There has been a lot of news recently about The Czech Republic joining the euro zone. On October 31st, Bloomberg declared that the euro is “creeping” into the country. With public opinion and government opposed to the common currency, corporate leaders “are increasingly taking the matter into their own hands.” They are “gradually nudging the economy” in the direction of euro membership.

Citing statistics from the Czech National Bank, Bloomberg explains that

for the first time half of all outstanding corporate loans from local banks in the country are denominated in foreign currencies—overwhelmingly euros—and the number is even higher if credit from foreign banks is included.

A couple of days after the Bloomberg article, Reuters reported on the political opposition to the euro:

The next Czech government will not adopt the euro, the man tipped to be the finance minister in the new centre-right coalition said on Tuesday.

They do not see the euro as a top issue for the next four years.

While Czech opposition to the euro is not exactly new, the government has had an accession plan in place since the Czech Republic joined the EU in 2004. As Bloomberg reports, there is growing private-sector pressure on the country to give up its own currency, but as the Czech National Bank concluded in last year’s euro accession assessment:

the Ministry of Finance and the Czech National Bank recommend that the Czech government should not set a target date for euro area entry for the time being.

With influential euro proponents determined to try to sway public opinion, the debate about the future of the Czech koruna is likely to continue.

In the midst of this debate, one aspect appears to be missing: the answer to whether or not the Czech economy would benefit from the currency transition. So far, attempts at answering this question are few and far between. The common approach to the economic dimension of euro accession is the one that the Czech National Bank takes in the quoted report above, namely to assess whether or not a country is in compliance with the accession criteria.

The accession criteria are important, but only temporarily: their purpose is to guide the transition process from one currency to another. The closer a country is to meeting the criteria, the more smoothly it will step from its own currency into the euro. However, these criteria say nothing about whether or not the euro will benefit a country aspiring for currency union membership.

An analysis of the economic benefits of euro membership must take a broad macroeconomic approach and shine its light on a multi-year stretch of economic activity. In other words, the real question regarding euro zone membership has to do with GDP growth, structural economic strength, long-term trends in public finance, and whether or not the labor market will do well under the euro.

While it is easy to make the case that a country meets the euro zone convergence criteria, it is far more difficult to find support for the euro in a comprehensive macroeconomic analysis. As I explained in my recent analysis of the German economy, for the past 20 years, the euro zone’s GDP has actually trailed behind that of non-euro EU states.

This little statistical factoid could be taken as an indication that the euro has hamstrung its members compared to non-euro economies. However, a more productive approach is to look at where the Czech economy is today in terms of macroeconomic essentials and see what difference a euro zone membership would make.

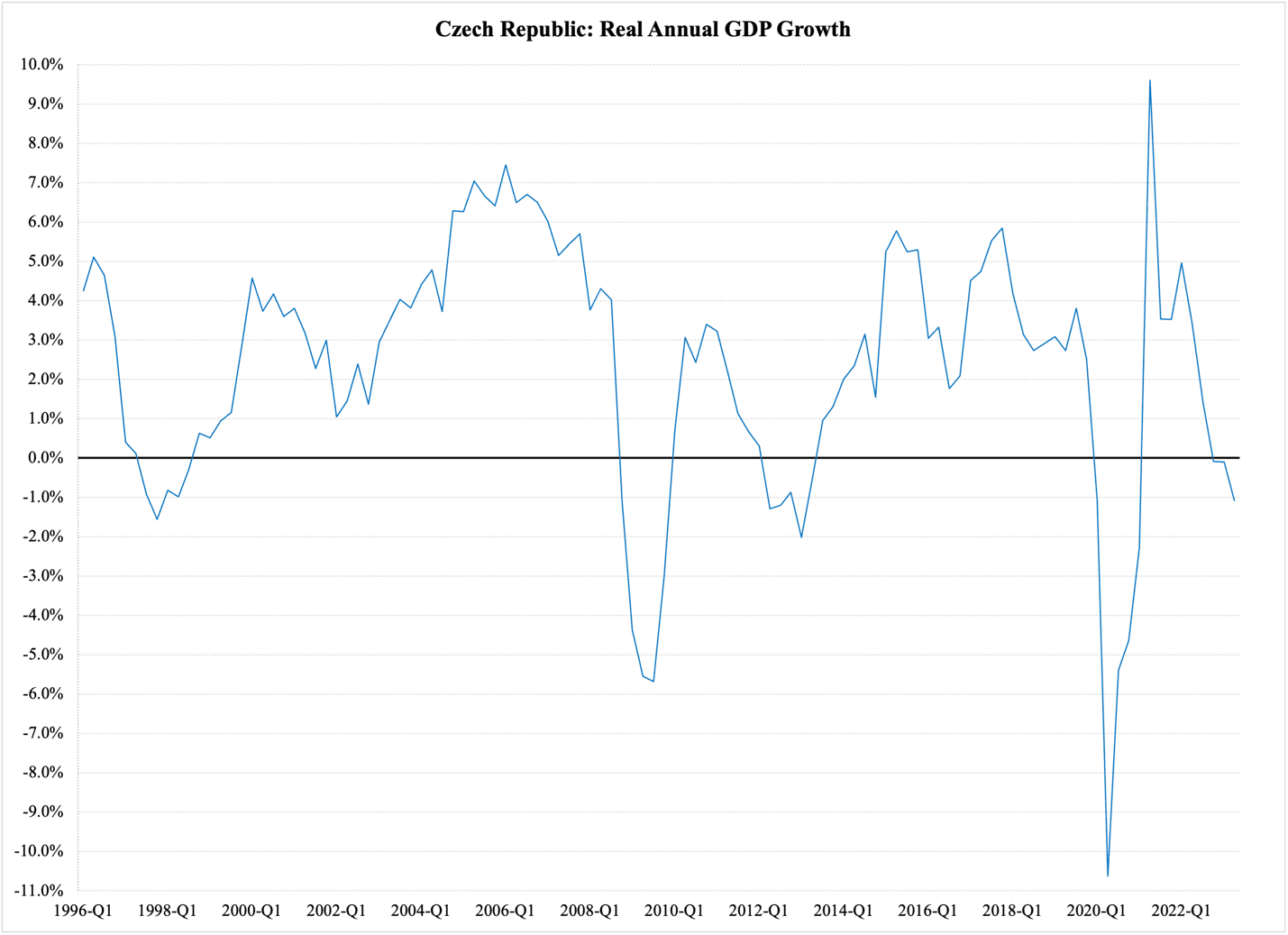

To start with GDP growth, Figure 1 reports the real annual expansion in Czech GDP since 1996. There have been two distinct growth episodes since then, one from 2000 through 2007 and one from 2o12 to the start of the pandemic in 2020:

Figure 1

On the face of it, the Czech economy looks healthy, having had several years’ worth of GDP growth in excess of 3%. This is unusual for modern, industrialized economies, but as we will see in just a moment, that growth rate is not the product of a structurally sound economy.

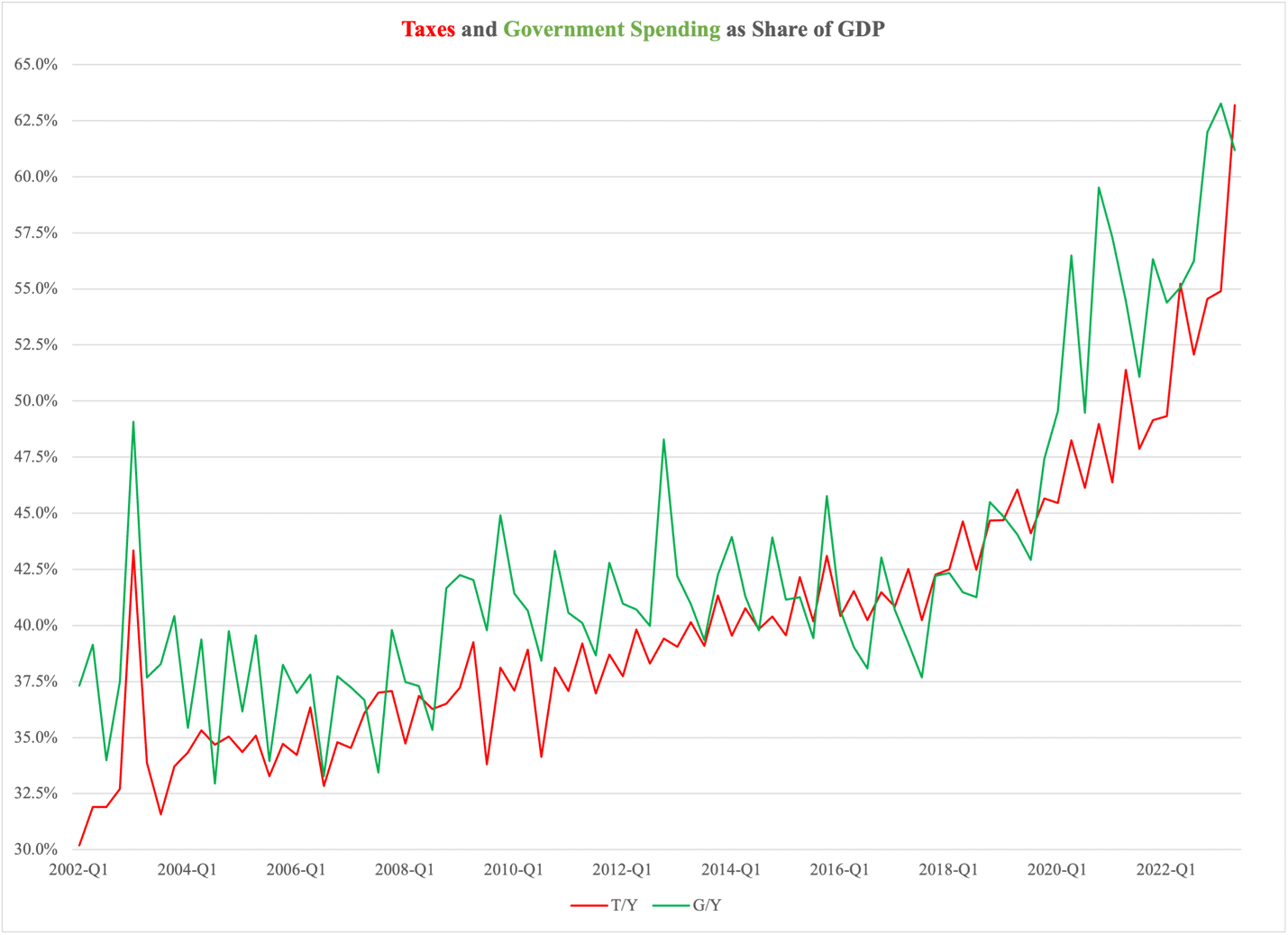

Turning to government finances, we immediately find cause for concern regarding the future strength of the Czech economy. Figure 2 reports total taxes and total government spending as a share of current-price GDP since 2002. In this period of time, the country has transitioned from a low-tax economy with a limited government—government spending does not exceed 40% of GDP until the last quarter of 2008—to a mainstream European welfare state: in the first half of 2023, government spending exceeds 60% of GDP, with taxes not far behind.

Figure 2

The growth in the size of the Czech government accelerated as a result of the 2020 pandemic, but it did not begin then. Government has been on a 20-year mission creep to gradually gobble up a larger share of the economy. This has taken its toll on economic growth:

- In 2002-2005, the Czech GDP grew by 4.1% per year, on average; at that time, taxes were at 34.1% of GDP and government spending at 38%;

- In 2006-2009, growth slowed down to 2.6% per year due to the recession that lasted from 2008 to 2010; taxes were marginally higher at 36% of GDP, with government spending at 38.4%;

- In 2010-2013, taxes crept up to 38,4% of GDP while government spending rose to 41.3%; due in part to the recession, GDP growth fell to just above 0.8% per year, on average.

The Czech economy had difficulties getting back on track again after the recession; the economy contracted for six consecutive quarters in 2012-2013. When it finally got growing again, it reached respectable levels in the 3-5% range and stayed there through 2017.

Meanwhile, the size of government had firmly parked itself above 40% of GDP. This is a problematic level, as it is statistically associated with a permanent decline in economic growth. We can see this in the last couple of years before the pandemic when the Czech GDP barely exceeded 3% growth. At the same time, government expanded toward, and even above, 44% of the economy.

There is something puzzling happening here, in the years between the Great Recession of 2008-2010 and the 2020 pandemic. Government slowly but steadily consumes a larger share of the economy, yet GDP still manages to expand at 3% per year. Normally, economies with government of this size have a hard time even reaching 2%.

The explanation for the Czech growth spurt is directly relevant for the question of the country’s euro membership.

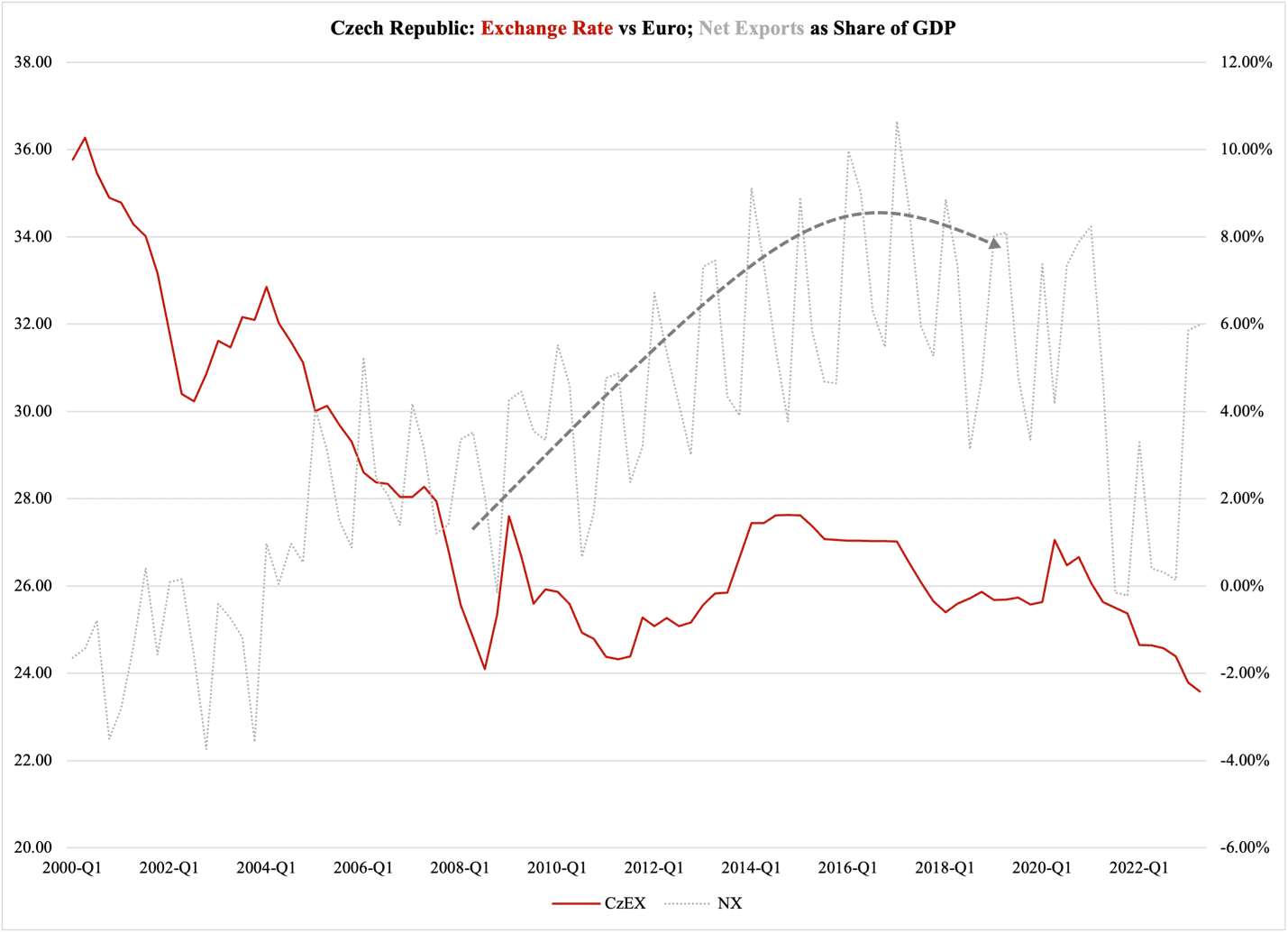

Right when the growth spurt begins, the Czech currency, the koruna, ends a multi-year appreciation vs. the euro. In 2000, it took as much as 36 korunas to buy one euro; in 2008 the rate had fallen to approximately 26 korunas/euro. Over the next decade, the exchange rate stayed in the vicinity of that rate.

During this period of time, the Czech economy underwent a noticeable structural change. There was a surge in exports: in current prices, the value of goods and services sold from the Czech Republic to the rest of the world increased from 595.6 billion korunas in the first quarter of 2010 to 919 billion korunas in the first quarter of 2015. This 54% increase in exports means that sales of goods and services to other countries solidifies its position as by far the largest single use of resources in the Czech economy.

Figure 3 reports the strengthening of the koruna (red) and the rise in exports—measured as the net between exports and imports as a share of GDP:

Figure 3

The export boom of the 2010s correlated conspicuously with a stable exchange rate. This is more than correlation or coincidence: in the previous decade when the koruna was steadily appreciating vs. the euro, there was a minor improvement in the trade balance, but it looks more coincidental than deliberate. By contrast, the rise in net exports illustrated by the dashed arrow is long and frankly impressive.

As if to illustrate the role that the exchange rate plays in this, the export boom comes to an end when the koruna begins appreciating again, right after the pandemic. It would be an exaggeration to suggest a direct causality here; the pandemic and its artificial economic shutdown disrupted normal economic relationships and mechanisms. However, the underlying point remains valid: Czech businesses built a solid presence on export markets in the 2010s thanks in no small part to their central bank maintaining a largely fixed exchange rate vs. the euro.

Given the performance of the Czech economy in the 2010s, euro accession looks like a done deal. The stable exchange rate could be said to simulate euro membership, at least insofar as the exchange rate is concerned (there are other aspects to the currency union accession that we have to put aside for now). Since the Czechs were so good at exporting under this stable exchange rate, would they not be able to do the same as part of the euro zone?

As we economists love to say: all other things equal, the answer is positive. If all that the Czechs had to worry about was to sell as much goods and services to the rest of the world—and predominantly to the euro zone—then it would be obvious that they should ditch their own currency.

However, as we economists hate to admit: all other things are not equal. We have already mentioned a major problem for the Czech economy, namely the very large government sector. It has grown to its current size because of deliberate policy decisions made by the parliament in Prague; if Czech lawmakers are like their brethren in other countries with large welfare states, they will be hard-pressed to roll back their spending. Therefore, their dependency on high taxes will remain in place.

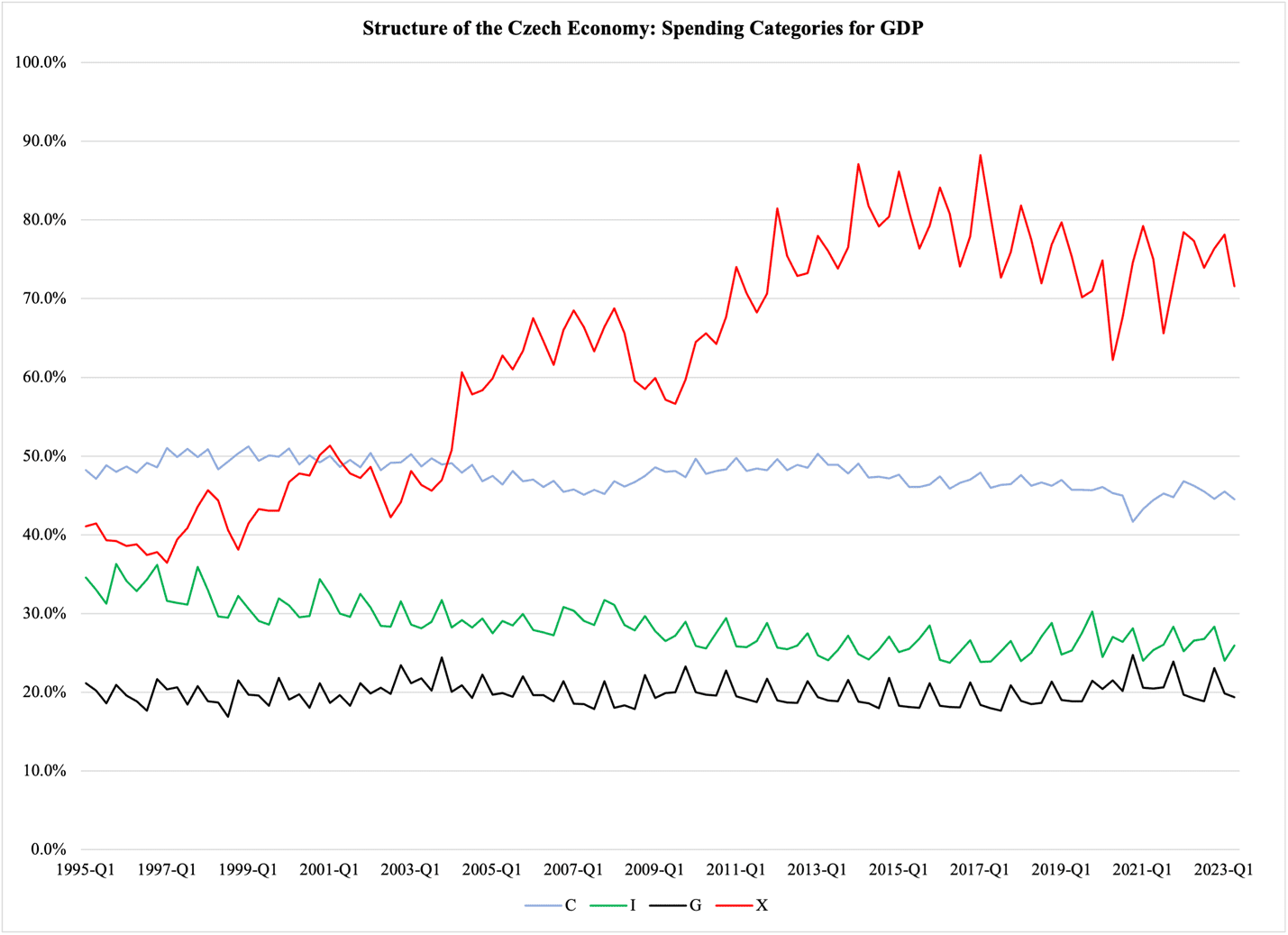

This is essential to keep in mind when we look at what will happen to the Czech economy under the euro zone. Figure 4 illustrates the trends in the four ways that we spend the goods and services we produce: exports (red), private consumption (blue), business investments (green), and government consumption (black). These are reported as a share of GDP: again, we see the exports boom from Figure 3, only here we do not subtract imports.

The big problem captured in Figure 4 is that the domestic use of resources in the Czech economy is in slow decline. Most conspicuous is the fall of private consumption well below 50% of GDP:

Figure 4

When domestic private-sector activity is depressed, even in relative terms, the tax base changes accordingly. Bluntly: when the Czechs use more and more of their resources to sell products to other countries, their tax base also becomes dependent on those other countries. Funding for schools, hospitals, and highways in the Czech Republic is increasingly at the mercy of the German, French, American, and Chinese economies.

This is only one aspect of the increased dependency on exports. There are others that we can return to in a later article; for now, let me toss a question to the euro proponents in the Czech Republic:

The Czech economy has made impressive strides in the past 20 years. The bulk of the growth in the past decade came from exports, and there is no sign that the domestic sector will benefit from the export boom. What reasons do you have to believe that the industries of your country will be able to sustain a similar export boom—ad infinitum?