On Thursday, October 26th, the European Central Bank decided to keep its three monetary policy rates unchanged:

The interest rate on the main refinancing operations and the interest rates on the marginal lending facility and the deposit facility will remain unchanged at 4.50%, 4.75% and 4.00% respectively.

This was expected. A further increase in interest rates at this point, though necessary to fight inflation, would have been politically difficult for the ECB to motivate. It cannot stand alone as the sole economic policymaking authority to try to fight the recession that Europe is now going into.

Over the past few weeks, I have issued multiple warnings about this recession:

- Three weeks ago I raised the red flag and called upon Europe’s political leaders “to stop the slide into a new recession;”

- Two weeks ago I pointed to the risk that those political leaders, instead of improving business conditions and cutting taxes, would actually make it even more expensive to do business in Europe;

- Last week I reinforced my warning by pointing to the risk of an inflation comeback in the midst of a recession.

The decision by the ECB not to raise interest rates is designed to provide a little bit of help to the economy, primarily for credit markets. A new report from the ECB explains that banks in Europe are now operating as if they already were in a recession. Under the title “Euro area bank lending survey,” the report explains:

credit standards for loans or credit lines to enterprises tightened further in the third quarter of 2023. The cumulative tightening since 2022 has been substantial, which is consistent with the ongoing significant weakening in lending dynamics.

The banks also expect tighter conditions “for consumer credit and other loans to households.”

In no uncertain terms, this means that banks are getting worried about the solvency of their customers and want to reduce their exposure to higher-risk lending as quickly as possible. But it is actually worse than that: when banks tighten the terms of credit, they have in all likelihood already seen a rise in loan defaults.

That increase is symptomatic of a macroeconomic downturn, i.e., the opening phase of a recession. Naturally, it is prudent of the banks to react now, before a trickle of loan defaults turns into a flood. At the same time, there is a grim downside to this credit tightening, and it is this downside that the ECB is trying to moderate by keeping its interest rates unchanged.

Let us return to that part of the story in a moment. First, let me reiterate the big news in the ECB report on credit policies: the banks are tightening their conditions for new credit at the same time as demand for credit is falling. This means that both sides of the credit market are pulling back.

We saw this happen in the run-up to the Great Recession of 2008-2009. Back then, the falling demand for credit led to the downturn in the financial markets—a point not often made in analyses and commentaries on that event. (I covered it in my book The Rise of Big Government.) Judging from the ECB report, we seem to have the same trend in the market now: credit demand has been falling since early this year, while banks generally began tightening lending conditions only in the last few months.

The goal for the banks is, of course, to reduce their overall exposure to credit default risk. In a manner of speaking, European banks have now gone from playing offense to playing defense. It remains to be seen how strongly this move will affect the economy of the EU, but as a general point, this type of move by the banks can have a destabilizing effect on an already unfolding recession.

This is the grim downside of credit tightening mentioned earlier. It goes to work through the interaction of the credit market and the macroeconomic system as a whole. An important component in this interaction is the credit tightening that the banks are now doing. While it reduces the default risk of new loans, the tightening has no real effect on the existing stock of loans. This means that there is a relatively high risk that the banks did not act fast enough to stave off credit defaults; the pace of the improvement in the risk profile of their portfolio may be too slow to keep the weighted average risk acceptably low.

At this point, banks would love for customers with a lot of money and no credit risk to storm the banks. This, of course, does not happen; if anything, financially prudent bank customers reduce their borrowing when they sense a recession is coming. As the ECB report explains, this is exactly what Europe’s businesses and households are doing. The report spells out that credit demand among businesses “continued to decrease substantially in the third quarter of 2023.” This decline was faster than what banks had expected, as was the decline in demand for household mortgages, a.k.a., housing loans.

The absurd situation for the banks is that the one thing they need the most—lower exposure to credit default risk—is the least likely thing to happen. This, in turn, motivates them to double down on their credit-restrictive measures, which only narrows down the definition of an acceptably low-risk loan. Consequently, even fewer of those will be sold.

Provided, of course, that households are interested in borrowing. At the moment, Europe’s families and businesses seem to be going in the opposite direction: reducing their debt.

Let us be clear about the banks’ rationality here: they are doing exactly what they need to be doing in order to defend their solvency. This is not a problem they can solve. The root cause of their situation is macroeconomic; the fact that their response to the situation can contribute to further destabilizing the economy is not something the banks can, or should, take responsibility for.

If the measures taken by the banks go far enough, the destabilizing consequences of those measures can escalate to the macroeconomic level. There are no signs at all of that happening in this recession, but once banks start playing balance sheet defense, their fate—and the fate of the economy as a whole—is in the hands of the macroeconomic system, and those who make fiscal and monetary policy.

This is where the ECB’s latest interest-rate decision becomes relevant. It is aimed at stopping the erosion of banks’ credit sales to good customers, but also at easing the burden on existing loans with variable interest rates.

Interestingly, if we go back to the ECB’s own report on the commercial banks, it is actually implicating itself in putting the banks in their current situation. Demand for credit depends in good part, but far from only, on the interest-rate level in the economy. The ECB report suggests a clear causality here, from its own policies to raise interest rates to a decline in credit demand. However, that causality is far from clear-cut. The ECB report states that

Euro area banks’ access to funding deteriorated in all market segments in the third quarter of 2023, especially for access [to retail] funding. The pronounced deterioration in access to short-term retail funding … is consistent with the higher competition for liquidity stemming from other banks and from alternative investment opportunities offering higher remuneration.

However, the rise in interest rates that this report points to, is not a new phenomenon for the third quarter of this year. The yields on euro-denominated treasury securities have been trending upward since January. Figure 1 exemplifies with the 1-year, the 10-year, and the 30-year euro-denominated treasury securities:

Figure 1

The interest on government debt affects the cost of credit to households and businesses through a few simple steps. When banks want to supply loans to households and businesses, they borrow money on the open market, where they compete with—you guessed it—government. Since government also borrows money, and since government debt is generally considered to be a risk-free investment, banks have to compensate for the fact that they are not risk-free. They have to pay a higher-than-government interest rate.

Once the banks have borrowed the money, they turn around, add a markup to the interest they pay, and sell credit to households and businesses.

The ECB report suggests that when interest rates on treasury securities increase, as in Figure 1, it quickly becomes difficult for banks to sell their loans. The reason is that those who otherwise would lend their money to the bank choose instead to buy treasury securities. The banks, in turn, cannot compete because they cannot raise their interest rates high enough.

Government competition does indeed draw money away from commercial banks, but the reason why it is happening is not solely, or even primarily, dependent on rising rates. All other things equal, there will always be investors who want to invest across the entire risk spectrum. The problem for Europe’s banks today is instead that, in addition to rising interest rates, the economy as a whole is weakening.

All things are no longer equal.

The big story in Figure 1 is not that interest rates are rising, as the ECB report suggests, but that the relatively steady rise for most of this year is coming to an end. Yields on the treasury securities in Figure 1 have not risen as steadily in the last three months as they did earlier in the year. This is compelling: it means that more investment funds are moving into government debt—just as the ECB report said—but doing so because investors see something in the economy that they did not see six or nine months ago: a recession.

Again: the inescapable variable here is a recession that neither banks, nor households, nor business managers can do much about. The actions that the banks have now taken, while perfectly rational from their viewpoint, can now add a grain of instability to an economy that is already in a dicey situation.

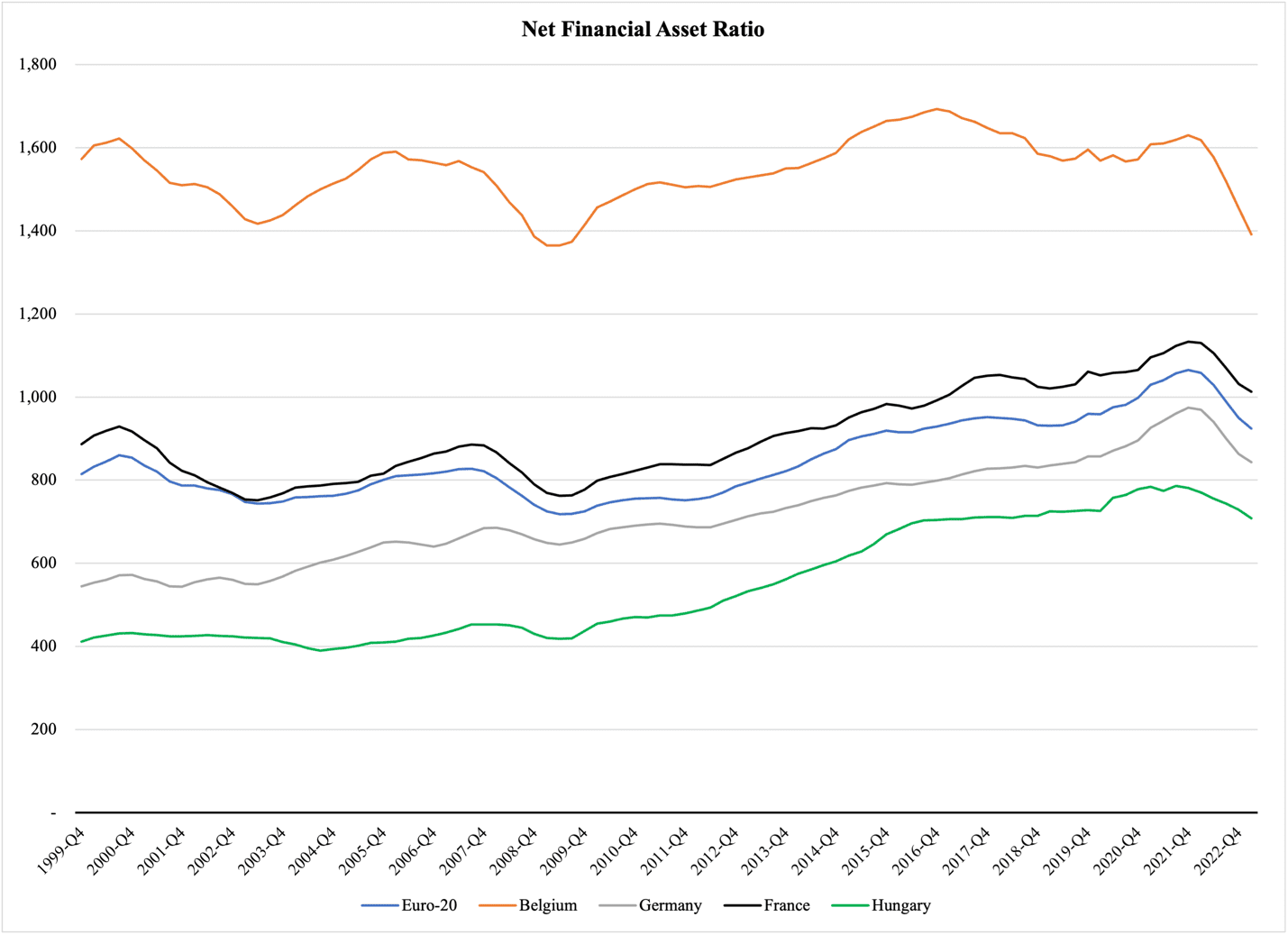

But wait—there’s more. Households across Europe have yet another reason to refrain from more borrowing. Figure 2 shows the net financial asset ratio for households in the euro zone as a whole, plus four select countries (chosen to give a diverse set of examples without clogging up the figure with too much information). The ratio, defined as the value of their assets less their debt, divided by their pre-tax income, is reported as a four-quarter moving average (in order to eliminate significant seasonal swings). A long, steady rise in the asset ratio throughout the 2010s is followed by a sharp downturn in 2022 and through the first quarter of 2023:

Figure 2

Households in the euro zone as a whole were worse off in the first quarter of 2023, with a net financial-asset ratio that was 1.7% lower than in the first quarter of 2019. The ratio fell over the same period of time in six countries, with an average decline of 11.1%; the average increase in the remaining 16 countries for which Eurostat reports asset ratio data was almost exactly half as strong: 6.1%.

It is too early to tell if households in general are worrying about asset values to the extent that it has affected their demand for credit, but it certainly cannot be ruled out. If asset values really are on the decline, as Figure 2 hints, then the collateral for much of the credit that banks would sell is weakened or goes away entirely.

Hopefully, the asset-ratio decline is just a readjustment of the ratio trend back to its long-term ‘normal.’ That would contribute to the containment of the recession and reduce the risk financial instability. However, even if this is the case, there is a psychological effect from a simultaneity of bad news for households: a recession combined with persistent inflation, higher interest rates, and weaker asset values, is a bad psychological recipe for the European economy.