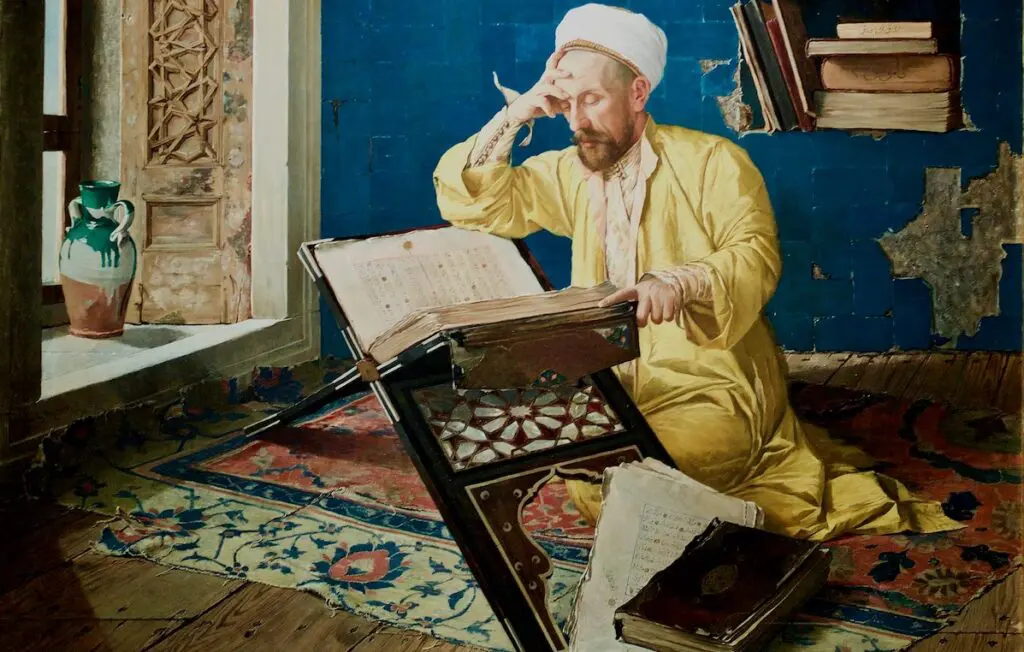

“Meditating on the Koran” (1902), a 145 × 171 cm oil on canvas by Osman Hamdi Bey (1842-1910).

Islam has been reduced to one of the identities that constitute a ‘hierarchy of victimhood.’ Joined with race, sexuality, and gender, it has been forced into a ‘woke’ framework wherein any community or group that stands outside the West’s traditional boundaries is structurally disadvantaged. The Leftist activists who preach this narrative have been joined in an uneasy alliance by Islamic fundamentalists, bonded with one another by a deep hatred for the Western world. Both regularly decry any critique of Islam as pure acts of bigoted ‘Islamophobia,’ proof positive of the West’s supremacist posture. This is characterized as an attempt to protect a beleaguered religion from malicious discrimination. However, the push to classify Islam as pure ‘victim’ essentially strips it of its civilizational tradition—one which has allowed for challenge, disagreement, and dialogue—infantilizing it to indulge in a resentful rejection of the West.

Taken realistically, there are a myriad of concerns that arise when one considers the future of Islam in the West. Can we reconcile the religious traditions that serve as the basis for our respective worlds? Can the distinctions between our understanding of religion’s political role be resolved? What about the status of women or the freedoms of speech, religion, and conscience that stand as hallmarks of Western society? How can we negotiate explosive and sometimes lethal responses to blasphemy, which, as offensive as it may be, falls under the umbrella of a liberty that we treasure in the West?

Rather than recognize the religious, cultural, and civilizational differences that contribute to the alienation of Muslim communities in the West, these tensions are attributed to deeply ingrained ‘intolerance’ within host countries. However, it is necessary to negotiate honestly on the thorny issues surrounding integration. To do otherwise invites not only societal breakdown, but also smacks of a paternalistic ignorance of the magnitude and depth of the tradition we are engaged with. Islam is not the progeny of the ‘woke’ diatribe on power’s exclusive role in shaping our social fabric, nor is it a cog in a hierarchy of victimhood. It is not necessarily a brutal and barbaric totalitarian system, as many Islamists would have us believe. Instead, it is a dynamic and intellectually rich tradition that can be as much admired as it can be scrutinized.

There are strains within Islamic tradition that encourage an openness to dialogue and that allow non-Muslims to call it to account. The insulated attitude of those who claim that it is victimized—be they Muslim activists or their Western ‘defenders’—has not always been the mainstay of the religion. There was a time when the caliphal halls of Baghdad and the universities in Spain and northern Africa were sites of lively debate that would appear wholly foreign in many parts of the Western world today. Perhaps one of the most striking products of this free flow of ideas is the Apology of Al Kindi. Although there is serious scholarly disagreement about its origins and structure, it is generally accepted that it was written by a Christian attendant, Al Kindi of the court of Al-Ma’mun, around 830. (Of note, he is not to be confused with the great Muslim philosopher Al Kindi, who lived around the same time.)

This curious essay was published in response to his Muslim friend, Ibn Ismail, who had invited the Christian to convert. Ibn Ismail asked Al Kindi to respond freely and to lay out his critique of Islam, all with the assurance of protection and the retainment of his status at court:

Bring forward all arguments you wish and say whatever you please and speak your mind freely. Now that you are safe and free to say what you please, appoint some arbitrator who will impartially judge between us and lean only towards the truth and be free from the empery of passion.

Al Kindi accepted the invitation and published a critique of Islam that is shocking to the modern reader. He is blunt in his criticism—and at times arguably too harsh—on questions ranging from the Quran’s confused claims about Christian theology, to the violence of the early conquests, to the promise of earthly success over the more noble Christian emphasis on union with God in the afterlife, to the status of women and sex. Al Kindi went so far as to critique the Prophet Muhammad, because “his chief delights were, by his own confession, sweet scents and women—strange proofs these of the prophetic claim.” One can safely assume that Ismail’s refutation of Christianity was equally biting.

Throughout the work, Al Kindi reiterated the necessity of reasonable men to engage in discourse over matters of import, including—and perhaps especially—faith. “Religion is not one of those matters which men of sense and understanding can restrain from probing and discussing, or neglect to test by right principle,” he wrote. His admonition was met with admiration from his Muslim interlocutor; it is even rumored that the caliph had attendants read him the arguments. Al Kindi did not suffer as a result, and the promise that he was safe to express his disagreement and even disdain for the religion of the royal court was upheld.

This was not an isolated moment in Islamic history. Many great Muslims have argued that it is incumbent upon the faithful to honestly and devotedly search for the truth; to remain open to what can be discovered through study and interchange. A believer is not meant to hide behind a defensive posture of perpetual victimhood but to pursue truth, as uncomfortable as it may be. As a hadith (a saying attributed to Muhammad) says, “The word of wisdom is the lost property of the believer. Wherever he finds it, he is most deserving of it.”

It was in the spirit of this hadith that Averroes, the philosopher that Aquinas identified as the “commentator” throughout the Summa, wrote his Decisive Treatise. In it, he outlines his argument, drawing from Quranic exegesis and hadith tradition, that the Muslim is called to open himself up to the world as it is and humbly submit to what he finds, regardless of the source. This will not only lead him to a deeper knowledge of creation, but also of the creator:

The activity of philosophy is nothing more than the reflection upon existing things and consideration of them … is an indication of the Artisan … The more complete the cognizance of the are in them is, the more complete is the cognizance of the Artisan.

Averroes makes this assertion not merely to fulfill the demands of philosophical inquiry, but as a matter of the aims of Islamic law itself. The central role that revelation plays as a form of law, in the structure of both public and private life, shows how integral Averroes thought these demands were to authentic belief. It was not merely a question of man as the kind of thing that naturally seeks to know the world; instead, Averroes thought that within the revelation which gave rise to his civilization, God commanded that reason be aimed towards understanding: “The Law has recommended and urged consideration of existing things,” the practice of which Averroes identified as philosophy.

Averroes does not restrict the direction of inquiry into that which is either theologically relevant or dogmatically accepted. According to Averroes, the scope of the Muslim’s consideration should fearlessly encompass all that can be known. This, by necessity, includes those truths which are discovered and conveyed by unbelievers. In his day, this was most obviously the pagan Greek philosophers. Many of his fellow Muslims held them in suspicion (a sentiment some shared in the Medieval Christian world), citing their denial of the Quran’s God. Yet Averroes insisted that truth overpowers narrowly interpreted dogma as a prevailing force that is proper to man as such. The Muslim would do well to remember this, he admonishes, since:

when a valid sacrifice is performed by the means of a tool, no consideration is given, with respect to the validity of the sacrifice, as to whether the tool belongs to someone who shares in our religion or not, so long as it fulfills the conditions for validity.

Submitting to the demands of truth, regardless of its source, resides deeply within Islamic tradition. While the faith has always had, and continues to have, those who restrict the Muslim mind, its history bears witness to the possibility of a more intellectually wholesome engagement with the world, a necessary prerequisite for negotiating the crises we face today. Averroes is only one of many examples of this.

This is markedly different from many of the loudest voices today on this issue, both from within Muslim communities and from the ‘woke’ brigades that claim to act as ‘protectors’ of the ‘oppressed.’ Within Islam itself, there is the danger of literalist interpretation—which has always lived alongside a more fully engaged Islam—and in the modern offshoot of Islamism, often classified as the bastard child of Islamic fundamentalism and Marxism.

The question of Islam’s role in the West and the wider world is too important to be left to scheming ideologues. There is no denial that this strange marriage between ‘woke’ warriors and Muslim fundamentalists is wreaking havoc. Needless to say, this is a very complex issue that lacks a clear solution. However, as with any conflict, truth must remain the shared object. As Averroes said, “truth does not oppose truth, rather it agrees with and bears witness to it.” Both Islam and Christianity, the West’s bedrock, contain within their traditions the mutual recognition of this central aim. To help overcome the challenges we currently and will continue to face, the spirit of inquiry, openness, and dialogue that animated the court of Al Ma’mun can be looked to as an authentic and worthy fellow of our traditions.