No products in the cart.

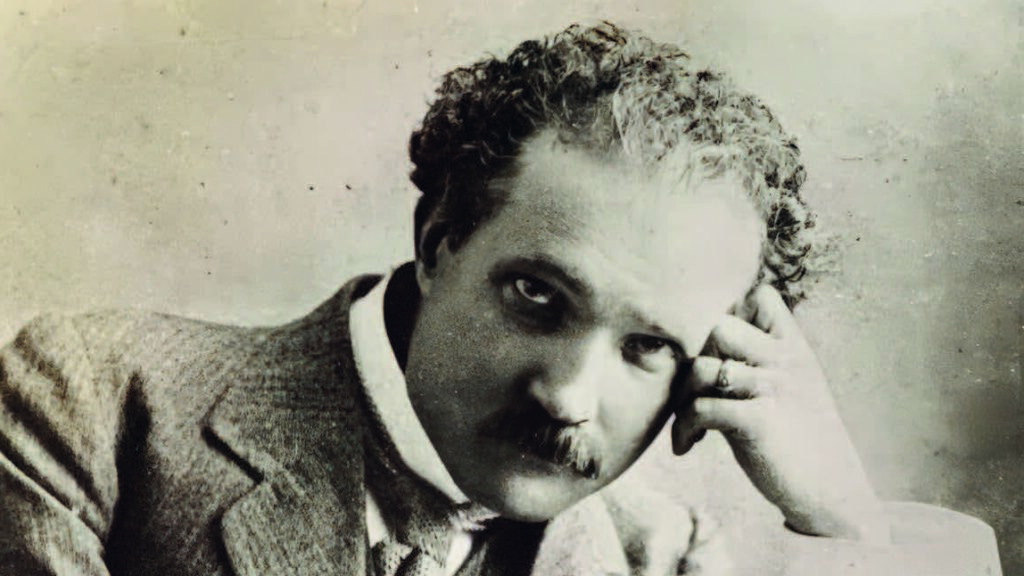

Early 20th century photograph of a young Cornelis Jakob Langenhoven writing at a desk. Photograph courtesy of the Brümmer Archive.

“In this and every generation [of Afrikaners], there is but one daily task: to keep both our

heritages—Europe and Africa—close and warm to our hearts; to be in Africa knowing

that we are from the old West; to be Western without disregarding a single influence

on us from Africa.” — N.P. van Wyk Louw

Afrikaners have a complex identity. Our predominantly Western European forefathers arrived at the southern tip of Africa, mainly from the Netherlands, France, and Germany. However, most Afrikaners, upon visiting the nations of their ancestors, say they do not feel naturally at home there. Our home is the wide-open spaces of the Highveld; the mysterious peaks and misty valleys of the Drakensberg mountains; the greens, blues, and yellows of the Boland; the red, otherworldly sunsets of the Bushveld; the dense forests of the Lowveld; the endless horizons of the Free State; the stunning wildflowers of Namaqualand, and the vast starry expanse of the Karoo night.

In the 1990s, the Harvard political scientist Samuel Huntington predicted that the post-Cold War world would be defined by the question “Who are we?” It would be naive for Afrikaners to believe that we could somehow dodge this critical question. Our culture and language, which were both formed in southern Africa over centuries and through many generations, were not built from scratch. It is here—at this convergence of two worlds—where the complex question of the relationship between Afrikaner culture’s Western and African identities becomes most pronounced.

Culture and place are two distinct, profoundly important influences on one’s identity. Afrikaners are undoubtedly ‘African’ in the sense that as a people we originated in, were shaped by, and are fully at home in the place that is Africa. Afrikaners went so far as to name ourselves after the continent, which is our only home. Even our Afrikaans language, which is an integral and vital component of our culture, is also named after Africa. In this sense, we have uprooted ourselves from Europe, the place which our ancestors of nearly 400 years ago called home.

Simultaneously, however, we are in many ways still ‘Western’ in the sense that large parts of our culture reflect the core characteristics of the wider Western civilisation. Despite its name, ‘The West’ is not a place. That is why countries like Australia and New Zealand are comfortably considered ‘Western’ despite being geographically located in the east. Early last century, the Afrikaner poet and philosopher N.P. van Wyk Louw cautioned that just as it would be wrong to disregard the influence of Africa on Afrikaner culture, it would be equally misguided—even dishonest—to deny the Western foundation on which it is built.

Despite how often the idea of ‘Western civilization’ is invoked, it is actually a rather complicated reality. To understand what it is, the work of Samuel Huntington is illuminating. He argued that global politics, conflict, and cooperation are best explained and understood through the lens of different civilisations. This use of ‘civilisations’ in its plural form differs markedly from its historical use in its singular form. To talk of different civilisations does not imply a distinction between the ‘civilised’ and the ‘uncivilised.’ In Huntington’s understanding, a civilisation entails the broadest cultural grouping, which is defined by multiple elements, including language, religion, history, customs, institutions, and subcultures or peoples. Concisely put, Huntington defines a civilisation as “a culture writ large.”

Huntington identifies Western Christianity— Catholicism and Protestantism—as the single most important characteristic of Western civilisation. After that comes language, specifically the broad categories of Romance and Germanic. Third is the classical foundations, which include Greek philosophy and rationalism, Roman law and Latin. Institutionally and philosophically, Huntington identifies the following (not exhaustive) list of core elements of Western civilisation: separation of spiritual and temporal authority, centrality of the rule of law, social pluralism and civil society, representative bodies, and individualism. Huntington emphasises that, although almost none of these factors are individually unique to the West, the combination of them is. Put differently, just as the individual ingredients of a cake are present in other recipes, their unique combination produces a specific kind of cake.

Each person’s identity is hierarchical. I am, for example, a Christian, Afrikaner, Afrikaans speaker, African, Western, South African, Pretorian, ex-Bolander, a supporter of the Western Province rugby team, and more. None of these identities negates any of the others, but they do form a hierarchy. The higher up in the hierarchy an identity is positioned, the more difficult—even traumatic—it would be for someone to lose it or to give it up. There are many voices today who demand that different peoples should only have one identity. This zero-sum sentiment was demonstrated by the former president of Mozambique, Samora Machel, when he proclaimed, “For the nation to live, the tribe must die.”

South Africa is, however, a collection of a vast multiplicity of cultures, religions, and languages. The country’s history is filled with cautionary tales of what happens when a central power attempts to standardise different cultures or tries to coerce different peoples into subordinating their languages or cultures to a single new identity. A hard reality stubbornly remains: for Afrikaners, being free to proudly be Afrikaners is a prerequisite for us to be comfortably South African. This applies to every other culture in South Africa as well—whether Zulus, Tswanas, Xhosas, Vendas, and so on. Otherwise, the South African identity feels like a domineering, exclusionary project—a jealous god.

The nuance of Afrikaner identity is demonstrated by the dual nature of our language. Our language of Afrikaans is indigenous to southern Africa. Anyone who disputes that fact should be challenged to answer this simple question: if Afrikaans is not indigenous to South Africa, then to which country is it indigenous? Despite having incorporated some inextricable influences from Africa and even Asia, Afrikaans remains part of the Germanic language family tree. Its foundational building blocks remain Dutch, which is a Western language. Afrikaans’ intimate intertwining with Afrikaner identity was beautifully expressed by the poet C.J. Langenhoven:

[Afrikaans] is the language of the farm and the home, breathing the spirit of the inexorable expanse of the sunburnt veld, charged with the memories of primitive appliances and crude self-help … It is the medium of social intercourse, the channel of expression for the deepest and tenderest feelings of the [Afrikaners]. It is interwoven with the fibre of their national character, the language they have learnt at their mother’s knee, the language of the last farewells of their dying lips.

As part of the Afrikaner culture, the Afrikaans language similarly occupies this intersection between Africa as its birthplace and home, and the West as its foundational influence. Louw observed that “Afrikaans is the language that connects Western Europe and Africa. It forms a bridge between the great bright West and magical Africa and that which can arise from their union—this is perhaps what lies ahead for Afrikaans to be discovered.”

The emphasis Afrikaners have placed on our undeniable African identity in recent years is completely justified and understandable within the context of opportunistic commentators, academics, and politicians desperately attempting to smear us as an unwelcome, invasive, alien culture that is not indigenous to or is not at home in Africa. Nowhere is this anti-Afrikaner bigotry more on display than the intellectually bankrupt political mantra of ‘Go back to Europe!’ However, as Louw wrote: “[Afrikaners] are not a small colonial group of officials and traders like the whites in the British and Dutch East Indies, but a rooted people, with no other home.” Since Afrikaners are not a colonial satellite of a larger European empire, we cannot simply be called or ordered ‘home’ by a colonial headquarters in London, Amsterdam, or Lisbon, nor can we flee ‘home.’

Afrikaners are simultaneously a Western people rooted in Africa and an African culture with Western roots. This is a deeply complex and nuanced identity-territory to occupy. However, to pretend otherwise and embrace only half of this combination—because it would be politically or socially expedient in the current climate—would be a betrayal of who we are. Louw believed that the Afrikaner culture, and the Afrikaans language’s unique bridging of two very different worlds, was a phenomenon that should be celebrated rather than stigmatised or vilified. The nature of our identity positions Afrikaners in such a way that we could potentially play a valuable role in future relations between the West and Africa.

The fact that Afrikaner culture is this unique nexus between the West and Africa is why Louw urged Afrikaners to cherish and protect the dual nature of their cultural heritage. If Afrikaners have no future in Africa, then our culture does not have any future at all. This is because within a few generations outside of Africa, we forget the African facet of the dual heritage described by Louw. However, a similar existential threat and identity crisis await us should we stay in Africa but neglect or reject our Western roots. It is precisely the preservation of this combination of two heritages which has made Afrikaners who we are. The future of the Afrikaner will therefore be dependent on whether we are able to successfully preserve this duality. The nature of Afrikaner identity is much like the colour green’s relation to the colours of yellow and blue.

Afrikaners have no other choice but to continue to keep both the African and the Western influences on our culture close to our hearts. The world of politics, propaganda, and rhetoric is inherently hostile to complexity and nuance. But by refusing to yield to these forces, it is possible naturally to align with those who prefer a complex truth over a simplistic lie. Louw lamented this frustrating fact of human nature in his own time: “I often have to ask myself with astoundment: why do people love a one-sided lie so much more than a truth with many sides? Lack of intelligence? A laziness that is satisfied with only a fragment of truth?”

Therefore, when it comes to the complex matters of identity, in a time deeply defined by such fundamental questions, let us argue, debate, and even vehemently disagree—but let us always remain principled and truthful. For, as the old saying goes, a half-truth is nothing more than a whole lie.

This essay appears in the Winter 2024 issue of The European Conservative, Number 33:34-36.