On Friday January 26th, The DC Weekly reported that Jamie Dimon, CEO of the big American Bank JP Morgan Chase,

sounded the alarm on the escalating US debt and warned of a potential economic crisis if the issue is not addressed promptly. Dimon compared the current state of the economy to that of 1982, highlighting the significant increase in [the] debt-to-GDP ratio

Dimon is not the first chief executive officer of a big corporation to voice his worries about the U.S. government’s bad fiscal record. On January 17th, CNBC quoted David Solomon, CEO of Goldman Sachs, as being “very concerned about the growing debt,” which he characterizes as “a big risk issue.”

These debt worries are coupled with growing concerns about an American recession. A day after the CNBC article, I analyzed a speech by Christopher Waller, a member of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve. I explained that: “In effect, Waller is predicting a recession.” While I disagreed with this outlook, I also noted that

if the GDP numbers for the fourth quarter come in at about the levels Governor Waller predicts, namely closer to 2% year-to-year growth, and if CPI inflation for January is below 3%, then we can raise the recession flag for the U.S. economy.

The Fed governor’s worry about a recession is understandable, especially in the context of the concerns that the bank CEOs are voicing. A recession would wreak havoc on the federal government’s debt and its ability to continue to borrow money.

Fortunately, the U.S. economy is still doing well. The Bureau of Economic Analysis, an outfit under the U.S. Department of Commerce, just released its first estimate of the U.S. gross domestic product for the fourth quarter. Their numbers show no immediate signs of a recession, although there is one little tweak that makes me predict a recession to begin in the first half of 2024.

Adjusted for inflation, GDP grew by 3.1% in the fourth quarter of 2023 compared to the same quarter in 2022. The press release from the BEA says the growth rate was 3.3%, but their number is based on an annualized, seasonally adjusted figure that does not very well represent what is actually happening in the economy. (Please don’t ask me why the BEA uses this contrived number—I have torn my hair out over that question for 22 years.) The following analysis is based on the BEA’s national income and product accounts (NIPA) table 8.1.6, which reports the raw GDP data, adjusted only for inflation.

While GDP grew by 3.1%, fixed business investments (capital formation) increased by almost 3.3%. Private consumption expanded by 2.3%.

The ‘raw’ GDP number that I report here may be 0.2 percentage points lower than the adjusted number that the BEA puts out, but it still represents a strong economy. If we don’t count the recovery from the economic shutdown during the pandemic—which we shouldn’t since the shutdown was an artificial event—this is the strongest GDP growth number since the fourth quarter of 2019. Back then, the economy grew by 3.3%.

It is not ideal for a strong, resilient economy to have consumer spending grow more slowly than the economy as a whole. Nevertheless, that is where we are; for now, it is not much of a concern, especially since private consumption is growing at a steady pace: the average annual rate for 2023 is 2.27%. Again, it is not a great number, but it is acceptable, and definitely no sign of a recession.

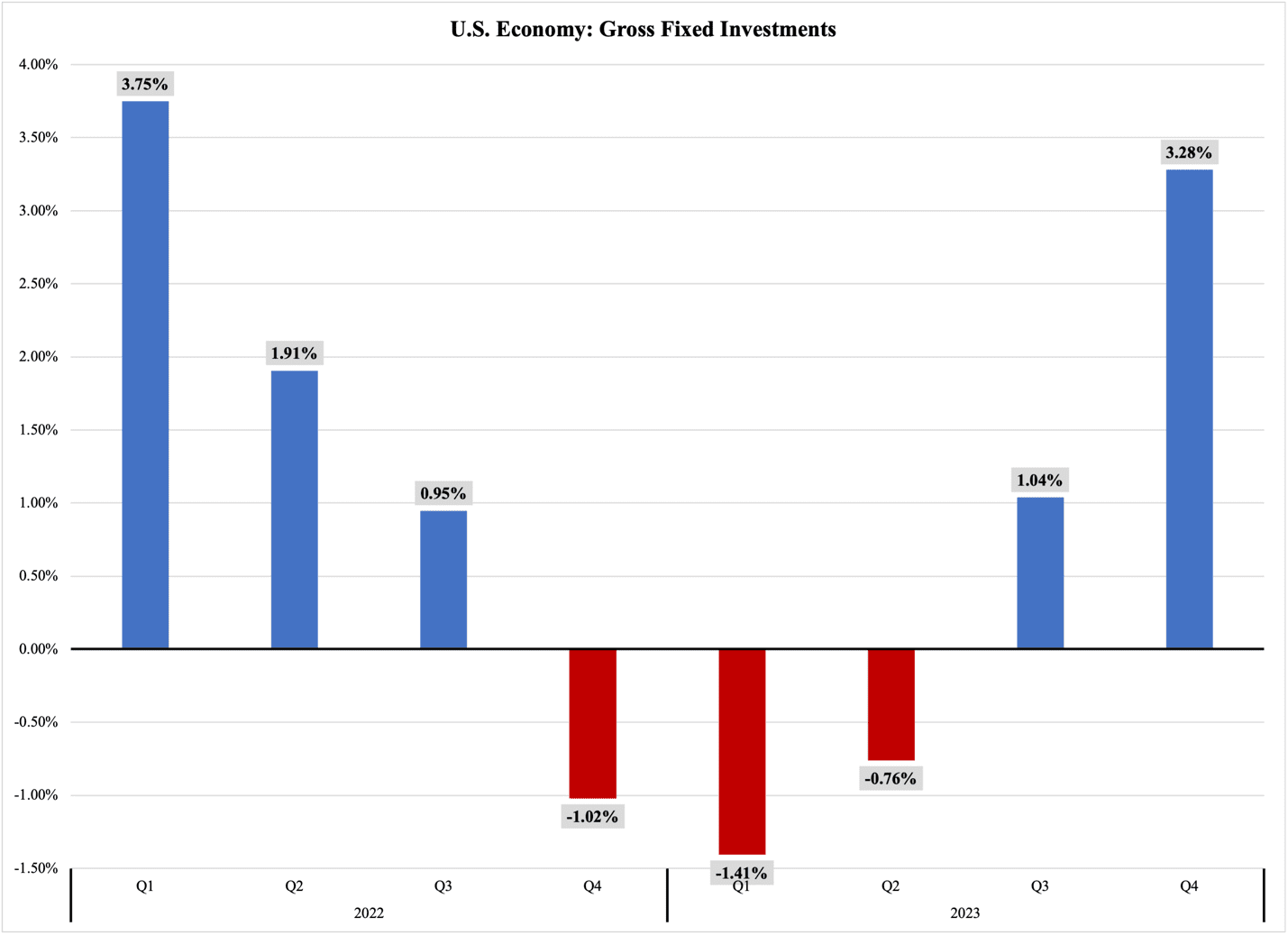

The data on investments is even more positive. Here are the real annual growth rates for gross fixed business investments in the past two years:

Figure 1

Most of the investment subcategories also look healthy. These are all inflation-adjusted numbers:

- Nonresidential investments, which includes structures (offices, factories, processing plants, warehouses, etc.) and all kinds of business equipment, increased by 4.2% year over year; the increase in spending on structures was 15.6%;

- Spending on residential structures—also known as homes—increased by 0.2%; this is a small number, but it is a significant turnaround after home construction declined for seven quarters in a row.

Now for the little tweak that makes me wonder if we aren’t going to see a recession soon after all. Spending on business equipment, i.e., all the things that businesses use in their production, fell by a minuscule 0.1% in the fourth quarter last year. This decline came on the heels of the third quarter’s -2%.

Businesses also moderated their spending on so-called intellectual property products, primarily computer software. This category increased by 2.7%, the lowest growth rate since the third quarter of 2010.

When businesses reduce spending on equipment, they have reached the point where they are worried about over-investing, i.e., creating excess capacity. Another way to put this point is to say that when equipment investments have peaked—which could be what we are witnessing—then businesses are worried that their sales will not be strong enough to put all their equipment to work.

The slowdown in business purchases of equipment and software is no real source of worry at this point. However, it suggests that we will see a downturn in a more important business-cycle indicator in the first quarter of this year. When businesses have filled their structures with ‘tools’ of all kinds, from furniture and screwdrivers to robots and advanced computer programs, they no longer need to expand spending on new structures.

In other words, we should expect that the growth rate in business spending on structures, which again was 15.6% in the fourth quarter of last year, will be significantly weaker in the first quarter of this year.

For reasons I will cover in a coming article, business investments in structures are a very good indicator of where the business cycle is heading. It has marked the bottom of recessions going back to the 1950s.

Again, more on that in a coming article. For now, we can conclude that the Federal Reserve and everyone else predicting a U.S. recession have not yet been proven correct, but that if they keep crying wolf through the first half of 2024, they will be proven right.