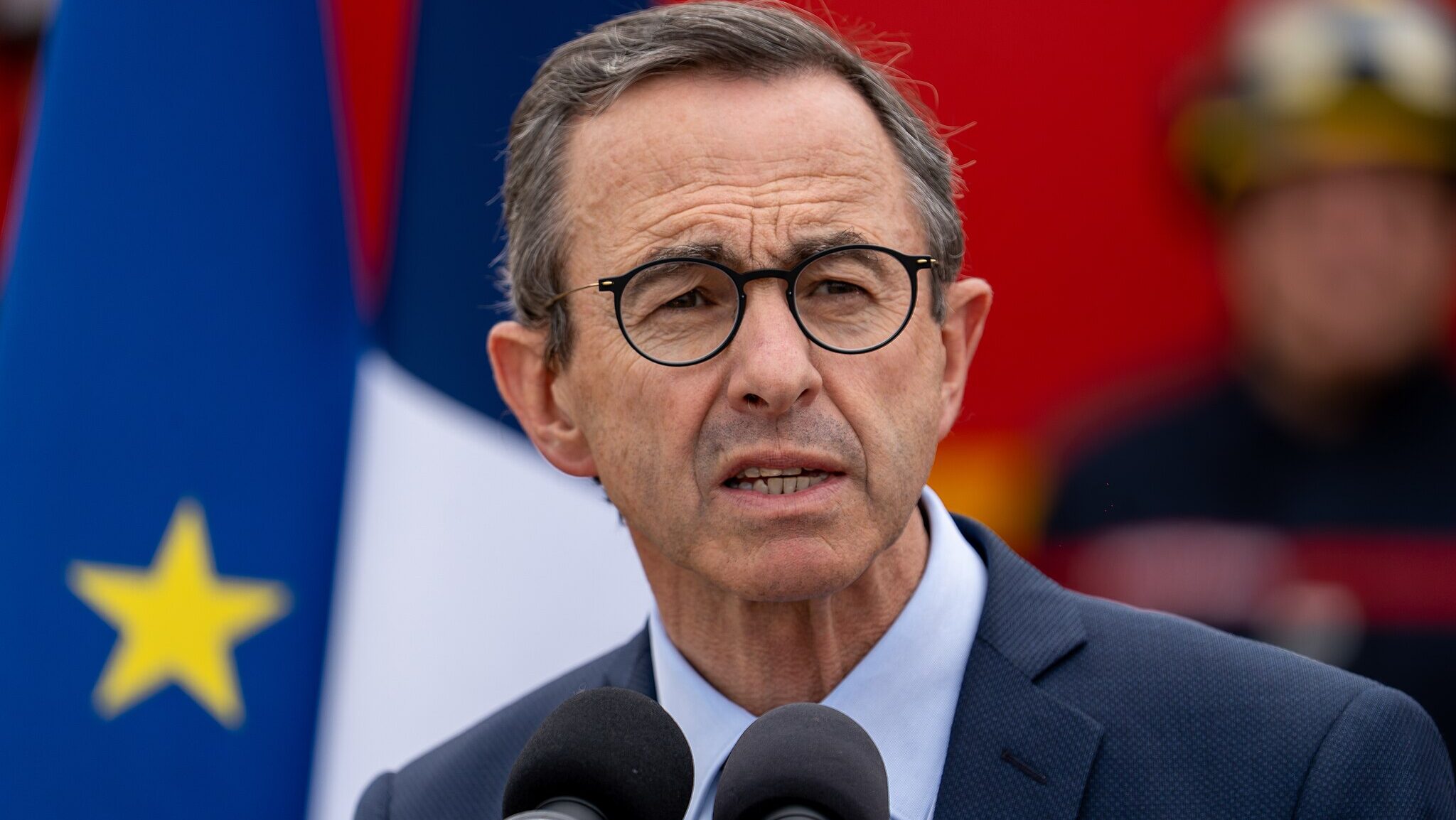

Bruno Retailleau

Anthonymontardyfr, CC BY 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Since his election as leader of Les Républicains, France’s main centre-right party the clock is ticking for Bruno Retailleau if he wants to establish himself as the ‘saviour of the Right’ and hope to win the 2027 presidential election

Part of the conservative right is already presenting him as a providential figure: it is a very French tendency to see in every politician who begins to make a name for himself in the public arena the potential Messiah who will pull the country out of the slump it has been in for thirty to forty years—since the end, in fact, of the term of office of Georges Pompidou, heir to Gaullism, in 1974.

Is Bruno Retailleau cut out for the role? He began his career in western France alongside the sovereigntist Philippe de Villiers, from whom he eventually distanced himself. The political background of the Vendée native and founder of the Puy du Fou theme park was too marginal for his ambitions. He therefore joined the Union for a Popular Movement, now known as Les Républicains, the main centre-right party in France. He then made his career thanks to the support of Nicolas Sarkozy’s prime minister, François Fillon. The latter’s failure in the 2017 presidential election, undermined by a legal scandal fuelled behind the scenes by the Left and Emmanuel Macron, could have ended Retailleau’s career, but he managed to remain in the political landscape thanks to his strategic position as leader of the centre-right parliamentary group in the Senate.

In 2022, he was tempted for the first time to run for the presidency of Les Républicains but was defeated in the second round by Éric Ciotti. In 2024, he joined Michel Barnier’s government, formed after the dissolution of the National Assembly in the summer of 2024, as Minister of the Interior.

Since his arrival at ‘Place Beauvau,’ as the seat of his ministry is colloquially known, he has devoted considerable energy to establishing himself as a proponent of a return to order and border control. A few days ago, he led a major media operation across France to showcase his ‘zero tolerance’ policy towards illegal immigration, carrying out widespread identity checks in train stations with an army of 4,000 police officers at his side.

But his harsh rhetoric—he goes so far as to claim, contrary to decades of political correctness, that immigration is not ‘an opportunity’ for France—is struggling to translate into concrete results. His colleagues are working to oppose his reform plans, such as on the thorny issue of state medical aid for immigrants. Above all, his political position remains problematic: he advocates a tough border policy and criticises euthanasia, but remains in a government dominated by centrists, where he has little influence. He, who once explained that the Right had no business “diluting itself in Macronism” is now very wary of moving closer to the Rassemblement National (National Rally), unlike Ciotti, who has crossed the divide and is now the main ally of Marine Le Pen and Jordan Bardella. He wants right-wing policies but is allowing Macronism to continue by lending it a helping hand.

His gamble is risky: on its own, the Republican right is not in a position to win, in any configuration. Even if Retailleau enjoys excellent popularity ratings, he cannot hope to win more than 10–15% of the vote in the presidential elections, which puts the second round of voting out of his reach. The stakes are political, but also sociological. Retailleau’s electorate is bourgeois, not working class. It is difficult to reconcile these two sides. For now, Retailleau has the merit of voicing truths that until recently were still taboo or reserved for the ‘evil camp’. The Left is not fooled, portraying him as the new man to beat. He still has two years to convince people that he can be a genuine solution.