Dear Townies is an extended letter to urban dwellers, from a pair of rural dwellers who want the case for the countryside to be better understood. It could not be described as a love letter, because the tone is one of exasperation: it expects that those who do not live in the countryside should learn more about it before they start preaching from the towns about how the countryside should be run. Better still, they should probably stop preaching altogether.

The first author, Dominic Wightman, is a countryside dweller and editor of Country Squire Magazine. The second author is a frequent contributor to that magazine. Both bring to that publication, as they do to this book, a caustic wit and a sense of irony that verges on the hilarious. The book is replete with memorable passages.

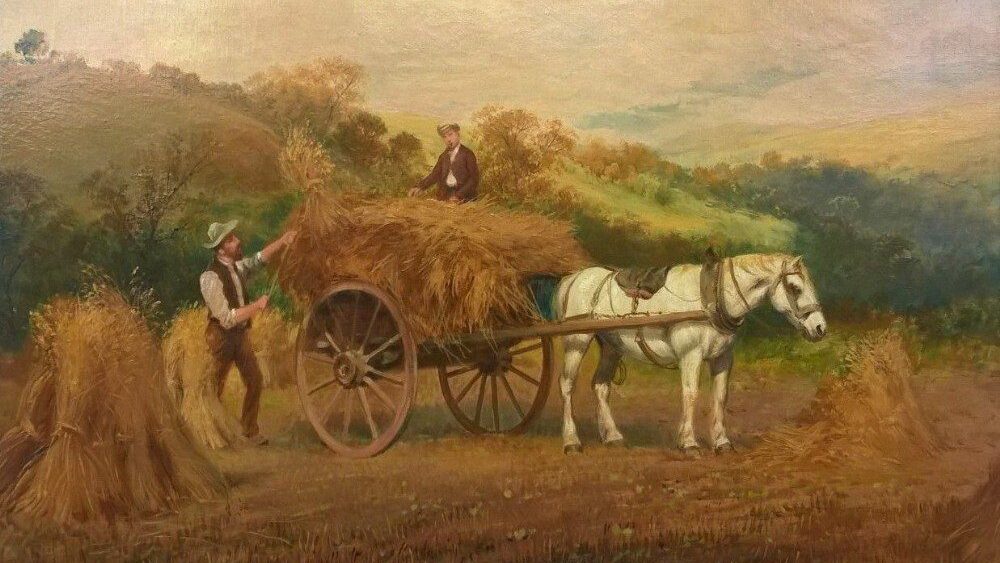

Using Plato’s analogy of the cave, the book compares and contrasts those who live exclusively in the cave with those who must venture out periodically to do the work that makes living in the cave possible. Outside of the cave, therefore, we have those who plough the fields and raise livestock while facing the vicissitudes of doing so in a physically and metaphorically hostile environment.

Meanwhile, inside the cave, the mainly urban dwellers have little appreciation of whence the food they eat comes and how it is produced. Cossetted and cosy in the cave, they use the time afforded to them not having to till the land by indulging in luxury beliefs including veganism, vegetarianism, and animal ‘rights.’ Moreover, they project those views onto the countryside, they protest violently, and they lobby politicians. Thus, the laws which govern the countryside are almost exclusively generated and imposed from the urban environment. Many of those laws, as this book shows, are damaging to the countryside and the farmers who look after it.

The environment is hostile to the extent that the average age of farmers is nearly 60, almost half of whom have mental health problems and several of whom take their own lives each month. Younger countryside dwellers—potential farmers—look at the long hours (often in inclement weather), the hostility shown to farmers from those they feed, and the effect it has on their elders, and consequently decide that this is not the life for them.

The battle lines are drawn between those in the cave and those outside over familiar issues. The urbanites look on what takes place in the countryside with distaste. Such things as rearing livestock for slaughter and hunting foxes, badgers, and corvids are trigger issues for the vegans, vegetarians, and the misinformed. The folly of these urbanites is little but misplaced sentiment. But that sentiment leads to the philosophical folly of ascribing to animals rights which are akin to human rights.

Of course, ascribing such rights is inevitably skewed towards the elegant, the cuddly, and the cute. Foxes seem to have a special place in the animal rights movement, as do any of the higher apes, whose behaviour appears to parallel our own. Remarkably, such notions of rights are easily abandoned when they have a rat infestation, or when the urban fox kills their pet cat.

Animals cannot have rights: it is a ludicrous concept. It is all very well if, in the name of such rights, an individual decides not to hunt, kill, or eat animals. But there it stops, provided they don’t expect others to follow their example. Out in the real world, animals have not rights but instincts: the instinct that they must flee from a predator or, when they are hungry, that they must chase down prey. Dogs kill foxes, foxes kill rabbits, and rabbits eat grass. At every stage of that process, something is killed, including grass.

The very idea that any of these animals feel joy or fear at their prospect is fatuous. Wightman and Nash give the perfect example of the apparent panic that is induced in herd of antelopes when a lion appears out of the long grass—only to subside when an animal is brought down and being torn to shreds. The antelope then continue to munch grass as if nothing had happened, in full sight of their former associate. Likewise, the lions, once sated, simply lie down and sleep; they don’t go chasing after more antelope for fun.

Unfortunately, within the cave, the dwellers are mesmerised by anthropomorphised documentaries from the animal kingdom voiced over by the avuncular but manipulative David Attenborough, and by BBC programmes such as Country File, in which wildlife is portrayed as struggling to survive against mankind and its most evil representatives, the farming community. Resident rural heartthrob and litigious patron saint of the animal rights brigade, Chris Packham, serves up a seasonal diet of drivel that is lapped up in the cave.

Apart from very few areas of wilderness in the UK, the visible countryside, the one that people mostly gawp at from the comfort of their cars as they drive between towns, is almost entirely managed by farmers. Only ‘almost,’ because the farmers are increasingly forbidden to touch some areas due to the oxymoronic concept of ‘rewilding,’ a contradiction in terms as it cannot ever really be ‘wild’ if once it was farmed. ‘Rewilded’ is, surely, simply another term for ‘neglected.’

Farmers manage the environment for their own good, for our good, and for the good of the creatures that live there. There are few finer sights from the train in East Yorkshire than some roe deer protruding from a field of long grass. But those roe deer, and the other deer that live mainly hidden in our fields, would not survive if they were not controlled by the guns of the British Deer Society. These are trained marksmen (and women) who know how to stalk deer and which ones to cull, instantly and painlessly. The ones who escape culling may live a few more years ultimately to succumb to ageing and illness, unable to keep up with the others until they die slowly and painfully at the jaws of a predator. Wightman and Nash repeatedly illustrate the point that nature is nasty and brutish, and life is often short but never sweet.

Packhamites and other deluded souls advocate letting nature take its course—which, in the case of our deer, would soon lead to overgrazing and starvation, the destruction of crops by hungry deer, and a reduction in farmers’ incomes. In the cave, it would mean fewer vegetables on the shelves of Waitrose.

It is impossible to include in this review all the issues covered in Dear Townie, which include objections to cool burning and reintroduction of dangerous species such as wolves. Suffice to say that they are given short shrift by the authors, accompanied always by cogent arguments against whichever stupidity those in the cave would inflict on those who must live outside of it.

I must take issue with one point in the book which occurs where Wightman and Nash explain that animals are not superior or inferior to one another, merely different due to their inherent characteristics and place in the hierarchy of predators. They say here that we humans are not superior either and that, as the apex predator, we are also merely different. I refer them to Genesis 1: 26-28.

It is hard to know what effect a book such as Dear Townie can have on its intended audience. That audience has largely been brainwashed by the social (and animal) justice warriors and is now too contaminated by critical theory to hold open minds. However, for those of us who appreciate and support the countryside and its true custodians, this book provides an arsenal of arguments and counterarguments. I thoroughly recommend it.