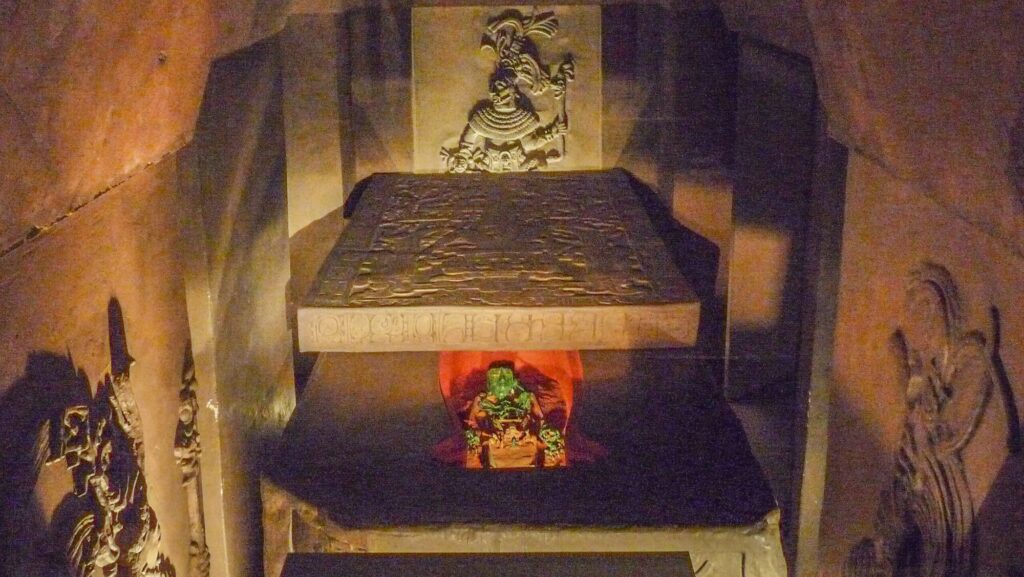

Reproduction of the mausoleum of Pakal in Mexico City. The original tomb was resealed and hasn’t been reopened since. Photo by El Comandante, CC BY-SA 3.0 Deed.

Attempting to expound someone else’s thought is always a high-risk endeavor. But since I recently declared Dalmacio Negro Pavón the most significant political thinker in Spain in recent decades, with all due caution, I will outline what I consider to be some of the interpretive keys to Negro Pavón’s thought.

With its basis in research, classification, and interpretation of various traces and artifacts, scientific historiography focused on the study of antiquity avoids excessively speculative discussions about those architectural monuments whose existence and significance are difficult to explain. Although he was not actually a professional historian, one scholar who attempted to propose plausible explanations for such remnants of the past was the mathematician and logician Anton Dumitriu. In Philosophia mirabilis: An Essay on an Unknown Dimension of Greek Philosophy (1974), a work virtually unknown to the Western audience, he mentions the ‘Forgotten Stone’ from Baalbek (Lebanon) estimated to weigh about 1700 tons; the ‘Gateway of the Sun’ at Tiahuanaco (Bolivia); the tombstone from the pyramid at Palenque (Mexico); giant stone spheres located in Costa Rica; and other such wonders of antiquity.

Those who have read authors specializing in ‘paleo-astronautics,’ such as the Swiss writer Erich von Däniken, have surely heard about these monuments. They have been—and, in some cases, still are—considered by ufologists as irrefutable evidence of contact between ancient terrestrial cultures and civilizations from outer space. In fact, many of these stone-carved ‘documents’ have remained shrouded by ignorance, superstitions, and distorted interpretations. By rejecting outright the theories that insist on finding extraterrestrials in the past (when such a thing has not been achieved in the present), Anton Dumitriu opens the path to a research worth pursuing. It is worth noting his interpretation of the mentioned monuments and others like them:

I have quoted only these indisputable stone documents to draw a single conclusion, formulated in two parts: 1. Although our planet bears the unmistakable signs of fantastic achievements, humanity has lost their memory and cannot explain their appearance thousands of years before the technical civilization of our era; 2. The hypothesis of a linear evolution of civilization is refuted precisely by the existence of these enigmatic monuments, signs of ancient advanced civilizations that, in their development, reached a catastrophic point and disappeared, leaving behind certain traces but without any continuity with later civilizations.

The question is as follows: can we simply accept that these civilizations were capable only of cyclopean technical achievements and not of ideas and concepts equally grandiose in abstract order, but which have vanished without a trace because we do not know—at least until now—their writing and inscription on the remaining monuments?

The question is rhetorical, as, based on certain pertinent observations, Dumitriu argues that it was impossible for a civilization that produced such monuments not to possess a highly significant spiritual culture entirely comparable, if not superior, to the technocratic civilization of our era. However, Dumitriu’s arguments imply a conception that the entire modern view of history ignores, when it does not violently reject it: the world, the cosmos, and humanity may not have necessarily undergone evolution; on the contrary, a multitude of traces and archaeological evidence lead us to the idea of a descending meaning, a devolution of history.

The ancient idea of degradation and the degeneration of the world and humanity, similar to the aging of the human being, stems from the awareness of the growing gap that separates Heaven from Earth—the spiritual, transcendent, metaphysical world and the material, immanent, palpable world. Succinctly, I will mention only a few of those major crises in pre-Christian cultures that supported this perspective: ancient Hindu thinkers realized the ineffectiveness of ritual formulas; Buddhism displaced the Vedantic tradition; Taoism was replaced by Confucianism; contemporaries of Socrates lost the values of Minoan royal culture, replacing them with imported deities like Apollo and Dionysus; Plato noticed the drift of the Homeric tradition, which, instead of being truly inspired by gods (or muses), became a mere patchwork of fragments and poems abundantly embellished by rhapsodes as they pleased; and, Latin culture was shaken in the 2nd century B.C. by the Bacchanalian process, and ultimately collapsed under the weight of Hellenistic syncretism.

These are just a few signs of the times that justify a perspective on history that conceives it as being characterized not by evolution but, on the contrary, by decline (or devolution), in a gigantesque picture that presents the four decreasing ages of the universe in Hesiod’s mythology: the Golden Age, the Silver Age, the Bronze Age, and the Iron Age. A few millennia later, within the context of Christian theology, Saint Augustine’s theory of history—rooted in the prophecies of Daniel and the apocalyptic visions of the Apostle John—also recognizes the descending (or involutive) sense of history.

Observing that the idea of devolution has been marginalized to the point of exclusion from modern culture raises the question of why such a distortion of history—involving the efforts of so many ‘enlightened’ intellectuals, including Auguste Comte, Charles Darwin, Karl Marx, and Alfred R. Wallace—was necessary. Suffice to say that no one consciously participated in the process. There is no need to imagine cabals and conspiracies designed to hide the truth. The reality is much simpler: the truth itself becomes opaque or is distorted when the members of a culture lose the understanding and perspective that allows them to decipher the profound meanings of man and the cosmos. To elaborate, I will briefly present one of the archaeological monuments mentioned by Anton Dumitriu: the tombstone of the sarcophagus of King Kʼinich Janaab Pakal I (603–683). I have chosen this artifact because it was mentioned during a 2019 episode of Joe Rogan’s show in which he questioned the meaning of the bas-relief on King Pakal’s cenotaph.

30 years after Howard Carter and Lord Carnarvon experienced an Indiana-Jones-style thrill when they unearthed the tomb of King Tutankhamun, another archaeological discovery was set to send shockwaves through the scholarly world. In 1952, after leading over 10 years of systematic excavations at the Palenque site in Mexico, archaeologist Alberto Ruz Lhuillier (1906–1979) was to see his efforts richly rewarded.

With the support of the Mexican government, which granted the necessary permits, Lhuillier took a keen interest in one of the most spectacular monuments ever discovered in Central America: the ‘Temple of the Inscriptions,’ named so due to the numerous hieroglyphs carved on its interior walls. Facing south, the magnificent structure is surrounded by a dense jungle located in the most famous archaeological site between Sierra and Chiapas, in southern Mexico. A noteworthy aspect is the number of steps on the staircase leading to the temple platform: sixty-nine, precisely the number of years in the reign of the one for whom the monument was erected, King Pakal.

Drawn in 1948 to a series of holes in the temple floor, which is at a height equivalent to that of a 7-story building, Lhullier discovered a stone slab under which lay a mysterious staircase covered in debris. Through feverish work, the archaeologist and his team cleared the staircase and descended to the base of the pyramid. There, they discovered a colossal sarcophagus. Covered with a slab weighing nearly six tons, the tomb contained the remains of one of the most renowned kings in Mayan history: King Kʼinich Janaab Pakal I, who ruled from A.D. 615-683.

Both King Pakal and the discoverer of his remains, Alberto Ruz Lhuillier, were to become far more famous than even the most optimistic observer could have imagined. Their fame was not only due to the efforts of historians dedicated to the study of the Mesoamerican world, but also because of a controversial author specializing in ‘paleo-astronautics,’ named Erich von Däniken.

Born in 1935 in Zofingen and raised in Fribourg, in a Catholic family, von Däniken had a remarkable history. Without ever completing his studies, he became a hotelier in his native Switzerland at the age of only 19. Despite the administrative role to which he quickly ascended, he continued to pursue his passion for ancient cultures and, in particular, the investigation of the most controversial archaeological traces since his adolescence. This led him to write a book, Chariots of the Gods? Unsolved Mysteries of the Past (1968), which became one of the best-selling works of the last decades of the 20th century. The volume drew the attention of a wide, non-specialized audience to real issues raised by archaeological discoveries. Translated into numerous languages and sold in tens of millions of copies, Chariots of the Gods? represents a perplexing example of the inadvertent manipulation of history. Considering von Däniken’s Catholic upbringing, it is also a typical instance of the secularization of Christian Credo. Despite these aspects, there are positive aspects to the work that should not be overlooked.

With a tone both prophetic and enigmatic, Erich von Däniken purports to reveal a great secret: in ancient times, Earth was visited by extraterrestrials. Using rhetoric that obsessively repeats the same theme, he constructs a hermeneutic based on this singular presupposition, regardless of the arguments offered by mainstream archaeologists. All historical sources, all archaeological traces, and especially the ancient sacred and mythological texts of humanity, are interpreted through this lens: Earth was visited by extraterrestrial beings. Eager to gather as much evidence as possible, a discovery as significant as that at Palenque could not escape his notice.

The lid of the sarcophagus covering the remains of Hanab’-Pakal I is adorned with a well-preserved bas-relief featuring an uncommon wealth of detail. The image depicts King Pakal entering the subterranean world of the dead, enveloped by the roots of the sacred Ceiba tree. The ancient Maya believed that these roots, anchored in the center of the Earth, connected the three realms of the entire cosmos: the underworld, the Earth, and the heavenly paradise. In the symbolic vision of their ancient thought, the sacred tree was also the bridge facilitating communication between the world of humans and the world of spirits and gods.

For von Däniken, the original and genuine meanings of Mayan mythology are irrelevant. Through his paleo-astronautic worldview, he can only see what his own perspective allows. After claiming that archaeologists are mistaken in their interpretation of the tombstone of Hanab’-Pakal, he proposes an alternative viewpoint: the stone must be viewed from the side, along its longer edge, rather than the shorter side. According to this visual angle, the king is not, in fact, curled up on his back facing the lofty paradise of the Ceiba tree. Instead, he is curled forward, like a motorcyclist. However, the multitude of threads surrounding him lead von Däniken to observe: he is an astronaut! Dressed in a suit similar to those worn by modern cosmonauts, with an oxygen tube entering his nose, he can only be an extraterrestrial.

But von Däniken doesn’t stop there: he sees the flames of the reactor, the fuselage of the spacecraft, and, in short, all of the accessories of a spaceship piloted by the mysterious passenger. His followers go even further. Mihai E. Şerban, a Romanian author who adopted his ufological theory, claims that the skeleton in the tomb is much taller than the natives: 1.70m compared to (at most) 1.54m. Obviously, all these pseudo-scientific speculations lead to a single conclusion: we are dealing with an extraterrestrial who is, in fact, the true ancestor of the human species.

Paradoxically, ancient mythology often refers to supra- (or extra) natural, non-earthly beings. After all, characters considered by some to be aliens coming from the cosmic abyss, are, in a certain sense, extra-terrestrial. Members of ancient cultures, for the most part, believed that the material, physical world, in which we live, is mirrored and inextricably linked to another, immaterial world, in which our souls reside. For them, in a certain sense, that immaterial world was even more real than the material world dominated by physical laws. The passage through death and the journey of the soul ‘beyond’ were what particularly interested them.

The members of Mayan culture were no exception. What they depicted through the sculpture on the tomb of King Pakal I does truly show a journey to another world. However, it is not another material world but one of the spirit, recognized by all the ancients, wherever they may be: the Greeks of Homer and Socrates, the Egyptians of Pharaoh Tutankhamun, the Jews of Moses, the Chinese of Laozi, or the Hindus of Patañjali.

Paradoxically, we can answer Joe Rogan’s question by stating that, indeed, the figure on the tombstone in the Temple of the Inscriptions at Palenque is an astronaut, in the sense that he is a navigator through the cosmos. However, he is not travelling through the material cosmos, but rather through the one the Maya believed to be eternal and imperishable—the unseen cosmos of a spiritual nature that is invisible to our corporeal eyes.

Of course, there will be those who immediately ask for the location of this unseen world, this unseen cosmos. Others, even more categorical, will smile, rejecting its possibility or viewing it with skepticism. I hasten to assure them that there are serious answers to such questions—clear, complete, and coherent answers. Far from outer space and the edges of the cosmos, those answers can be found right here: all one needs to do is pick up and read the right book.