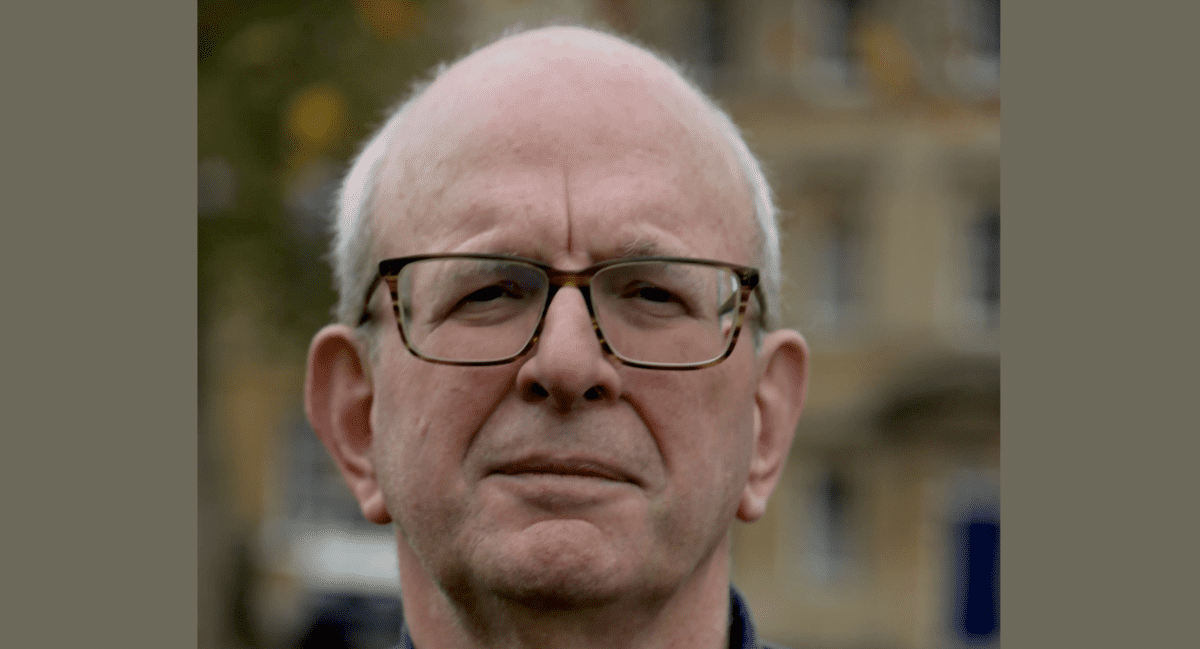

Edward Hadas is a Research Fellow at Blackfriars Hall, Oxford. He was previously an economics editor and columnist for Reuter’s Breakingviews. He also worked on the Financial Times’ influential “Lex” column, following 25 years as a financial analyst with firms such as Morgan Stanley and Putnam Investments. He has authored several books: Counsels of Imperfection, Money, Finance, Reality, Morality, and Human Goods, Economic Evils. He is currently working on a new book on Modernity, titled: The Moreness of Modernity: Four Narratives.

You wrote a book on the Social Doctrine of the Church called Counsels of Imperfection. In your opinion and experience, where can the Church influence society with its social teaching?

I think that the bishops, particularly in Western Europe and in the USA, are asking themselves the same question, as they should, and maybe even more intensely. In Africa, on the other hand, the question is less pertinent, since the Church is still well respected in society, working as a mediator in political and social disputes. In economic matters too, the Church there still has much to say and to contribute. In Europe on the other hand, the Church has, for the first time in about 1500 years, lost respect. Incidentally, Pope Francis addressed the Bishops of Europe just a couple of days ago and encouraged them to do things that a lobby group would do. He barely mentioned the importance of Christianity in society at all. He seems to hold that the bishops would be most successful as a lobby group for all things good in society, and that the Christian vocation is somewhat secondary. I am not sure that is the right answer. I think the Pope already takes for granted that the bishops have no voice. The then-Cardinal Ratzinger pointed out repeatedly that the Church’s place in society is to be a voice of conscience. It needs to be organized where it can and exemplify the Christian life. That will change society. Merely as a lobby group, the Church remains ineffective, so I do not think that is the way to go forward.

Charles Taylor claimed we live in a “secular age.” In your book, you have described the relation of modernity to its Christian past as a Freudian Oedipus Complex. In your view, does the future hold a reconciliation between child and parent, or will offspring live separated with an anti-Christian complex?

The great psychoanalyst Melanie Klein’s daughter was so rebellious against her mother that she initially refused to go to her mother’s funeral, and when she did go, she entered dancing ostentatiously and wearing a bright red dress. I am afraid modernity is more like Klein’s daughter in relation to the Church, than like the reconciliation we all wish for when our own children rebel. As time goes by, anger against the Church and the Christian tradition seems to grow stronger. This rebellion has been, in many ways, a path to ruin. Until the spirit of modernity perceives itself as being in a place of need, I fear this hostility towards underlying Christian values will continue. The natural effect is that the values are increasingly distorted. Modernity promises freedom, but in effect, it increases control; it promises more peace, but weapons and war abound; it promises equality, but fosters an ever more sinister elite that replaces the old one. Without rediscovery of the Christianity that lies at its core, the rebellious child is lost.

You are working on a book on Modernity. Why, what remains to say, and what do you hope to accomplish for the ‘modern’ reader?

The plot line is very simple: there are two stories of modernity, a cheerful one, which is told by the optimists, and a grim one, which I just alluded to. These two ‘versions’ of modernity are intertwined. While the world gets better in one way, it gets worse in another.

What can be accomplished by my book? Well, I am convinced that knowledge is always a good thing. I hope my explanations persuade people to see that taking a one-sided view of modernity, either extremely positive or extremely negative—which is usually what people do—is unhelpful because they are leaving out parts of the whole picture. What we really should do is re-integrate Christianity into the modern experience and try to get the best out of modernity instead of the worst. Unfortunately, this book suggests that history is not progressing towards compromise, but rather towards an ever sharpening distinction between good and bad. The modern world emphasizes this sharp contrast. In this way, it is worse than anything pre-modern. As a Christian, and in my personal life, I call on people to incorporate values that transcend this conflict, but as a cultural observer, I fear that there will be no improvement.

In the field of economics, you have been a prolific commentator. The IMF chief warns of global economic instability due to bank failures, monetary tightening, and the Russian-Ukrainian war. What is your take on the situation and your prognosis for the coming decade?

That is a good question to which I have no good answer. The future is unknowable. What we have seen in the last 100-200 years is very bad management of the financial system. We have, however, learned how to do better. The comments of the IMF are what they always are: something obvious, which you can read in the newspapers. It is also evident that something we are still not able to grasp is how to run both the monetary system and the financial system well. We are always on the cusp of spiraling out of control. I am not persuaded, however, that this is that moment. We were in trouble in 2008; that was fairly serious. But we recovered. And my guess is that we will recover from this as well. That said, I am quite cheerful about the economy. From a philosophical perspective, we can ask ourselves if the economy has brought us prosperity. I think we are doing pretty well on that front. We have comfortable, safe lives. Unless you think we need to grow the economy constantly, it is a great success, compared to anything we have seen before in terms of comfort, employment, and all human activity. Until a couple of years ago, we also saw rapid economic growth in most of the developed world, some of which is reflected in statistics and some of which is not.

I am not persuaded that the problem with the modern world is really the economy. We spent most of our cultural efforts improving it in the last century, and we can happily say it was not a waste of time. All that cultural and intellectual effort has made us richer, massively richer. The economy helps us to have things, make things, control the earth, and help the human condition. We have done all of that. From a Christian point of view, however, we should focus on where things have gone wrong in modernity. And for that question, I would not start with the economy.

You describe greed as one of the central malaises of the economic system. Can you elaborate and can you give a constructive proposal, if and how there is a possibility to minimize, or even eliminate greed? Are there incentives to do so for the economist?

We cannot eliminate greed. That would be like eliminating lust or pride. These are sins and we hope to be purified of them. But in this life, the stain of original sin remains with us. The question is how we fight it. From a societal point of view, the question is how do we arrange our communities, our laws, our customs, even our expectations to make it so that these sins are not encouraged, but discouraged. Do we put people in prison? Do we use shame? We generally use a combination of the two. I am not a utopian here, and this is important because economics has attracted utopian thinkers. That is very unhelpful. We will never achieve a perfect economy. I was just praising our economy, and that is not because I think it is perfect, but because I think it is as close to perfect (or imperfect) as it is likely to be, considering the fallen human condition from a narrow economic angle.

Greed, I argue, is actually under some sort of control, reasonably good control, in most of the economy. People do not admit to being greedy when they run corporations or consider new employment. They think of themselves as wanting a fair deal. They think of themselves as being appropriate and just in their dealings. When an outsider argues it’s greedy for the CEO of a company to get paid $3 million or $20 million, the executive will justify his pay by referring to a compensation committee that approves salary levels. We have some kind of arrangement that shows that this is a fair deal.

We think of greed as shameful in the economy—as it should be—because the economy requires us to work together for a kind of common good that we share and believe in.

When we think of the concept of greed, we often associate it with negative connotations. The idea of an individual or a company seeking excessive profits or gains at the expense of others is viewed as detrimental to the economy and society as a whole. In most cases, this view is accurate—greed can have a destructive impact on our communities and lead to exploitation. However, it’s important to note that there are instances where ambition, which can sometimes be viewed as a form of positive greed, proves to be beneficial. When you invest in the stock market, for example, or you buy bonds, or a piece of property, or an equity share, your primary goal is to earn a return on your investment—the idea is to make money without necessarily having to put in a lot of effort. This desire to maximize your profits without expending much energy is, at its core, a form of greed. This type of greed is not inherently harmful. In fact, it’s what drives the financial industry. The pursuit of profits is what motivates investors which in turn provides companies with the capital they need to grow and innovate. In finance, greed is not discouraged; you are not supposed to cover up for it.

Over the last 30-50 years, the constraints on financial greed and the social shame that it created have diminished. The sense of being a financial speculator used to be a bit disreputable. That has started to lessen, but we are far from discouraging greed. We seem to think that there is some kind of core value at the heart of the financial system. This seems to be one of the underlying problems. Credit Suisse just failed and was taken over by its Swiss rival. When you look at their balance sheets and their history over the last couple of years, it shows that they were completely fuelled by greed. Their raison d’etre was to encourage people from abroad to evade taxes and safely invest their money in Switzerland. Well, that is a kind of greed from both the Swiss bank’s side and the side of the investors. I’m happy to report that this doesn’t pay off in the long run.

Those of us who want sin to be punished in this world can look at finance and see that, at least some of the time, it is. It comes back to you in this life, and that’s how it should be. Greed should not pay off. However, all too often in finance, it does. But at least some of the time, at an institutional level, the most greedy institutions generally end up badly.

We should discourage greed. To do so requires a serious review of finance. I do not think this is impossible, in fact, I think it would be pretty straightforward. Yet, I am afraid we are not going to do it.

Perhaps your book will be a starting point for some to invoke change in the economic system. Thank you very much for your time!

Thank you for having me.