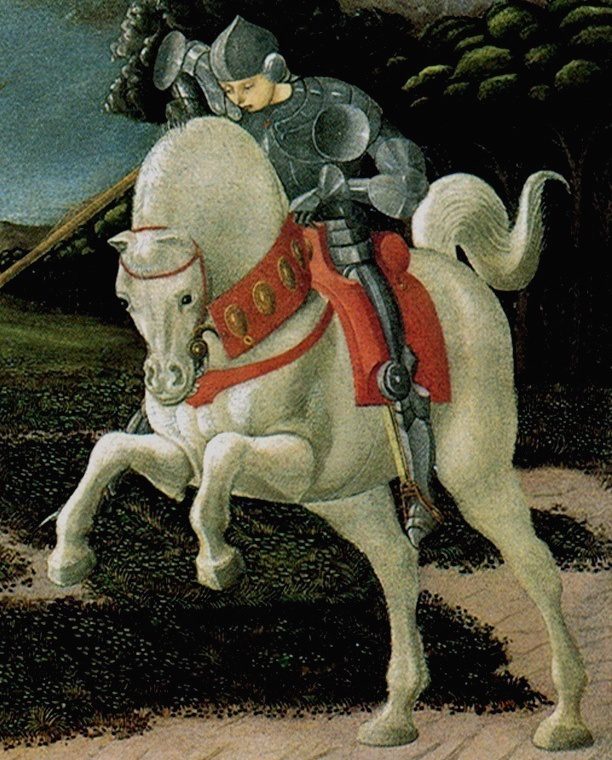

“Saint George and the Dragon” (ca. 1470), a 55.6 × 74.2 cm oil on canvas by Paolo Uccello (1397-1475), located in the National Gallery, London.

Besides the congealed bread and butter pudding (served every Tuesday) for which I maintained a peculiar liking, one of the few things that kept my spirits up during the era of discontent that was my boarding school years was a print I kept above my desk. The imitation of Paolo Uccello’s Saint George and the Dragon (1470) in the corner of my dormitory I would sometimes gaze at for hours, becoming transfixed by it until disturbed by some bored prefect looking for an underling to torment. The image holds a didactic power that worked on my mind throughout my teens and provided me with an image of a ‘great soul,’ the possession of which is an aspiration I think ought to haunt us throughout our lives.

To this day, Uccello’s depiction of St. George is burned into the grey matter somewhere at the back of my right hemispheric frontal lobe, I expect, and I return to it again and again in my imagination as both a friend and a teacher. When I am in London, near Trafalgar Square, I can’t resist visiting this image in the National Gallery. The magic contained in each brush stroke as well as its spell over me hasn’t faded with time.

When the name of Uccello comes up in conversation, people typically begin to talk about perspective. Yes, Uccello is indeed famed for his pioneering work in visual perspective. The polymath Giorgio Vasari, writing a generation after Uccello, described the great artist as being positively obsessed with perspective, describing his all-night vigils in his studio as he strived to grasp the exact vanishing point, in the hope of creating a sense of depth in his paintings which he deemed the mark of true artistic perfection.

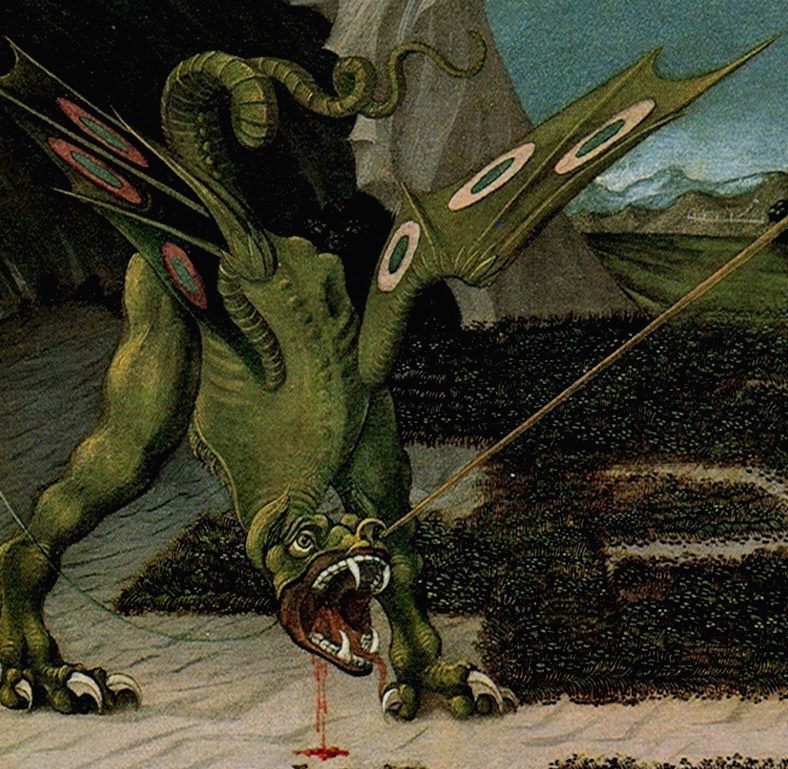

Certainly, a preoccupation with perspective and depth can be identified in Uccello’s George and the Dragon, with the stylised grass patches on the foreground having no other obvious purpose. And, unfortunately, Uccello doesn’t quite achieve what he’s aiming for: the patches of greenery recede towards the horizon while the stones on which the grassy slabs lie like cut turf slope up to the right of the picture. Be that as it may, where he does get it right—and you can look at the wings of the dragon to see how right he can get it—by his talent with perspective he injects astonishing movement and complexity into the image.

Besides his cleverness with perspective, Uccello is a master of presenting blazing action set within a certain calmness that prevents his paintings from becoming draining for the beholder (obvious examples of this are his famous three depictions of scenes from the Battle of San Romano). He depicted the encounter of George and the dragon twice before he attempted the one which is now universally admired, neither of which have the perspectival depth nor the dynamism of his eventual achievement in 1470—five years before he passed away, aged 78.

The technical virtuosity of Uccello, however, is not what primarily interests me. After all, this painting was clearly not produced in the service of some wealthy patron. Indeed, it’s a small painting (just 55.6 × 74.2 cm) on canvas with no expensive pigment or gilding. Many art historians think it may have been painted for a private home, perhaps for a personal friend. And such a possible history may help to explain the relaxed intimacy with which the painting is permeated (gorgeously expressed in the princess’s tranquil countenance). What interests me, far more than the technical skill of its author, is the message which conveyed itself to me in those lonely hours as a captive teenager.

First: the princess. She stands with neither fear nor anger, but utterly composed in the total trust she has in George’s promise. She has bound the dragon herself and led him from his lair into the trap. Initially, it looks as if the dragon is tied by a chord held in her right hand, delivering the creature to George’s wrath with her left. But on closer inspection one sees that with her right hand she is lifting her dress from under her feet, and the great serpent is in fact ensnared by the cincture around her waist.

Those familiar with Roman Catholic popular devotion may immediately think of the Blessed Virgin, whose perpetual enemy is the dragon. It is held that as she was assumed into the celestial court—where she has ruled ever since as Queen of the Universe—she dropped her cincture to St. Thomas the Apostle before he left to evangelise the Indians. Somehow, it made its way to Prato Cathedral, where it is still brought out a few times every year (I was there for one of those occasions about a decade ago, and I personally kissed the relic). I’m informed that there are other such ‘holy girdles’ around the world in other cathedrals, but I suppose it’s possible that she could have thrown down more than one on her departure. Let’s hope so.

In the Book of the Apocalypse, the dragon waits as a Woman crowned with twelve stars, with the moon under her feet, gives birth. He wants to devour her Child—and all her children (Apoc 12:1-3). There is always enmity between the Woman and the dragon, but the Woman does not fear the dragon. And indeed, Uccello gives us an image of this eternal enmity, as the princess, moved neither by fear nor despair, in an act of total trust leads the dragon out of the darkness and into the light where nothing can be hidden, offering him, as the Book puts it, to one “with a rod of iron” (Apoc 12:5). And it is with such a weapon that George comes racing out of the woods, smashing its point into the drake’s face.

In this painting, then, we have an image of the Virgin (who also embodies the mystery of the Church), we have an image of the Saviour, and we have an image of the devil. The painting turns out to be both a catechetical picture and a prayer that His will be done.

George comes dashing out of the wilderness. He is exhausted. His eyes are half closed with tiredness. He is hunched with fatigue over the neck of his charger. But he rides forth to fulfil his mission till the end. It is almost as if the sheer speed of his white steed has swirled the rainclouds behind him, and from the eye of the cloud descends his great lance, presenting the young knight as a conduit of divine action: “And behold, a white horse! He who sat upon it is called Faithful and True, and in righteousness he judges and makes war. His eyes are like a flame of fire” (Apoc 19:11-12).

The sheer muscular structure of George’s stallion is extraordinary. It is difficult to comprehend how Uccello conveys to the viewer in oily paint strokes the concentrated power of that enormous silvery beast. Jesus Christ tells his followers to be meek (Matt 11:29). It is easy for us to think of ‘meekness’ as an effeminate virtue, a mere inclination to keep one’s head down and try not to say too much. ‘Meekness,’ however, comes from the old Roman craft of horse-breaking. When a great stallion was utterly unrideable, out of control, and wild, but couldn’t be discarded due to its usefulness as a warhorse, the best horse-trainers were employed to ‘meek’ the animal. The task was to bring all that power and strength under the ordered will of one who could actualise the horse’s full potential, not by crushing or weakening it but by beautifully ordering it. When Christ tells his disciples to be meek, he is telling them to place all their strength and power at the service of the Gospel, that it may be used for the highest good. The courage of George combined with the inexorable force of his white charger as they form a single centaurial juggernaut of unstoppable power is a perfect portrayal of Christian meekness.

George appears in the night, unafraid of the darkness, guided only by the light of a thin, waxing crescent moon. He has soared through the forest to confront the embodiment of evil. George comes onto the scene as if having descended from above, whereas the dragon, who has “been thrown down to the earth,” slinks out of the world’s bowels, where he has reigned as chief mischief-maker and tormentor (Apoc 12:13).

Behind the writhing creature, in the shadows of his cave—which is seemingly formed of two huge, folded batwings rendered in stone—are rushing waters. Water is typically a symbol of life in both art and literature, and for obvious reasons. But water is also treacherous, and it threatens to suffocate life out of us: “The serpent poured water like a river out of his mouth after the woman, to sweep her away with the flood. But… the earth opened its mouth and swallowed the river which the dragon had poured from his mouth” (Apoc 12:15). Thus, the worm’s menacing waters slosh in the belly of the earth.

Undermining any realism is the painting’s lack of shadows. The shadow that is there, however, is symbolic, for the only shadow stems from the cave and stretches out under the dragon’s gut. Light is expelled by his presence, and since darkness is not a thing in itself but a mere absence of light, we see that the dragon’s evil is not creative, but only picks away at that which is made. The dragon, then, for all his monstrousness, is a pathetic being—this is what the shadow tells us.

George springs from the depth of the forest as the dragon lumbers forth from the earth’s belly. The forest, the woodlands, the heart of nature is where George has tested and found his mettle, for it is nature that must be redeemed and salvaged from the curses of the drake. No doubt on several occasions the princess sought to flee “from the serpent into the wilderness, to the place where she could be nourished,” as the Apocalypse puts it, “in the wilderness, where she has a place prepared by God” (Apoc 12:14, 6).

Creation is our friend, and it is creation that the dragon seeks to deface. George is at home in the woods, where he first heard the beckoning of the princess, and it is to that “place prepared by God” that they shall return together, when the enemy has been defeated. Beyond the wooded wild, at the centre of the scene is a distant city, indicating that the spiritual struggle embodied in the fight between man and serpent is for the sake of our civilisation—for the life of the polis—which will only ever be a meagre reflection of our true urban home in the life to come.

The dragon coils his tail behind him, seeking to suck the viewer into the circular narrative of the pagan mind, but the straight line of George’s lance points us to the linear account of our existential drama, asserting that we are a people possessed by meaning, with a purpose, and a home to which we are travelling.

The secret of the dragon’s face is of extreme importance. Why does George aim for the face of the dragon? Faces are deeply mysterious objects, for they are objects that disclose subjects. When I look at my friend’s face, I do not see skin clinging to a skull; I see a person, my friend, looking back at me. It is perfectly possible to look at my friend’s eyes without looking into his eyes. Faces are unique in this regard. Unlike any other part of the body, or anything else in the world, faces are objects that emanate subjects. As Roger Scruton observed: “There are deceiving faces, but not deceiving elbows or knees.”

The face of the dragon is the deceiving face par excellence. It discloses no person at all, and certainly not a person capable of seeing other persons. It is a face that doesn’t do the job of a face, for it doesn’t interface. What’s George do to when confronted by such an object, which is so obviously an offense against all that is natural and decent? George, precisely because he is meek, smashes that false face to pieces.

If you look at the dragon’s mouth, you can almost hear the horrendous shriek. All the noise of our modern world—all the bangs and screeches, the constant blare that purports to be music, the chomping of machinery and crackling of burnt rubber—all the bubbling, clamour, and racket of a technologized mayhem are captured in the blood-filled jaws of that wretched creature. And yet, looking at its open eye, one almost pities the dragon, as it’s the eyes that betrays its pathetic spirit.

What perhaps amazes me most about this painting is the ingenious admixture of movement and serenity. It is as if all the dynamism and excitement of the fight are seen in one eternal, timeless moment. In this way, Uccello coxes the viewer—just for an instant—into seeing the world as if from God’s perspective. And it is to adopt God’s perspective on things, to enter into His life and share His vision of existence, that He has revealed His inner life down the ages. For this reason, Uccello is a mystical teacher, and we should accept him as such.