptual and rational discipline, is its tendency to dispel the ineffable nature of suffering by framing it within a larger epic.

But if the tragic dimension of suffering is precisely this lack of meaning, and represents an inadequacy in theodicy, what to make of Christian hope? And how does this affect the literary imagination of a sincere Christian? In O’Brien’s novels, a central motif is the horror of the Holocaust and similar totalitarian forms of radical evil during the 20th century. They are, however, not merely historical events for him but reminders of what might emerge at any time. Worldly optimism is therefore not an option for O’Brien, but he still emphasizes the reality and importance of hope, as a supernatural gift from God.

Personal suffering is pervasive in O’Brien’s novels, and it is mostly portrayed as an emptying out of the individual. The protagonist has to set out on a journey alone, separating himself from his social context, material possessions, and self-esteem—as, for example, in the novel, Strangers and Sojourners, in which, after his departure from home, the hero suffers a series of misfortunes which gradually remove the little he has gained on the journey.

It is as if, in peeling away layer after layer from the individual, O’Brien is testing whether he can reach an essence, the nucleus of real personality. In modern, secular terms, this would correspond to the search for the true self, the center of personal autonomy, behind the surface of social roles and masks. In O’Brien, however, the process is more akin to a Christian kenosis: an act of self-emptying, in order to be filled with the Divine will.

For O’Brien the gradual deprivation of the sojourner is also connected to the Franciscan ideal of poverty; in his diary he often writes that material possessions are hindrances to achieving a state of spiritual purity and dedication. Suffering purifies a person and turns him toward the supernatural, ideal pole of life. But, at the same time, it can invite discouragement, a sense of individual failure, of having misunderstood one’s mission: the “why have you forsaken me?” on the cross.

But there is also the sense of collective failure. From O’Brien’s perspective, Christian civilization and the Church are failing in critical ways, inducing a sense of collective kenosis, and the temptation to social despair. The raw pain of collective suffering puts supernatural hope to the test. The tragic element in Elijah in Jerusalem lies in its earthly expectations which, fragile at best, compromise the Christian search for temporal solutions, the desire to build a better civilization. Instead, hope is firmly directed toward a spiritual reality.

O’Brien, therefore, does not propose in his novels a retreat from modern life to alternative communities—although the House of Reconciliation offers at least a temporary refuge from the persecutions of a godless modernity. Elijah and Enoch’s tragic misunderstanding of their vocation, and the subsequent sense of failure, means that the novel places the reader under the cross with John and Mary, knowing that death and entombment will follow, but still in the dark about the resurrection.

If the first Father Elijah novel mirrored the apocalyptic expectations of some Christian groups in the 1990s, moving toward the end of the second millennium, the sequel struggles with failed eschatological expectations and what, instead, looks more like a slow loss of vital energies on the part of Christianity. It was also written in maturity, when, typically, collective judgment ceases to be the most pressing concern, and gives way to the not-so-distant personal meeting with the Creator. One must then face troubling questions, such as: have my life’s struggles for the good, even the holy, actually changed very little? Were they in harmony with the common good, or God’s plan, or merely expressions of my will? Over nineteen years and two novels, Fr. Elijah changed from a classic hero to a victim crushed under the juggernaut wheels of modern civilization. Still, even if O’Brien does not incarnate the resurrection in the plot, in the shape of achieved goals, the message of hope remains in the appearance of the Two Witnesses at the novel’s end:

Both men stretched forth their arms and laid their hands on his head. “Be at peace, beloved servant. The victory is near.” Peace entered him with their touch. He closed his eyes again and slept.

The O’Brien novels published after 2015, such as The Fool of New York (2016) and The Lighthouse (2020), strike a more serene tone and do not so insistently probe the tension between the cross and the sense of tragedy. They revolve around the protagonist coming to an understanding of himself, and a resolution of past traumas. Although The Sabbatical (2021) returns to the struggle with evil, and considers the formation of an alternative, underground civilization, they remain marginal ideas.

O’Brien’s oeuvre shows the “ineffable nature of suffering,” as embodied by the gritty reality of Good Friday, and the long wait of Holy Saturday. His vision is not of a rejuvenation of Christendom as a political entity, but is similar to the expectation of the early martyrs. In this way, realism and supernaturalism intermingle in his novels. They contain both caution and encouragement to sincere Christians living through the de-Christianization of the Western world.