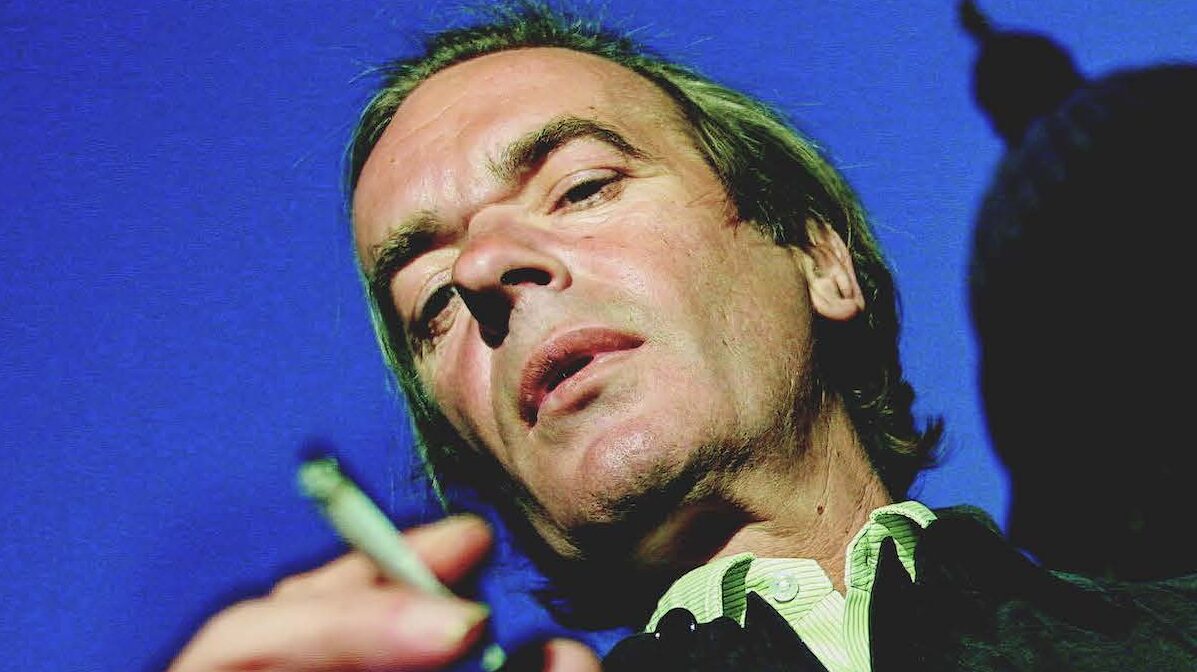

Martin Amis pictured at the Old Quad at the University of Edinburgh where he and Zadie Smith jointly won the James Tait Black Memorial Prize in 2000, the UK’s oldest literature award for their works.

Photo by Colin McPherson / Corbis via Getty Images.

Novelist, memoirist, and literary celebrity Martin Amis died at his Florida home on May 19, 2023. He succumbed to esophageal cancer 12 years after his best friend Christopher Hitchens, a fellow British expatriate, died of the same disease in a Texas hospital. He was 73. After half a century of era-defining writing, Amis leaves behind a memoir, two short-story collections, 15 novels, and seven books of journalism and history. Amis, Hitchens, and their literary set rose to fame as the sexual revolution dawned, and their lives and work were inextricably intertwined with the social upheavals that transformed the West.

There was a morbid symmetry to the lives of Amis and Hitchens—cancer, likely caused by their shared lifestyle, at the end, near misses at the start. Hitchens wrote that he was in his “early teens when my mother told me that a predecessor fetus and a successor fetus had been surgically removed, thus making me an older brother rather than a forgotten whoosh.” Martin’s father, Kingsley Amis, the legendary comic novelist, found an abortionist when his 19-year-old girlfriend Hilly became pregnant, but changed his mind out of concern that the “nasty man” might harm her. When she became pregnant with their fourth child, however, he forced her to abort Martin’s younger sibling.

Amis’ novels—like those of most of his contemporaries—are not my cup of tea. He was a genius prose stylist, but as with Phillip Roth and John Updike, the pornographic nature of many passages makes them unreadable for me. “What I’ve tried to do is create a high style to describe low things: the whole world of fast food, sex shows, nude mags,” he told The New York Times Book Review in 1985. “I’m often accused of concentrating on the pungent, rebarbative side of life in my books, but I feel I’m rather sentimental about it.” That’s the problem. Technical skill aside, his writing often seems like literary masturbation.

That is not to say that Amis was unwilling to tackle the ugly side of the sexual revolution, a subject he frequently examined in his journalism. In 2012, for example, he prophetically told Jacob Weisberg of Slate that pornography was going to “change human nature.” He was one of the first (male) liberals to identify the cultural impact that ubiquitous pornography would have on upcoming generations.

After a trip to a porn set, Amis professed his horror at what he found. He observed that the impact of the industry:

[It is] incalculable, and will change the nature of sexuality from here on. One suspects that any child old enough to walk will within a few months have access to it. I think it’s a great attack on innocence, and I know from personal conversations with my children that pornography determines the style of the whole operation. And since that form is … misogynistic, I can’t believe that’s a good thing. [Porn is] widening the chasm between sex and love. Pornography must set itself against significance in sex.

He was right about that. “I shudder to think what my girls have certainly seen,” Amis went on.

The effect of pornography on sexual praxis— how does it bleed into that, I’m sure it does, I know it does. My oldest daughter—I had many candid conversations with her when she was in her twenties, about how certain things were expected, just taken from pornography, which, lest we forget, is a very misogynistic form. Why does every sexual act end with something girls hate?

Amis got the collective cultural impact of pornography right while most were still defending it—and his views are now increasingly the consensus of researchers. “Porno, it seems, is a parody of love,” he wrote. “It therefore addresses itself to love’s opposites, which are hate and death.”

What Amis identified in his essay on the porn industry applies to the entire sexual revolution. In an era of boundless choice, violence and darkness once restrained by morality have been released. Market forces heed only our own carnal gods. Amis admits this with startling candor. “As I sampled some extreme productions on the VCR in my hotel room, I kept worrying about something,” he wrote. “I kept worrying that I’d like it. Porno services the ‘polymorphous perverse’: the near-infinite chaos of human desire. If you harbour perversity, then sooner or later porno will identify it.” Here again, Amis proved prophetic. Every human heart harbors perversity; pornography draws it out, nurtures it, and causes it to metastasize. Since the publication of that essay, pornography has successfully mainstreamed sadism in the sexual context—even among high school students.

Amis was clear-eyed about the fact that women paid the price for the ‘freedoms’ the sexual revolution released. His younger sister Sally, he wrote, was one of those women who desperately needed protection from men but, in an era of liberation, was left exposed and vulnerable as social mores collapsed around her. “She died at the age of 46, not of anything sudden; she was one of the most spectacular victims of the revolution,” Amis reflected. Sally’s daughter, conceived after a one-night stand, was given up for adoption. Her marriage ended after mere months. “She was pathologically promiscuous,” he said. “She really had the mental age of someone who was 12 or 13 and I think she was terrified. I think what she was doing was seeking protection from men, but it went the other way, she was often beaten up, abused, and she simply used herself up. … it’s astonishingly difficult to find a decent deal between men and women and we haven’t found it yet.” Even Hitchens slept with her.

Sally was the subject of his 2010 novel, The Pregnant Widow, which explored the fallout of the sexual revolution. He took the title from a phrase by the 19th-century Russian intellectual Alexander Herzen, who observed that revolution created “not an heir but a pregnant widow … [revolution] is a long night of chaos and desolation.” The old order is dead, but the new one has not yet been born. Amis agreed: “In other words, revolution isn’t a flip. It’s a churning process that goes on for a long time before the baby is born. It’s not the instant replacement of one order by another.” It is a metaphor that perfectly encapsulates our age. Amis lived long enough to see that the sexual revolution only benefited a few—handsome, talented, wealthy men like himself. The vulnerable, like his sister Sally, paid the price. And when the capitalist carpetbaggers of the revolution hijacked the minds of a generation with pornography, he correctly predicted that even sexual taste would be shaped by market forces.

We are still in that pregnant widow moment. The sexual revolution has irrevocably—perhaps irrecoverably—changed everything. Many, like Martin Amis, recognized and recognize that the freedoms we have gained may not have been worth the cost (Louise Perry’s magnificent 2022 tome, The Case Against the Sexual Revolution, was written, in large part, in defence of girls like Sally Amis). We know that the old order is gone; we know that what we are living through now is chaos. Amis defined himself as a writer exploring that chaos. However, we do not yet know what will come next—or the counter-revolutionary writers who may rise to define the new era when it arrives.

This tribute appears in the Summer 2023 edition of The European Conservative, Number 27:129-130