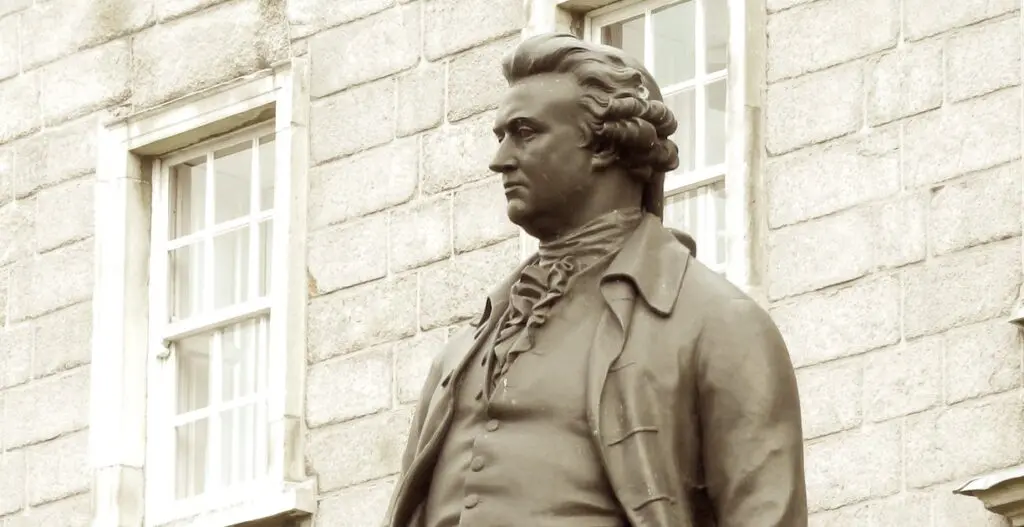

Whatever their disagreements, the National Conservative “Statement of Principles” and the post-liberal retort criticising it, which was published some months ago, agreed on paying deference to the figure of Edmund Burke.

In addressing the limits of conservatism, therefore, Burke provides us with a useful case study, not only because he continues to receive a kind of reflexive allegiance—but because this allegiance is not just rhetorical. His shortcomings really do endure in the paradigms conservatives operate within to this day.

Like his equivalents in other countries, Burke failed the test of his era’s truly conservative, and therefore, truly radical, struggle: saving and updating the commons as locus of virtuous sociability and the production and preservation of identity. By “the commons” is meant common land (and other resources) subsequently enclosed, where ‘enclosure’ refers to

The division or consolidation of communal fields, meadows, pastures, and other arable lands in western Europe into the carefully delineated and individually owned and managed farm plots of modern times … To enclose land was to put a hedge or fence around a portion of this open land and thus prevent the exercise of common grazing and other rights over it.

The modern political Right is, if anything, more blind, because more removed, from the historical and possible future significance of the commons. I’ve written on this before, and hope that more conservatives come to view it as essential to their project.

In his 1795 Thoughts and Details on Scarcity, Burke argued that

A greater and more ruinous mistake cannot be fallen into, than that the trades of agriculture and grazing can be conducted upon any other than the common principles of commerce.

Therefore, he continued,

The producer should be permitted, and even expected, to look to all possible profit, which, without fraud or violence, he can make; to turn plenty or scarcity to the best advantage he can; to keep back or to bring forward his commodities at his pleasure; to account to no one for his stock or for his gain.

Because,

On any other terms he is the slave of the consumer; and that he should be so is of no benefit to the consumer.

In fact, as Canadian historian James Eayrs opined with regards to this passage, its sentiments “could hardly be more opposed to the traditional view of the responsibilities of landownership.”

In The Conservative Mind, Russell Kirk admitted that,

It is one of the few charges that can be preferred successfully against Burke’s prescience… that he seems to have ignored economic influences spelling death for the eighteenth-century milieu quite as surely as the Social Contract [theory] repudiated the eighteenth-century mind. He was thoroughly acquainted with the science of political economy: according to Mackintosh, Adam Smith himself told Burke, “after they had conversed on subjects of political economy, that he was the only man, who, without communication, thought on these topics exactly as he did.”

This should prick the ears of anyone suspicious of Smith’s idea that individual interest maximizing accrues (alchemizes) into collective prosperity and public virtue (although we should note that, among other issues we will address, Burke and Smith disagreed on the question of primogeniture, and this for quite significant reasons).

Kirk continues:

But what is one to say about Burke’s silence upon the decay of British rural society? Innovation (as Burke, and Jefferson, knew) comes from the cities, where man uprooted seeks to piece together a new world; conservatism always has had its most loyal adherents in the country, where man is slow to break with the old ways that link him with his God in the infinity above and with his father in the grave at his feet. Even while Burke was defending the stolidity of cattle under the English oaks, wholesale enclosures, the source of much of the Whig magnates’ power, were decimating the body of yeomen, cotters, rural dwellers of every humble description; as the free peasantry shrank in numbers, the political influence of landowners was certain to dwindle. “To what ultimate extent it may be wise, or practicable, to push enclosures of common and waste lands,” wrote Burke, “may be a question of doubt, in some points of view; but no person thinks them already carried to excess.” His misgivings went no further.

Of course, there is no contradiction between Burke’s “silence upon the decay of British rural society,” on the one hand, and his thorough acquaintance “with the science [sic] of political economy” (to the point of thinking “exactly” as Smith did on certain of its postulates) on the other. The latter is confirmed by his remarks in “Thoughts and Details on Scarcity,” and the former provides the basis for our suggestion that Burkean conservatism’s allegiance is principally to economic liberalism, not to the preservation of social arrangements conducive to human flourishing.

In his excellent “The Un-Burkean Economic Policy of Edmund Burke,” Geneva College professor emeritus of economics Ralph E. Ancil observes how Burke fails to participate in that “recognition of the important role of small landed proprietors” of some of his contemporaries, which was to endure “throughout the 19th century:”

If Burke were worried that… England, too, would suffer the fate of the French, he could not have done better than to undertake appropriate intervention to see that small, landed proprietorships flourished… However, Burke did just the opposite because he failed to distinguish between a healthy, functioning hierarchy and an exploitative elite.

Burke’s diagnosis of the causes of the French Revolution was premised on the idea that

The ruling class and large landed estates naturally go together and provide a wholesome social safeguard. And this has been true since ancient times. He refers to Aristotle as one “who observes that the agricultural class of all others is the least inclined to sedition.” So also in England, the “landed interest” has been that class which “has at all times been in close connection and union with the other great interests of the country, [and which] has been spontaneously allowed to lead and direct and moderate all the rest.”

(The passages quoted here are from Burke’s Letters on a Regicide Peace).

Crucially, then,

For Burke, “landed property” is not the small peasant proprietorships which Aristotle refers to that have a significant share in government, and a wide distribution of productive property, essential to the “best kind of democracy.” Instead, his view of distributive justice entails an elite endowed with large concentrations of land and largely inherited duties and privileges.

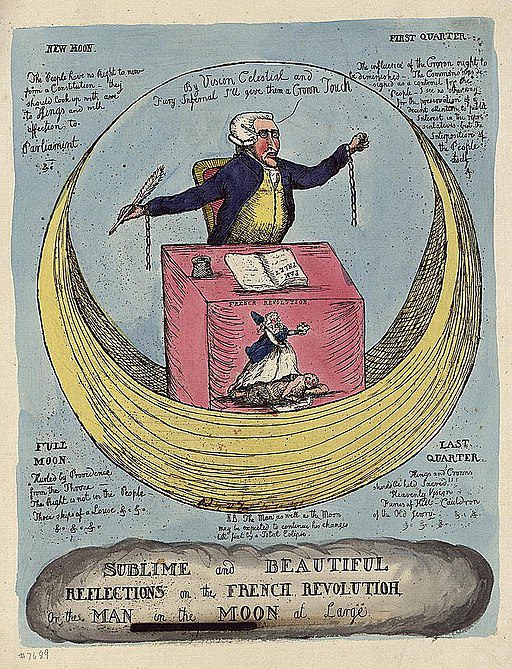

The defence of such property goes quite far in Burke. In Reflections on the French Revolution he writes that (my italics):

Nothing is a due and adequate representation of a state, that does not represent its ability, as well as its property. But as ability is a vigorous and active principle, and as property is sluggish, inert, and timid, it never can be safe from the invasions of ability, unless it be, out of all proportion, predominant in the representation. It must be represented too in great masses of accumulation, or it is not rightly protected. The characteristic essence of property, formed out of the combined principles of its acquisition and conservation, is to be unequal. The great masses therefore which excite envy, and tempt rapacity, must be put out of the possibility of danger. Then they form a natural rampart about the lesser properties in all their gradations. The same quantity of property, which is by the natural course of things divided among many, has not the same operation.

Ancil comments as follows:

It is almost as if in Burke’s mind large agglomerations of land ownership have a hortatory effect because, being easily seen, they impress the people with respect for property. Masses of accumulation by the few, preferably those of distinguished hereditary property and hereditary birth, are also vital for sound government. Such a group is the house of peers which is, in the last event, “the sole judge of all property in all its subdivisions.” Such a “preference… is neither unnatural, nor unjust, nor impolitic.”

In “Thoughts and Details on Scarcity,” Burke also defends the utility of certain monopolies: “Without question, the monopoly of authority is, in every instance and in every degree, an evil; but the monopoly of capital is the contrary. It is a great benefit, and a benefit particularly to the poor.”

But in Reflections on the French Revolution, as we have seen, his argument seems to run deeper. For Burke, the legitimate symbolic function of property appears to be that of inspiring distance, grandeur and awe, requiring that it not be participated in by the majority of people. It is worth considering the degree to which this species of “conservatism” is of a piece with a kind of scholastic, theological loss of the participative metaphysics and experiential spirituality we find in the work of, for example, Pseudo-Dionysius.

For an alternative, grand-yet-participatory, understanding of this psychological function of property, we might turn to Simon Weil’s The Need for Roots. She writes of the importance of “participation in collective possessions—a participation consisting not in any material enjoyment, but in a feeling of ownership”:

It is more a question of a state of mind than of any legal formula. Where a real civic life exists, each one feels he has a personal ownership in the public monuments, gardens, ceremonial pomp and circumstance; and a display of sumptuousness, in which nearly all human beings seek fulfilment, is in this way placed within the reach of even the poorest. But it isn’t just the State which ought to provide this satisfaction; it is every sort of collectivity in turn. A great modern factory is a waste from the point of view of the need of property; for it is unable to provide either the workers, or the manager who is paid his salary by the board of directors, or the members of the board who never visit it, or the shareholders who are unaware of its existence, with the least satisfaction in connection with this need.

Importantly, she concludes these reflections by rejecting pure (economic or power-political) utilitarianism in accruing property:

When methods of exchange and acquisition are such as to involve a waste of material and moral foods, it is time they were transformed… Any form of possession which doesn’t satisfy somebody’s need of private or collective property can reasonably be regarded as useless. That does not mean that it is necessary to transfer it to the State; but rather to try and turn it into some genuine form of property.

Returning to the deficiency of Burke’s approach, we find Ancil agreeing with German economist Wilhelm Roepke’s opinion that, if anything, the conservative icon’s defence of property concentration “contributed to the proletarianization in England which… helped produce the very ‘revolutionary’ results he so feared: the egalitarianism, the secularism, the entire levelling tendency which is evidenced in the 19th and 20th centuries of Great Britain.”

Ancil summarizes the point:

Burke’s … Thoughts and Details on Scarcity is his most complete view of economic theory and policy. It is not ambiguous but clear and firm, and, as argued here, is inconsistent with his better insights elsewhere. He allowed his fear of the French Revolution to cloud his judgement of a fitting response to the needs of agricultural workers… He was blind to the dangers of monopoly and concentration of economic power, to the possible ways of intervening that conform to the character of a market economy, to the need to preserve economic independence through the widespread possession of economically productive assets which, at the time, meant land, to the fruitful history of the English tradition whose relevant policies were amenable to reform and improvement to suit new conditions but were, instead, dismissed wholesale in the name, ostensibly, of an abstract economic theory… How much better it would have been had he worked for economic policies that assured property, as well as fair wages, for the English worker.

Be it in the context of that level of property-concentration favoured by Smith or Burke, then, the land-owner is to act according to the rules of “the market.” For Burke, as for Smith, “the producer should be permitted, and even expected, to look to all possible profit… to account to no one for his stock or for his gain.” Burke’s remarks clearly assume ownership of a sort quite removed from that of village-level holdings and their traditional use of commons.

In this regard, Burke’s support for concentrating land ownership should not be balanced against Smith’s, but replaced wholesale with G.K. Chesterton’s reflections on this point. Chesterton argued that the problem with capitalism was not too much capitalism, but too few capitalists (owners of productive capital), also characterizing economic determinism as

The mystical dogma of Bentham and Adam Smith and the rest, that some of the worst of human passions would turn out to be all for the best. It was the mysterious doctrine that selfishness would do the work of unselfishness.

As for the incongruence in Burke’s attitudes which Kirk highlights, and which constitutes his agreement with Smith, this is the very basis of those denaturing social processes in the wake of which we still live, and about which much conservatism is so thoroughly ambiguous. Karl Polanyi writes the following in The Great Transformation:

What made economic liberalism an irresistible force was this congruence of opinion between diametrically opposed outlooks; for what the ultra-reformer Bentham and the ultra-traditionalist Burke equally approved of automatically took on the character of self-evidence.

Concerning two principle variants of British (and North American) political thought destined to inspire contending electoral factions over several centuries, I tend to agree with Thompson’s assessment in The Making of the English Working Class, when he writes of their (apparently opposed) luminaries, Burke and Thomas Paine. “In the 1790s,” observes Thompson, “the ambiguities of Locke seem to fall into two halves, one Burke, the other Paine:”

If Tom Paine was wrong to dismiss Burke’s cautions … he was right to expose the inertia of class interests which underlay his special pleading. Academic judgement has dealt strangely with the two men. Burke’s reputation as a political philosopher has been inflated, very much so in recent years …. In truth, neither writer was systematic enough to rank as a major political theorist. Both were publicists of genius, both are less remarkable for what they say than for the tone in which it is said … the popular mind remembers Burke less for his insight than for his epochal indiscretion—“the swinish multitude.”

We may now turn to that social transformation Burke conspicuously failed to resist, and, in fact, to a great extent justified (through works discussed by Thompson).

The 1799 General View of the Agriculture of the County of Lincoln, written by a gentleman called Arthur Young, provides an excellent example of the literature of apologia around enclosures and attendant policies:

I know nothing better calculated to fill a country with barbarians ready for any mischief… than extensive commons and divine service only once a month… Do French principles make so slow a progress, that you should lend them such helping hands?

Indeed, according to Young, “everyone but an idiot knows that the lower classes must be kept poor, or they will never be industrious.”

One could hardly imagine a clearer rejection of “the commons,” and this in the name of the values of work ethic (“divine service”) and patriotism (in competing with the French). As an aside, tt is interesting to note that here, as in Burke, the dangers of the French Revolution are not exclusively related to excessive statism and centralization, but with its many ideological affluents, including quasi-medievalist defences of the commons and what we would now describe as non-statist socialism.

The following passage in a late issue of the ‘Commercial and Agricultural Magazine’ published in 1800 expresses similar concerns when it addresses the policy of “permitting the labouring man to acquire a certain portion of land:”

By this indulgence the poor-rates must be speedily diminished; since a quarter of an acre of garden-ground will go a great way towards rendering the peasant independent of any assistance. However, in this beneficent intention moderation must be observed, or we may chance to transform the labourer into a petty farmer; from the most beneficial to the most useless of all the applications of industry. When a labourer becomes possessed of more land … the farmer can no longer depend on him for constant work, and the hay-making and harvest … must suffer to a degree which … would … prove a national inconvenience.

There is not much separating the above recommended “moderation” from the conclusion that getting people off their land will increase the supply of salaried workers and thus prove the opposite of “a national inconvenience,” being quite convenient so far as gross domestic production is concerned. (Again, for an exploration of these and related sources, see E.P. Thompson’s The Making of the English Working Class.)

The sentiments animating Arthur Young’s reflections and those of the “Commercial and Agricultural Magazine” still inspire sectors of the Right today, poisoning their fight against the post-modern Left with dehumanizing utilitarianism. Even those most inclined to reject the Anglo-American tradition will often oppose its economic determinism and “free market” rhetoric with blandly reactionary statism (conservative versions of nudge economics and the like).

Obviously, this is not to argue that the state should refrain from top-down incentivizing of certain behaviours, but conservatism must produce social structures and practices that perpetuate it endogenously, bottom-up (by their own internal logic): communities whose functioning requires, or is optimized by, those practices which are of a piece with physical, psychic, and spiritual health. Otherwise, rather than going beyond liberalism, conservatism will succeed only in being anti-liberal; just one half of modernity’s dialectic between atomized individual and denaturing collective.

It is here that I would argue for a restored, politically-empowered commons, intelligently integrating modern technology, as the centrepiece of any conservative project worthy of the name. It is not the case, for example, that the opposite of Burke’s attitude towards the farmer and his commercial interests, is a state forcing him to produce food and sell at a price pegged to its projections. Rather, land ownership and exploitation (including food production and the compensation therefore) can, in part, be integrated into what political economist Elinor Ostrom described as the “design principles” of successful Common Pool Resource (CPR) management.

Ostrom’s work exposes the lie that communities must necessarily be fed to one of the heads of Cerberus, Market or State, or, as she puts it in Governing the Commons, the “Leviathan as the ‘only’ way” vs. “Privatization as the ‘only’ way” paradigm (I would add that this book is excellent except where it tries to outline historical causes for the rise of certain institutions, in which context Ostrom is clearly out of her element).

Her findings, and those of other researchers in the same vein, deserve their own, separate exploration, as do the consequences of that state-sponsored dissolution of the commons that swept over Europe in the early modern period, a reaction against which could be said to have pulsed in the background of certain traditionalist movements, such as Spain’s Carlismo, as well as currents of non-Marxist socialism. In particular, in a future essay I plan to address how a proper understanding of the commons should inform our concept of nationhood.

To conclude the above, however, I will simply reiterate the need to break with sterile dialectics (atomized individual vs. undifferentiated collective; economic liberalism vs. social liberalism; private oligopoly vs. state monopoly) and look to a more genuine, more radical, conservatism, able to cut across established categories with its transversal appeal to traditionally Left-wing values.