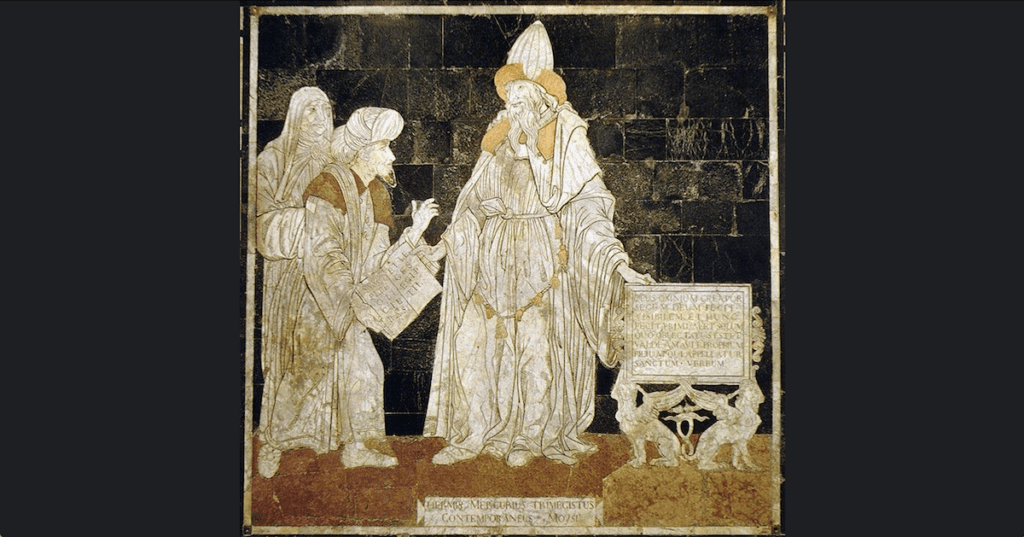

Hermes Trismegistus floor mosaic in the Cathedral of Siena.

Alexandre Lacassagne, the French forensic pathologist who published a book on tattoos in 1881, would have been astonished at, and puzzled by, the explosion of elaborate and professional tattoos in the general population in the last three decades.

The theologian Karl Rahner may have done more to undermine the integrity of Catholic orthodoxy at the higher levels of theological scholarship than any other member among the Nouvelle Théologie cognoscenti. Though it’s difficult to say who deserves that particular accolade, as the 20th century provided so much competition. Be that as it may, Rahner famously made a remark with which I have found myself in increasing agreement as time rolls on and the decay of the institutional Church is ever more evident: “The Christian of the future will be a mystic or will not exist at all.”

Now, whatever Rahner meant by this sentence I’d likely deem anathema. Taken in isolation, however, this proposition seems to point a way forward in an otherwise impossible situation. The situation to which I refer is what I’ve been calling for some time now the Church’s “post-authority epoch.” When I say this, I predominantly have in mind the Catholic Church (being, as I am, a Roman Catholic). The ugly internal power games, moral relativising, and neo-caesaropapism of Orthodox senior clerics, however, have hugely undermined the authority of their offices, and it’s not even worth remarking on the state of the Anglican Communion and the various Protestant sects. The fact is, all the baptised are in the same boat when it comes to the current crisis: the institution that the Incarnate Word established on earth to lead “all nations” to “all truth” has lost its authority (Mt 28:19, Jn 16:13).

Recently, I picked up my copy of Pope John Paul II’s Veritatis Splendor to refresh my memory with respect to his arguments for the reality of intrinsic evils. Whilst I hold that moral thinking requires serious engagement with intentions, conditions, and circumstances, I reject ‘situation ethics;’ morality per se clearly liquefies once you deny that some acts are forbidden regardless of circumstances. But I wanted to analyse the arguments advanced by John Paul II against situation ethics, and to my shock I found that he advances no arguments. He simply says that both Scripture and Church tradition hold that some acts are always and everywhere forbidden, and that this is his teaching as Vicar of Christ. That three decades ago it was still possible for a pope to make claims on the weight of his authority amazed me. This would be impossible today; the papal office simply doesn’t possess the existential authority for such confident assertions anymore.

Since the late 19th century, the faithful have been subjected to ever more regular, and ever longer, papal encyclicals and exhortations. Under the current Pontiff, these have taken the form of very long essays, mostly comprising observations and occasional hints at the revolutionary direction behind their authorship. It is almost as if the present Holy Father is begging to be taken seriously by the faithful for a moment, as he feigns speaking to them on an equal footing. This, though, is not at all how he actually governs the Church, bypassing canon law and settled theology as he pleases, and persecuting those members of the faithful who won’t, so to speak, get with the programme. This, of course, is exactly what belongs to the psychology of an abusive man: he oscillates from begging to be loved and listened to, to throwing his fists around. A central reason why abusive people behave in this way is because they have lost authority. They can no longer be believed or trusted, and so they resort to begging, sentimental gestures, and then violence.

The hierarchy of the Church has almost entirely lost authority in the eyes of the rest of the faithful. This isn’t a speculative deduction offered in some attempt to explain the phenomena. What I am describing is the situation as it is—a matter of fact. Among the vocal, active Catholics of the second half of the 20th century, there were broadly three factions: the progressives, the trads, and the post-conciliar neo-cons. That third category was dominant until the reign of Pope Francis, but since then has nearly totally disappeared. The champions of the “hermeneutic of continuity” have, generally speaking, fallen silent. It was too difficult to keep it up. Francis has demonstrated that the post-conciliar age is an age of ecclesiastical and theological rupture, and to argue that this isn’t the case has become impossible. The neo-cons tried to maintain their position for the first five years of Francis’s papacy, attempting to render orthodox every one of his bizarre allocutions, but in the end, it just became too tiring and too embarrassing.

Among vocal, active Catholics, there now remain two dominant groups: the progressives and the trads. Neither of these groups has much confidence in the authority of the Holy See or the curia. The progressives never believed that the law of the Church, the dogmas of the Faith, or the moral law had any claim on their intellect or conscience in any case, beyond what they individually chose to accept. The trads always believed they were bound by such things, but see now that something’s happened to the Church’s government that makes it no longer trustworthy, and thus they look sideways at anything coming out of Rome. The progressives are happy to affirm the Church’s authority at present, but only because it serves their ideology to do so; they were certainly more reluctant under John Paul II and Benedict XVI. What this means is that neither of the two dominant groups of vocal, active Catholics trusts the hierarchy’s authority merely on the grounds that it belongs to the government of a divine institution. Thus, the Church is, as a matter of fact, in a post-authority epoch.

Catholics who believe what Catholics have always believed, and wish to worship as Catholics have always worshipped, seemingly find themselves judged as heterodox in the contemporary Church supposedly born from the “new Pentecost” of the Second Vatican Council (1962-65). Remarkably, as devotional life corroded under the liturgical experiments following that Council, and the popular piety of the laity was belittled, Catholic dioceses responded to this spiritual asphyxia by increasingly reframing the Faith as a purely catechetical enterprise—with or without orthodox teaching. At the very moment, then, when the teaching authority of the hierarchy is precisely what’s being called into question, and at the very moment when the Holy Father can’t stop tampering with the Catechism of the Catholic Church (so that it now teaches what was condemned as heresy in previous ages), the hierarchy has emphasised its role as Teacher. Few, of course, are convinced. The problem, too, goes all the way down: Catholics are as suspicious of the teachings from their parish pulpits as they are towards the stuff coming out of Rome.

Meanwhile, the Church from its highest echelons to the local diocese has been riddled with petty clericalism, law-breaking, sexual abuse, and general moral and financial corruption. Anyone who follows Catholic journalism will be well-aware of the depth of the rot. The clergy, many of whom are practising homosexuals who cannot in good conscience preach the Faith, are largely managing ecclesiastical decline—and are often content to say as much. They know they’ve lost any defensible authority before their own flocks, and this has caused them immense frustration. Many a Catholic has had the experience of disagreeing on some minor point with a cleric and immediately finding himself confronted by an enraged, red-faced cartoon character, pointing and frothing at the mouth. As one priest—one of the few good ones—said to me, “it seems to be something they pick up at seminary.”

A few years ago, I challenged a bishop over what I judged to be his breaking of employment law and violation of Catholic social doctrine. A priest soon wrote to me, expressing his horror at my lack of “caution” in challenging the “Lord’s anointed.” Interestingly, this priest didn’t tell me that I was wrong, only that the bishop shouldn’t be challenged seemingly on no other grounds than that he was a bishop. To think it’s appropriate to use language suitable for an authority that has manifestly been lost indicates how delusional these clerics truly are. This attitude is typical of the servile—rather than filial—obedience that has taken over the Church’s hierarchy. Indeed, without such widespread servile obedience, the hierarchy would never have been able to perpetuate so many unspeakable evils for which it is now universally infamous. The reason, of course, that so many clerics behave in this bizarre way is precisely because clerical authority is gone, and they are trying to keep the illusion of its existence going for as long as possible.

That the Church’s ministers are managing decline and have capitulated to the post-Christian world at every step is an open secret. During the COVID pandemonium, the Church’s bishops closed the churches. The Bishops of England and Wales pre-emptively begged the government to authorise the closure of their churches before the government had even proposed such measures. Pope Francis decreed that taking an experimental drug of malign origin was an “act of love,” and in violation of Church teaching he threatened Vatican employees with loss of employment if they failed to undergo the procedure. The hierarchy effectively proclaimed that, at a time of widespread alarm and instability, the Church would not be there for the faithful. Worse still, it would help to foment the draconian measures, power-grabbing, and destruction of civil liberties by state governments. For the first time in the Church’s history, the Apostles’ successors apocalyptically cancelled the festive liturgies of the Easter Octave. The Church’s teachers in effect declared that sanctifying the faithful, preaching the Gospel, and making disciples of all nations, did not constitute ‘essential services.’ If the Church was not fully in the post-authority epoch before all that, it certainly was by the time we were coming out of the lockdown tyranny. And many of the faithful, quite understandably, have never come back to Mass.

Tolkienians will understand the overriding mentality of the clergy. I call it Denethor-mentality, after the Steward of Gondor in The Lord of the Rings. A man desperately holding onto power, whose behaviour and form of government is becoming increasingly erratic and self-serving, who cannot see what is required amid a crisis, who concedes evermore territory to the powers that want to destroy his realm, who rejects that on which his authority rests, and who rewards foolishness whilst seeking every opportunity to crush his only remaining, faithful and devoted son. That is Denethor-mentality, and it is the dominant mentality of the Catholic clergy.

Since the late medieval period, every form of check and balance in the Church has incrementally diminished. The influence of the temporal power of the Church, namely the laity, on ecclesiastical matters has so ebbed that the laity now has no influence whatever. The clerical hierarchy—especially the pope—is now totally unchecked. If the pope has an idea, he can type it up on a piece of paper, put his name at the bottom of it, and suddenly that becomes law. And that is exactly how Pope Francis governs the Church. The situation is ridiculous and, again, has corroded to the point of destroying the last residue of authority in the Church.

In the so-called age of ecclesiastical collegiality, there is zero collegiality. The whole thing is a smoke-screening exercise. Attempting to make sense of this situation, the faithful have increasingly fallen back on the sensus fidelium to ‘tap into,’ so to speak, the true faith of the ages that is being covered up with recurrent acts of clerical voluntarism. The Church’s government knows that this is what is happening, and thus is diabolically seeking to imitate the sensus fidelium through the ‘synodal process,’ so that it appears that the ‘sense of the faithful’ conveniently affirms the revolutionary direction of the governing clergy.

Over the last century, the Church has undergone the greatest apostasy in its history. And yet, amazingly, people are still sporadically converting to Catholicism. In the West, such people—especially young people—are coming to the Catholic Church through the traditional liturgy and the wider trad movement. Indeed, a strange characteristic of the post-authority epoch is that the parish and the diocese isn’t really where Catholicism happens. Catholicism has largely become an internet genre. And whilst the Church’s government is doing all it can, from the very top, to destroy the trad movement, it certainly remains alive and well online. It is mainly by this virtual world that young people come to Catholicism in their attempt to escape the Manichaeism and nihilism of late modernity (which mainstream Catholicism only appears to offer in ceremonial form). On arrival into the fold, however, such young people soon find that their new spiritual fathers wish they’d never become Catholics. Having escaped the world that tried to ruin their souls, they find themselves in a Church that officially wishes they’d never existed.

The Church’s greatest modern theologians have been committed to explaining to us that nature is in fact supernature (à la Teilhard de Chardin), the difference between a Christian and a non-Christian is one of degree rather than of kind (à la Karl Rahner), and that everyone is going to be saved from damnation in any case (à la Hans Urs von Balthasar). Then Dignitatis Humanae—Vatican II’s Declaration on Religious Freedom—came along and seemingly cancelled the Church’s mission to the temporal world. By the end of modern theology’s process of conflating the natural and supernatural, dissolving them into one another in a perverse act of theological alchemy, Catholics were left asking: what is the point?

It’s not as if being a committed Christian doesn’t entail some serious challenges in a world that is increasingly hostile to such a life. If it turns out that certain sins cannot in fact be resisted, and therefore giving into them cannot be blamed on you, as Pope Francis has implied; that there’s no real difference between being baptised and being unbaptised; that venerating saints and worshipping Amazonian fertility gods is really all the same; that the Church isn’t actually charged with making disciples of all nations because religious pluralism is willed by God; and that everyone is going to be saved anyway, Catholics may reasonably feel that it’s preferable to throw in the towel altogether—and so they have.

The concordat with the post-Christian world, which is the overarching theme of the post-conciliar settlement, also implies that there’s no lay apostolate. Traditionally, the role of the clergy was to sanctify the laity, that the laity may sanctify the world, capturing it from the “prince of this world” and placing it under the Kingship of Christ. Were this apostolate of the laity to continue, however, it would seriously undermine the Church’s new concordat with the unconverted world, implying that there was some substantial difference between a sacralised world and a profane one, which would somewhat undo the nature-supernature conflation on which the Vatican II theology of ‘opening up to the world’ was indeed based. So, what is the laity to do in the modern Church? Carry the cruets up to the altar and join the parish folk band, I suppose. The laity may be forgiven for saying, thanks but no thanks.

I have barely touched upon the crisis. I’ve mentioned just some of the problems faced by the Church in its post-authority epoch. To cover the many manifestations of these problems and the many challenges that the Church faces would require an enormous tome (which I may write someday). For now, however, I only want to draw the attention of my readers to the fact that there is a crisis, and that crisis has moved the Church into a new mode of existence: the Church’s government has lost its authority, and the faithful should not only expect an intensification of mistreatment by arbitrary power from the hierarchy, as the hierarchy fails to come to terms with this reality, but the faithful will also need to work out what it practically means to be a faithful Christian in this new epoch.

Many today, looking around at the spiritual wasteland that is the West, seek to satiate their deepest religious thirsts by turning to romantic ideas of pre-Christian paganism, nature-worship, and New Age spirituality. Otherwise, they look east to the mysticisms of Asia, especially those of Buddhism and Hinduism, both of which have the added advantage of easily accommodating the individualism, solipsism, and anthropological dualism which have colonised the Western mind since the so-called Enlightenment. I threw myself into all these spiritualities, in fact—a sequence that culminated in my conversion to Catholic Christianity on the south coast of India in my late teens, and I’m certain that God drew me out of the West that I might encounter His Church beyond its visibly corrupt and decadent occidental condition.

In Crossing the Threshold of Hope, John Paul II speculated that many Westerners had turned especially to Buddhism because the practices of Carmelite spirituality hadn’t been properly disseminated among the faithful. Had they been taught such practices, he suggested, people would have seen that whatever they were looking for in eastern mysticism was already present in the Christian spiritual tradition. Now, I’ve read John of the Cross, Teresa of Avila, Brother Roger of the Resurrection, and Edith Stein. Carmelite spirituality, which I deeply admire, is a very monastic spirituality, and it’s difficult to see how it is applicable to life in the world. Admittedly, this gap was somewhat bridged by Therese of Lisieux’s autobiography, which hugely influenced lay spirituality. Nonetheless, it doesn’t seem sufficient to tell religiously hungry Westerners that they need not become disciples of Sri Sri Ravi Shankar, as they can just read John of the Cross and thereby create an oasis in the spiritual desert produced by Fr. O’Murphy’s weekly sermons on climate change.

We must spiritually engage with the situation at hand. As the West continues to plummet into its now unavoidable civilisational collapse, we shall see the rise of all kinds of superstitions and witchcrafts, which will likely serve to bestow a religious character upon the technocratic age of bio-government and transhumanism that we’ve now entered. The Church’s hierarchy has not only shown every sign of celebrating this diabolic trajectory, which it doesn’t even begin to understand, but even if it became critical of it, it remains completely unequipped to engage with the new global regime in the prophetic way that’s desperately needed. Those who see that we’re in for something quite different to the interminable capital-P ‘Progress’ that liberalism promised to deliver, are increasingly looking for a spiritual awakening that will reconcile us to God and to His creation that we’ve defaced, and the Church stands at the side-lines looking baffled at such people.

The West is entrenched in what the philosopher and psychologist John Vervaeke has called a “meaning-crisis”; whilst the institutional Church has entered an authority-crisis. I submit that the Church’s reclaiming of its mission is the only way out of the meaning-crisis of the West—a crisis that the West has successfully exported to almost every part of the globe—and at present the Church remains utterly unfit to take up this mission. Restoring any kind of credibility will not be the work of decades, but of centuries. By then, it may be too late. So, in the meantime, I suggest that the Church has before it the imperative to rediscover its role not primarily as an authority that makes truth-claims by which to bind the intellect and the conscience of its members, but its role as the path—“the Way,” as the early Christians called their religion—to encounter the God who is Love, through the mediation of Christ’s sacred humanity, in a profound and transformative mystical life.

In the current situation, it seems that the remaining Church’s faithful will persevere by opting to double-down on the devotional life. This is exactly what all the committed Christians I know are doing. They’re taking stock of the collapse of our civilization and the utter sterility of the institutional Church in the face of it, and in response they’re deepening their spiritual lives and clinging to Christ. The reason for which the Church exists is union of its members with the Triune God. And when the hierarchy’s members forget this in their pursuit of worldly ambitions, God’s people must consider what lies within their own spiritual repertoire and mine those resources to cultivate as far as possible the richest interpersonal relationship with Jesus Christ that they can; or better, that He can cultivate in them.

It seems to me that the paradigm of rationalism—with all its chaotic relationships, ugly architecture, shallow sentimentalism, fetishization of abstractions, legal positivism, and blindness to persons—to which the institutional Church has conceded so much moral territory, must be overcome if we are to recover the primacy of the mystical in the life of the Church. The challenge before us, then, is that of recapturing the theocentrism on which our civilisation was built. The Gospel, which the Church is meant to proclaim, is the means by which to do that, and the sacraments possess the power to effect the transformation that’s needed. Breaking out of the prevailing rationalist paradigm, however, is the fundamental precondition for recovering the theocentric paradigm that is its antithesis. And such a deliverance may mean that we’ll have to be more open to a broader Western spiritual tradition which has always been bound up with mainstream Christian spirituality, but which cannot be accommodated by the rationalist paradigm and thus has been eclipsed in recent times.

What I’m pointing to is the imperative to re-enchant our world, and in turn encounter the God whose emanated likeness it is. The onset of civilizational disenchantment was already being flagged at the end of the 18th century by the man of letters Friedrich Schiller, whose insights on this theme were taken up a century later by the sociologist Max Weber as he analysed the bureaucratisation of society in the modern age and its corollary, the reduction of atomised individuals to—as he put it—“cogs in a machine.” The pressing imperative to re-enchant our world, then, has long been acknowledged. I want to suggest that it may require a courageous recovery of the mystical, supra-natural, Neoplatonic vision that comprised the fundamental superstructure on which the Patristic, Medieval, and Renaissance projects were built—but which has been so alien to us since the dawn of modernity.

There is clearly enormous appetite for such an enchanted vision, as demonstrated not only by the turn of Westerners to the mysticisms of the East, but by the return of theories concerning a ‘world-soul’ and ‘living nature’ throughout the Western academy in the form of the latest scholarly superstition: physicalist pan-psychism. These are all feeble attempts to respond to the fundamental challenge that the West faces, and the Church is the only institution that possesses the supernatural power to respond properly. But to respond thus, the Church, in the titanic task of unshackling itself from the modern paradigm, may have to offer a chair at its table to Hermes Trismegistus, perhaps next to Plato, Aristotle, Cicero, Seneca, and so many other greats whom it has retrospectively baptised. How the Church might begin to do this will be the focus of Part II.