Kiss of Judas (1602), a 133.5 cm × 169.5 cm oil on canvas by Caravaggio (1571-1610), located at the National Gallery of Ireland, Dublin

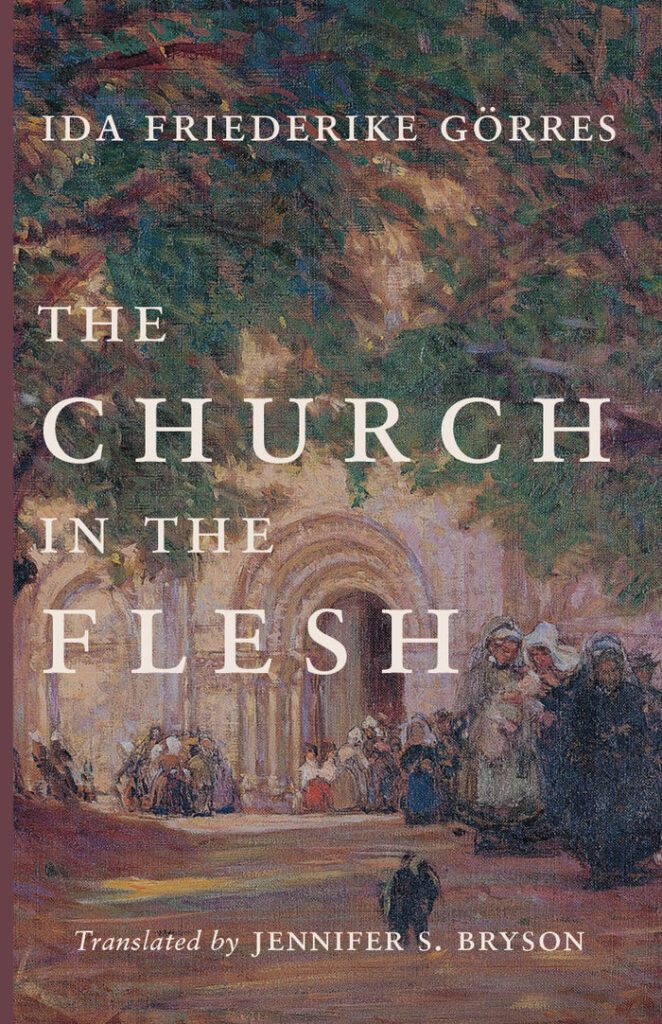

The first of a slate of new English translations has appeared from a small Catholic publishing house, Cluny Media, presenting the works of Ida Friederike Görres (1901–1971). The biographical interest of this woman is nearly matched by that of her translator, Jennifer Bryson, who promises several sequel translations in the near future. Görres belongs to a post-war moment when the Germanophone Catholic Church teemed with literary virtuosos. Uniquely, though, her mother was Japanese—she married an Austro-Hungarian diplomat in defiance of her family, giving birth to Ida Friederike, as well as her more famous brother, Richard von Coudenhove-Kalergi, and five other children. Richard was the successful propagandist for his Pan-European Union. While he sought European repristination by means of racial and political reconciliation, Ida Friederike proposed a way of liturgical and spiritual reform.

Our author studied in Vienna and Freiburg and became enamored with a potent ‘youth movement,’ which seems to have radiated, more or less, from the charismatic priest-theologian Romano Guardini, to whom many continue to be attracted. The Church in the Flesh, a series of six long epistles, lets us hear the living voice of what has since come to be considered a neo-traditionalist movement. In its blushing prime, it was indeed about flesh, youth, and, most of all, life. On the one hand, this ‘life’ accords with ambient ‘vitalist’ philosophies, and specifically in Görres’s case, the developmental theology of John Henry Newman imposes itself on her mind powerfully. Many of her peers pitted ‘life’ against ‘structure,’ fresh ideas against the constraints of classical theology or political forms. While Görres sometimes shows her inclination in this direction, wanting, for example, to “let the Church’s real face shine again without makeup,” she will just as quickly come to the defense of life-giving structures. The antinomy, for her, is not life and structure, but life and death.

Her letters to struggling Catholics sound now, in hindsight, like letters to those about to die. The first five letters are pitched to cultured despisers of one kind or another, whose variously earnest and disingenuous struggles Görres takes absolutely personally. She has none of the detachment of online apologists, who now produce the same ‘arguments’ she does with an increase in technique that matches the development of many other weapons since the early 1900s. What comes across, instead, is an intense desire to show how much more she has already known every doubt of Church practice and has judged with sovereign contempt all half-hearted or false piety and come out refined by a love that could only be supernatural—since it leaves no man standing yet forbids none to enter its inner chamber.

Bodily unity is only a metaphor in political thought, but for the Church it is all too real. Görres perceives the Church as a ‘survivor’ of both human vice and divine love. It suffers from its perpetual youth and hulking age, and “what has been lost reminds us in dreams and neurotic symptoms that it must be found again and reassimilated.” For Görres, the life invisibly binding Christians into a body makes discipline necessary; the Church cannot be expected to publish requirements of belief alone without demanding muscular moral exercises as well. “We all know people whose soul is reminiscent of a body with polio,” she writes, and “as a horribly small, stunted, and unusable hand hangs on a strong, fully grown man’s body,” her peers hung onto the mountain-moving force of the Catholic faith and did not see how they were about to be thrown off or torn away from it. She wanted them to eat, breathe fresh air, exercise, and take medicine.

As a gardener of spiritual realities, she was offended by the inexpert advice of those who prescribed a faith-free ethics for Europe:

Here, as in other areas of truth, it is incumbent on the Church to displace such anemic, crumbling pseudo-ethics, which are dead on arrival, at their premises, with the authentic growth of a healthy and flourishing morality; at the same time, the still-living and beautiful sprouts, so-called garden escapees, thrive beyond the periphery, to be replanted in the deep mother-soil of their origin.

Some chafe under the fanciful vocabulary of “flourishing” that characterizes certain ethical discourses, whether because of its imprecision or its image-bound character. Görres would obviously be unfazed by the objection and wants specifically to talk with her epistolary friends about not only a metaphorical but a sexual fruitfulness, as well as the “undivided love” of virginity and its weight in the Church’s strangely abundant body. She and her husband were unable to conceive; her voice reaches out with an iron maternal will to reproduce her spiritual form in the ear of her reader.

If you have heard of Görres already, it is probably as the foundress of modern hagiography, with her biography of St. Therese of Lisieux being the most famous. The sixth letter, “Church of the Saints,” answers an interlocutor’s question: “Why do I devote myself so zealously to studying the saints?” This letter dwarfs the other five in quality, offering a personal justification of her life’s work but also a zealous creed about being human. When is one truly herself, truly alive? Can you see an indestructible life in another, or are you haunted by the conviction that you are surrounded by shadows of men, fratricidal monsters, and repetitions of dangerous vacuity? For Ida Görres, the only hope for wounded nature is that it be engulfed in grace, something not natural yet nevertheless “subject to the inexorable laws of growth.” To the heart, the mind that desires nothing but death, grace promises new desire, not bound by neural or libidinal channels:

It is a tremendously stirring spectacle of how this stream of longing obedience swells and searches for a path and breaks fresh ground, at one point quiet and hidden, only recognizable by the blessed fertility of its banks, at another as roaring rapids, dangerous and flooding, then again tamed, channeled, dwindling, and seeping into “bourgeois life,” while the land all around becomes desert, then again, like rivers in a rocky landscape breaking up from underground depths, invincible, full of promise.

The Church in the Flesh insists on “the nearness of the world of carnage,” a phrase Görres borrows from Ernst Jünger, and the greater nearness of God: His Blood is running already in human veins, spilling out all the time with its “blessed fertility.”