Sweden faces a macroeconomic meltdown that could even exceed the Greek austerity crisis from a decade ago. There is no public debate about it, certainly not in Swedish media.

There is a reason for this. Swedes have an image of their country as being the pinnacle of prosperity, peace, and thoughtful policy making. In reality, their economy is a balloon inflated by excessive private debt and deeply rooted structural weaknesses. What is coming down the pike is a self-inflicted crisis, the fallout from catastrophic political group-think.

Three decades of debilitating fiscal policies, purposely designed to inflate one of the world’s largest and most unsustainable welfare states, are about to boomerang right back at those who created those policies. This new crisis could very well overshadow the one from the early 1990s.

Back then, Sweden went almost overnight from full employment to an unemployment rate in excess of 15%. Gross domestic product, GDP, declined for three years in a row. From 1990 to 1993, business investments fell by 26% in real terms.

There are several reasons to expect a more serious crisis this time, one being the intellectual bubble problem. Politicians refuse to understand that their selfish government-first policies actually harm the economy. In addition, the country has an incompetent cadre of economists where agreement, rather than debate, is considered the path to thoughtful scholarly conclusions.

When think-alike economists advise government-first politicians, the outcome is always going to be bad. As I explain in Industrial Poverty, the unison response from Swedish economists and politicians to the ’90s crisis was to protect the welfare state at all cost. Higher taxes and crippling austerity policies equal to 7% of GDP, permanently raised the cost of government to both businesses and households. Meanwhile, government provided inferior services and weaker benefits.

Taxes in Sweden consistently claim half of the economy, making it one of the highest-taxed countries in the European Union. Together with the spending cuts from the 1990s, these taxes have forced people to pay more for less. In response, they have to find alternative ways to provide for themselves what government used to provide. They have had to do this out of paychecks that are already heavily crippled by those high taxes.

Needless to say, the fallout is a stagnant standard of living for Swedish households. The only way they have moved forward, or at least stayed afloat, is by means of massive indebtedness. Their growing debt burden has primarily funded home purchases, but that does not make the debt burden any better. The debt has been necessary because regular incomes have not been enough for Swedish families to maintain a regular European standard of living.

There are recent signs that not even massive borrowing can maintain that standard anymore. Over the past 25 years, Swedish consumer spending has slowly drifted toward stagnation. According to Eurostat, from 1996 to 2000, household outlays increased by an inflation-adjusted 3.5% per year. Since 2003, the growth rate has declined: measured as five-year moving averages (due to high year-to-year volatility), in 2010 it was down to 2.6% per year; in 2015 it had dropped to 2.3%.

In 2018 and 2019, the last two years before the pandemic, the average annual growth rates were 1.9% and 0.8%, respectively.

While stagnation sets in, debt keeps growing. According to the OECD, in 1996, Swedish households had a debt equal to 94% of their after-tax disposable income. That ratio had increased to 154% in 2006 and 183% in 2016.

In 2021, Swedish households had amassed a debt equal to 203% of their disposable income. Figure 1 puts this trend of rising debt in a context; the blue line is the Swedish debt trend:

Figure 1

Low interest rates have helped Swedish households take on more debt. They were not alone in enjoying cheaper credit: statistics on the yields on long-term government securities (from Eurostat and ECB) show that by 2015, a dozen countries in Europe had rates below 1%.

Interest rates on government securities do not directly affect interest rates on consumer credit, but they are good indicators of the overall trend in the cost of credit in an economy. Since government securities are generally considered risk free, investors who are adverse to risk will demand a higher return on riskier assets; government debt instruments are typically the benchmark for risk-premium calculations.

Both the yield on government debt and the rates that consumers pay on bank loans are linked to the supply of liquidity (money, broadly speaking) in the economy. That supply increased dramatically in the 2010s, in both Europe and North America. As a result, all kinds of interest rates plummeted, often to record lows.

In Sweden, the result was a continuously rising household-debt ratio. Some other countries saw the same trend, including Canada, Finland, France, Norway, and Switzerland, but it was at least as common that the upward trend turned downward, as per Figure 1.

A rising debt ratio is not in itself a recipe for a crisis, but when it correlates with stagnant consumer spending, we have a structural problem in the economy. It means that debt is becoming a regular source of funding regular spending.

To find out to what extent this is a problem in Sweden, I calculated the ratio of debt-growth consumer spending, i.e., the amount of new debt that households assumed per €100 (or national currency) of private consumption. The results are striking. Since 2013, Swedish households have on average taken on new debt, equivalent to 26% of their consumer spending every year.

In 2021, that ratio reached 42.7%. Sweden has the second highest average ratio for 2013-2021 of all the 22 countries in Europe for which the OECD consistently reports household debt. Only Luxembourg has a higher ratio, and that is not exactly a badge of honor for the Swedes, as Luxembourg is an extreme case given its tiny size and socio-economic composition.

As noted earlier, it does not matter that a significant portion of Swedish household debt consists of mortgages: fast growth in debt relative to private consumption is still a signal that households are struggling with an unaffordable standard of living. As Figure 1 shows, households in, e.g., America and Hungary have been able to reduce their debt-to-income ratios.

And now for the bombshell. Following the lead of other central banks, the Swedish Riksbank has raised its lead interest rate in four steps in 2022, from zero to 2.5%.

We know from the ratio of new debt to private consumption that Swedish households generally have small margins in their finances. Even the Riksbank’s modest rate hikes will have dramatic effects on the economy.

According to the Swedish statistical agency SCB’s official index of prices and sales volumes for single-family homes, the number of home sales in November was a whopping 65.7% lower than in the same month in 2021. The total value of home sales declined from SEK19.6 billion (€1.74 billion) per month to SEK6.6 billion (€587 million) per month.

This is not a decline—it is an implosion. Even more worrisome is that the average sales price has only fallen by 1.7%. This tells us that the large majority of homeowners who need to put their house on the market decide not to do so. They are stuck in homes where they risk being left with unpaid mortgage debt if they sell.

A similar trend is underway in the market for owner apartments (mostly co-ops; there are very few condominiums in Sweden). Taken together, these two real-estate markets represent a grave threat to the Swedish banking sector: approximately 49% of their assets consist of loans to households and mortgage intermediaries.

Banks are getting worried. In October, lending to households dropped by 28% on a year-to-year basis. This is far more serious than anything the Swedish economy experienced during the Great Recession in 2009-2011. It is beginning to look like the crisis from 30 years ago.

The only problem is that the macroeconomic foundation is worse today. A crisis of the ’90s magnitude could very well turn into something greater. One of the reasons for this is that Sweden is going into this new crisis with a weak labor market—when the ’90s crisis broke out, the Swedish labor market was operating at maximum capacity.

That is not the case today. Employment is lower, unemployment is among the highest in Europe, and labor productivity is unimpressive. Not only does this make the economy weaker going into the crisis, but it also means that the crisis itself can start earlier and become more violent than would otherwise be the case.

The reason is in the relation between labor earnings and household debt. A loan is paid back out of current income, which normally comes from employment. Therefore, the ability of an economy as a whole to handle high debt ratios depends on the rate of employment and on labor productivity. The former guarantees that there is an income in the first place; the latter is the driver of growth in that income.

In other words, when the economy is operating at full employment, workers can, with relative ease, develop their careers and make more money. They can also find a new job if they are laid off. By contrast, when employment is low, even small aberrations in work hours or wages and salaries can put a family in a financial hole.

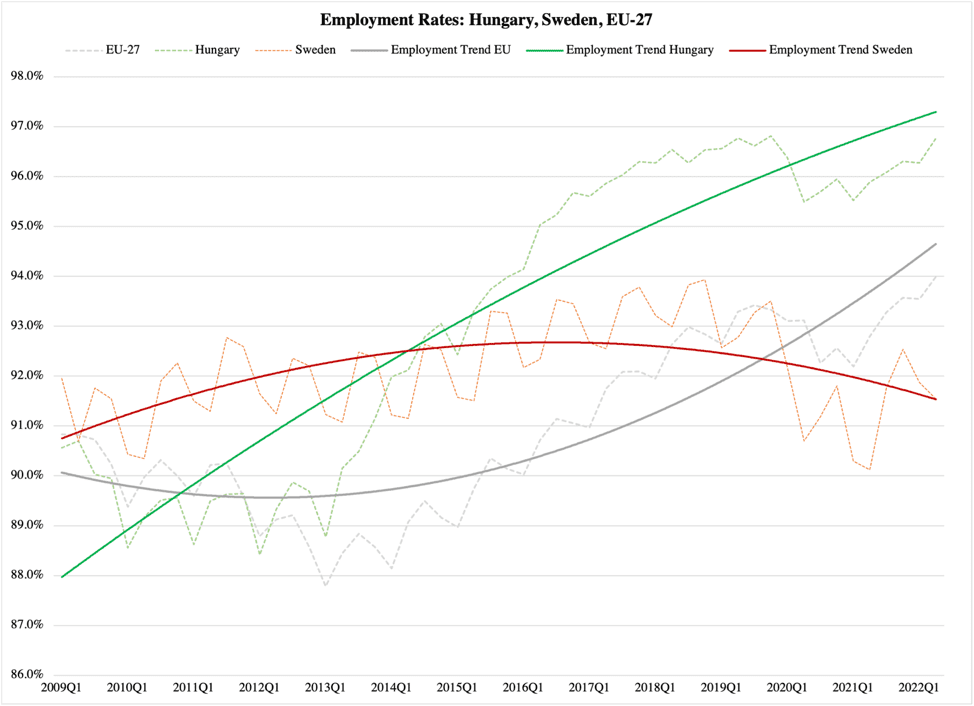

Sweden is in the latter category. The red function in Figure 2 below reports the employment rate in Sweden, i.e., the rate of the workforce that has a job. The same rate for Hungary—one of Europe’s strongest economies—is green, and the European Union as a whole is displayed by the gray function. While the latter two have seen the employment rate rise in recent years, Sweden reached a peak in 2017 and has since experienced a drop:

Figure 2

The comparison to Hungary is compelling. Unlike Sweden, the Hungarian government has consistently focused its fiscal policy on promoting economic growth. A smart tax reform in 2016 made life easier for businesses, especially the smallest ones. With one of Europe’s lowest corporate-tax rates (ostensibly the lowest under the 15% unionwide model) Hungary has become a magnet for foreign direct investment.

Since the Swedes have done none of this, it should come as no surprise that the Hungarian employment rate is a rocket ship, while the Swedish one looks like a falling firecracker.

To be fair, the decline in the Swedish employment rate since 2017 is not catastrophic, but it means that households in general have smaller margins than in the rest of the EU when it comes to maintaining, let alone improving, their wages and salaries. This creates a structural weakness in the economy, given the rising level of household debt.

Or, to refer back to the rising interest rate: where stronger and more resilient economies could absorb higher rate hikes, Sweden is beginning to feel the pinch already at a modest central-bank rate level of 2.5%.

Labor productivity does not help either. Figure 3 compares labor productivity in Sweden and, again, Hungary, on a quarterly basis: green columns indicate quarters when the Hungarian workforce improved its productivity relative to their peers in Sweden, and blue columns indicate the opposite:

Figure 3

A weaker trend in labor productivity means weaker business interest in investing in the future. If taxes are high on top of that, the case against Sweden grows stronger. On top of that, weak productivity leads to stagnant wages.

Which, in turn, speeds up the process that brings the economy to a point where debt defaults become a systemic threat.

Swedish politicians and economists made many errors 30 years ago. Those errors structurally strengthened government and weakened the private sector. Cheap credit concealed the real cost of those errors.

No more. The chickens are coming home to roost.