Viktor Marsai is the executive director of the Migration Research Institute in Budapest and an associate professor at the University of Public Service. He talked to The European Conservative about the causes of recent military takeovers in Western Africa, their effects on the region, and the wider implications of a deteriorating security situation.

Absolutely. We can even call it a wave of coups. The events in Mali and Guinea inspired the events in Burkina Faso. The Nigeriens are now mimicking the others: the generals leading the coup have a strong anti-French sentiment, they position themselves against the regional union, the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS), and we have also seen Russian flags being waved. According to news sources, the military junta asked the Russian mercenary group, Wagner, for help. It is no wonder that ECOWAS and other international actors issued harsh statements denouncing the coup. It remains to be seen whether actions speak louder than words. What we have seen in the region in the last three years is a reversal of democratisation. It’s hard to tell which country will be next. Let’s not forget that an attempted coup d’état failed in Guinea-Bissau last year. What we can say with certainty is that the security situation in these countries has worsened after the coups.

The Islamist groups have clearly strengthened, but I would like to point out that the coup d’état in Guinea had nothing to do with jihadists, as they are not present in the country. With regards to Mali, however, Assimi Goïta’s power grab was partly due to the deteriorating security situation the country had spiralled into, but ethnic conflicts also played a part, which the jihadists took advantage of. Security forces in Mali lacked power, so ordinary citizens armed themselves, and the jihadists then backed certain groups. These events then spread to Burkina Faso.

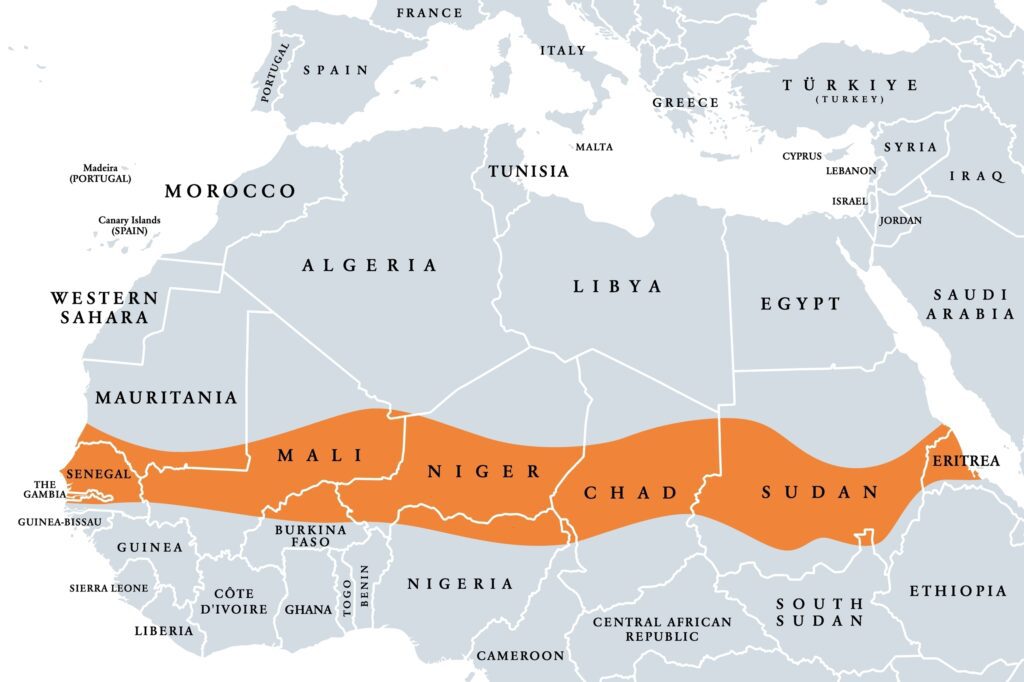

As for Niger, the opposite is true. So far this year, around 6,000 people have been killed in clashes in the Sahel region, 3,000 of those in Burkina Faso and 1,000 in Mali. However, only 70 in Niger, which is a 50% drop compared to last year. So the security situation was, in fact, starting to improve in Niger. And although Niger is one of the poorest countries in the world, the previous governments put the country on the right track economically. The coup d’état in Niger is nothing more than the changing of the guard among the country’s elite.

Only partly. This type of reasoning chimes with the disinformation that Russia has been spreading in the region in the past few years. If France hadn’t intervened militarily in Mali in 2013, the Islamic State might not have tried to seize territories in the Middle East, but instead focused on the Sahel. The jihadists would have swept the government of Mali aside and set up their headquarters in Bamako, the capital of Mali. However, the French were quick to react after the ethnic conflicts broke out.

They had no alternative but to back certain groups in Mali in order to maintain stability in the country: Without negotiating with certain Tuareg groups—who control the North and don’t have a good relationship with Bamako—it would not have been possible to stabilise the region. And it was an unrealistic scenario that France would send 20,000 troops to stabilise the whole country. The Mali government was part of the problem as well, because the black population of the south had no interest in defending the Arabs and Tuaregs of the north. Only when their own power was under threat did they start to care.

With regards to Niger, it is hard to accuse Western nations of acting like colonialists when a country is so dependent on their support. Niger received $1.8 billion in support from the West last year, while its GDP is about $16-17 billion, and currently almost 50% of the government budget is covered by Western sources. So the West is currently supporting the livelihood of four million people in Niger. I doubt that Russia and China would do the same without asking for something in return. Having said that, there’s no denying that the uranium and gold mines, as well as agricultural resources, are all extremely important for the French. Not to mention that the French don’t want the population of Sahel to head for Europe, nor do they want to allow terrorists to sweep through the region.

The latter theory appears to be closer to the truth. Russia doesn’t have the economic potential to be a rival to other global players in the region, nor did it have that potential before the start of the Ukraine war. Russian arms export is the only significant type of trade we can talk about as Russia is not in the top ten of the biggest outside economic actors in Africa. However, the Russians have realised how simple it is to cause big problems in Africa in a cost-effective way with the help of the Wagner Group. These problems have the potential of affecting Europe. One classic example is Libya, where the Russians are intent on having a drawn-out civil war, stopping Libya’s unification, and leaving the door open to irregular migration towards Europe. Current trends show that the growing number of migrants arriving in Italy are mainly coming from eastern Libya, whereas previously it was from the western part. Eastern Libya is under the control of the Wagner Group and its allies.

The second example is Sudan, where the Wagner Group has tried to delay the transition of power since 2019. This is also visible in Mali, where the arrival of the Russians has deteriorated the security situation, and many serious human rights violations have occurred, such as the massacring of entire villages. According to the Africa Center for Strategic Studies in Washington, the jihadists have been much more active since the arrival of the Russians. First the French left the country, then the UN peacekeepers–almost 17,000 soldiers overall. The 1,000-strong Wagner force cannot and does not want to fill that gap. Their troops are mainly stationed near gold mines, which says a lot about their aims in the country.

The Sahel region isn’t as important to France as it was ten or 15 years ago. France didn’t put up much of a fight when Mali ordered its troops to leave. The same can be said of Burkina Faso. Part of the reasoning behind the French decision is the cost involved. I would also like to point out that the harshest critics of the Wagner Group are not the Western countries, but the member states of ECOWAS. It says a lot about the situation that after the coup d’état in Burkina Faso, the new leader, Ibrahim Traoré, did not call on the Wagner Group for help after realising that the group is now responsible for the safety of the president in the Central African Republic and Mali. Anyone who is interested in the history of Ancient Rome knows that the Praetorian Guard didn’t always keep the emperor safe.

Coming back to Niger, the country is definitely important in terms of uranium, but France only gets 20% of its uranium supply from Niger. A sudden halt in trade would not endanger the normal functioning of French nuclear reactors. The rise of terrorism and irregular migration, however, could negatively impact European interests in Africa and Europe itself. This region is one of the busiest migration routes to Europe. The EU struck a deal with Niger back in 2016, which resulted in the country reenforcing its borders and the yearly number of crossings through Niger falling from 300,000 to 100,000. If the crisis is prolonged and the deal falls apart, these numbers could rise again. There are currently 3-3.5 million internally displaced people and refugees in the borderlands of Mali, Niger, and Burkina Faso. If the situation deteriorates quickly, hundreds of thousands of people could leave for Europe.

There is heated competition in Africa, and China is definitely one of the competitors. China is not doing badly in this area, but they are not doing that well either. China would like to change the international order dominated by and set up by the West after the Second World War, and China seizes every opportunity in places where it sees the West retreating. If we take the example of Niger, the big question is whether the wave of coups spreads through other parts of Africa or whether Europe makes it clear that this region is in its sphere of influence.