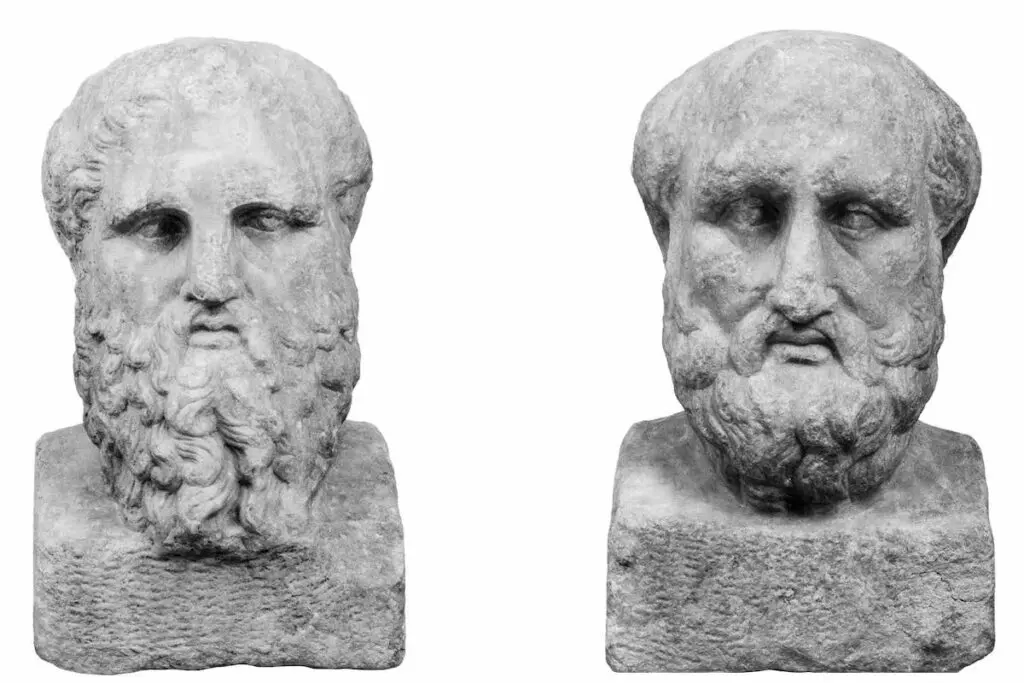

A representation of Plato (left) and Aristotle (right) from a two-headed bust—“joined back to back, ears just touching, on two connected necks,” according to museum notes—of the late 2nd century made of white marble with blue veins. The bust measures 38 cm in height. The head of Plato “has a prominent brow, a short, strong nose, and deep-set eyes. The face is asymmetrical …. The curls of his beard are long and well defined.” In contrast, the head of Aristotle “bears his characteristic bald crown and a long nose that starts to narrow at the bridge and widens at the nostrils. His eyes are visibly aged.”

Images and descriptions courtesy of the Getty Museum.

Alexandre Lacassagne, the French forensic pathologist who published a book on tattoos in 1881, would have been astonished at, and puzzled by, the explosion of elaborate and professional tattoos in the general population in the last three decades.

It is surely remarkable that the best known Girardian of our time—namely, Peter Thiel—wrote an essay which was meant to point to the superiority of René Girard’s analysis of modernity over those of other contenders, and called it “The Straussian Moment.” Why not the Girardian moment? Why does Strauss occupy the titular and hence in some ways most conspicuous place in Thiel’s consideration of the foundations of modern politics? A brief reconsideration of Thiel’s justly famous essay (arguably famed for its title more than anything) may help us understand why in politics there is only the Straussian moment, even if it is coupled with prudent hope and faith in a peaceable world—and who could doubt that it should be?

The final words of Thiel’s essay on the “Straussian Moment” juxtapose two alternatives to the modern, desacralized, unserious, and predominantly commercialized Western world: “the limitless violence of runaway mimesis or the peace of the kingdom of God.” This can be compared to another juxtaposition, that of The City and Man, the name of a book by Leo Strauss that Thiel cites throughout and that is used for his final citation. The first, apocalyptic alternative is Girardian and Christian. Strauss’, by contrast, is classical. Whether we have limitless violence or peace depends partly on whether “the Christian statesman or stateswoman” wisely “side[s] with” peace after weighing “the correct mixture of violence and peace.” Perhaps a wise Christian statesman or stateswoman can at least restrain the hell of limitless violence, if not inaugurate the messianic era in which peace has replaced division between friends and enemies.

Strauss’ The City and Man has an entirely different mood and tenor, far from either heaven or hell on earth. Compare the nearest parallel in Strauss’ book to the complete chaos of runaway violence. In his chapter on Thucydides, Strauss writes that, in Thucydides’ work, “we become at once immersed in political life at its most intense, in bloody war both foreign and civil, in life and death struggles.” Thucydides shows us all the brutal particulars of politics. But “most of the time the city is at peace” and “not immediately exposed to that violent teacher War”; and in peace it can practice “moderation and obedience to the divine law.”

The political historian and the political philosopher do not have “visionary expectations” about what the divine law can accomplish in a political setting: messianism is not classical. As Strauss writes: “The belief in progress must be qualified with a view to the fact that human nature does not change.” No change in human nature, no progress beyond politics to the peace of the kingdom of God. Not in this life.

It may look, then, like the conflict between Girard and Strauss is simply the old conflict between ‘Jerusalem’ and ‘Athens,’ a conflict Thiel discusses in his essay in those terms. The Messianic Era is at home in ‘Jerusalem’; unchanging human nature, in ‘Athens.’ But does that schematization help us make sense of Thiel’s conjecture that “[in] the debate between Strauss and Girard, perhaps the key issue of contention can be reduced to a question of time”?

Yes and no. For Thiel, the question of time concerns the problem of “when” the “highly disturbing knowledge” of the violent heart of politics will “burst upon general awareness.” He has in mind the concern that politics will end if the mechanisms of violence at its heart are unconcealed. Girard does not share this concern because, for Girard, “there will come a day when there is no esoteric knowledge left.” There does not come such a day for Strauss, however. The chasm separating the wise from the vulgar is not crossed over time. The conditions that require a philosopher to write esoterically change as little as does human nature. In the conflict between Girard and Strauss, ‘time’ is thus at issue not in the sense of ‘when’ but rather in the sense of ‘whether, if at all.’ As Strauss said in his debate with another defender of the political significance of ‘time’ or ‘history,’ Alexander Kojeve, “[p]hilosophy in the strict and classical sense is quest for the eternal order or for the eternal cause or causes of all things. It presupposes then that there is an eternal and unchangeable order within which History takes place and which is not in any way affected by History.”

Time is at issue as the repudiation of this presupposition. Properly understood, if there is a “Straussian Moment,” it is the eternal moment within which political history occurs. It can be likened in the following way to Plato’s cave allegory. That allegory depicts a permanent structural feature of our nature with respect to its education and lack of education, and a permanent structural feature of political life, within which we can identify three if not four stages: the stage when all we see are shadows, the stage when we are made aware of the fire against whose light the shadows are cast, and the stage when we exit the cave altogether and learn to see by the light of the sun (and finally, the return to the cave). There is ‘history’ as we pass through these stages: an ascent and descent. But the stages themselves are structurally fixed. There is not ‘progress’ in the sense that the bright light of the sun could ever replace the role of the fire and become the sole source of light for those who prefer the shadows.

Similarly, the structure of politics that Strauss discusses largely through his commentaries on classical political thinkers is not one that changes fundamentally. In his book on Machiavelli, to which Thiel pointedly refers, Strauss writes that Machiavelli, the first modern, “does not bring to light a single political phenomenon of any fundamental importance which was not fully known to the classics.” The basic political phenomena may be distorted, suppressed, forgotten, or ignored. The emphasis in their presentation may shift here or there depending on circumstances and the intentions of a given author. But they remain essentially the same. History or time is deprived of its revelatory role.

Accordingly, there is no notion in Strauss of the role of fate or destiny in politics, although the classical notion of chance remains (so much so that modernity can be characterized partly by the non-classical intention of conquering chance). How, then, can Thiel suggest that “for a Straussian, there can be no fundamental disagreement with Oswald Spengler’s call for action at the dramatic finale” of The Decline of the West, when that call for action concerns precisely “Destiny,” “historic necessity,” and “the fates”? What is decisive for Strauss’ account of “the city and man” is, above all, the philosophic quest for truth, a quest that is ever spurred on by the awareness of ignorance or lack, and by an erotic drive to possess the beautiful and needful. And Spengler? He writes in his “dramatic finale” of “life,” “blood,” and the “will to power”—but not of wisdom and the quest for it—i.e., philosophy. Strauss and Spengler are poles apart, even if Spengler does recognize Socrates, in passing, as the peak of one high culture among others.

The Straussian use of Girard would have taken advantage of the Christian dimensions of Girard’s thought at time when a prudent and statesmanlike re-Christianization of political discourse was deemed appropriate. Let us not forget that Thiel’s essay begins by stating that the attacks of September 11th have called the foundations of the modern West into question. How? The modern Western world is a deliberately secularized Christian world that has been moved away from existential concern with the deep, serious dimensions of human life—like those addressed by religion—towards commercialism and a doctrine of rights based on circumventing the difficult question ‘what is man’ (not to mention the related and ‘all-important’ question that, as Strauss put it in his final line of The City and Man, “is coeval with philosophy although hers do not frequently pronounce it—the question quid sit deus?”).

By moving away from the serious dimensions and all-important questions, the apostles of modernity may have believed they were moving away from the deepest sources of conflict, as Thiel explains through his commentary. But Strauss once wrote as follows:

Agreement at all costs is possible only as agreement at the cost of the meaning of human life; for agreement at all costs is possible only if man has relinquished asking the question of what is right; and if man relinquishes that question, he relinquishes being a man. But if he seriously asks the question of what is right, the quarrel will be ignited … the life-and-death quarrel: the political—the grouping of humanity into friends and enemies—owes its legitimation to the seriousness of the question of what is right.

We cannot relinquish our humanity: modernity is not enough. But neither can we accept Schmitt’s agonistic re-politicization of the West vis-a-vis Islam, Thiel argues, since that risks “doing away with everything that fundamentally distinguishes the modern West from Islam” and would therefore be a “Pyrrhic victory.” Western re-politicization would amount to a kind of mimetic rivalry with the Islamic world, and mimetic rivalry leads to runaway violence. So, we need the political, but not in the way Schmitt gave it to us. With Girard, however, we get a political theology (“Christian statesman or stateswoman”) that is aware of mimetic rivalry and that aims to side with peace. What would distinguish the Straussian use of Girard from Girardianism pure and simple would be the recognition—or at least the well-founded suspicion—that the arcane truth of the basic human situation is not about to “burst upon general awareness”—that the katehonic nature of politics and not the messianic overcoming of the appropriate field of action for the philosophic statesman.

Thiel has said elsewhere that, “only by seeing our world anew, as fresh and strange as it was to the ancients who saw it first, can we both re-create it and preserve it for the future.” But how do we see the world as fresh and strange as it was to the ancients when we have inherited so many ways of looking that stand between us and the original phenomena, including the long history that interprets that world for us conceptually? Strauss had an answer. He says that “the world as it is present for, and experienced by,” a “natural view … had been the subject of Plato’s and Aristotle’s analyses .… Therefore, if we want to arrive at an adequate understanding of the ‘natural’ world, we simply have to learn from Plato and Aristotle.”

That means in part unlearning what we believe we know through hearsay, tradition, and history; it requires a careful return to what they wrote, free or gradually freed from preconceptions. Strauss does not say quite what Thiel suggests, that we must “re-create” and “preserve” that world. But he does say that “what is decisively important is that we first learn to grasp their intention and then that their results be discussed,” in order that we better understand “the quarrel between the ancients and the moderns.”

Thiel must know that he was bending the truth when he wrote that, “[u]nlike Strauss, the Christian statesman or stateswoman knows that the modern age will not be permanent, and ultimately will give way to something very different.” Strauss never argued or implied that the modern age will be permanent. The tendency of all of his writings is precisely to put the classical alternative back on the scales—predominantly through a recovery of Plato and Aristotle, the other two authors besides Thucydides that he discusses in The City and Man.

This essay appears in the Winter 2024 edition of The European Conservative, Number 29:78-80.