In 1979, the philosopher and professor Philip Hallie published a slim volume with the bulky title Lest Innocent Blood Be Shed: The Story Of The Village Of Le Chambon And How Goodness Happened There. It told the story of the residents of Le Chambon-sur-Lignon and the Vivarais Plateau, nestled in the craggy hills of south-central France. Between 1940 and 1945, an estimated 5,000 Jews found refuge there while the Holocaust raged across Europe; the village was an island of courage amid the cruel collaborations of Vichy France. For Hallie, the story became something of an obsession.

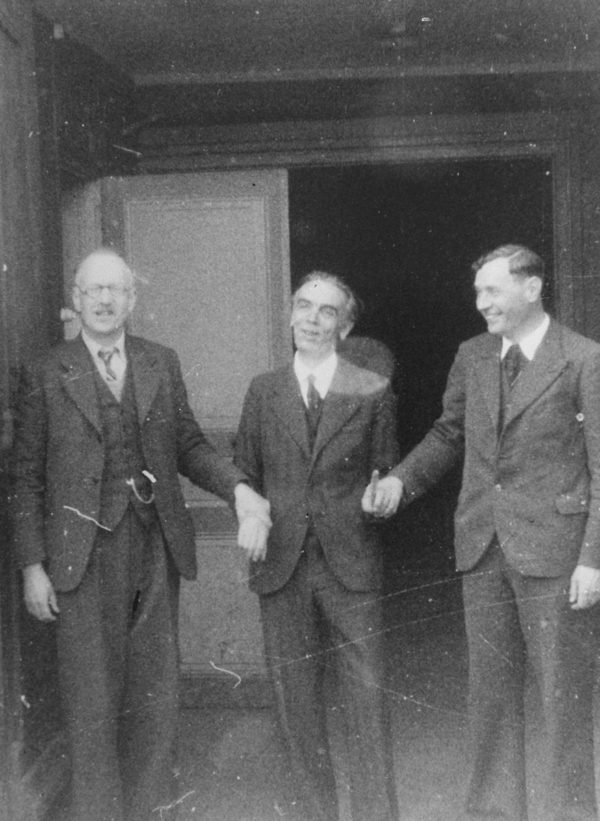

The residents of the villages of the Vivarais Plateau had been shaped by the collective memory of their own martyrdoms as a Huguenot minority, when massacres were common and survivors fled into the mountains for safety. The rescue effort during World War II was led in part by Pastor André Trocmé of the Reformed Church of France, along with his wife Magda and Assistant Pastor Edouard Theis. Fired by a fierce independence and suspicion of authority, many Protestants on the Plateau viewed the Vichy regime with contempt. When one Vichy official showed up and gave a speech ending with the cry “Long live Marshal Pétain!” a deafening silence followed. Then, one man bellowed his response: “Long live Jesus Christ!”

In the years following the publication of Lest Innocent Blood Be Shed, Hallie took to the lecture circuit to tell the story and promote the book. One night in Minneapolis, he gave a speech for the United Jewish Appeal, and a woman stood up to ask him a question. “She was a powerful woman wearing a sheath dress that made her look like a slender cannon, taut, full of explosive power,” Hallie recalled. She asked him to specify where, exactly, Le Chambon was. When he told her, her answer left the audience dumbstruck. That village, she told him, “saved the lives of all three of my children.”

She then walked to the front of the room. All eyes were on her, and nobody said a word. She faced the audience.

“The Holocaust was storm, lightning, thunder, wind, rain, yes. And Le Chambon was the rainbow.”

***

A decade after Hallie’s book was published, a documentary telling the story of Le Chambon from another perspective was released. For filmmaker Pierre Sauvage, the story was not simply another chapter in the annals of the Righteous Among Nations. Sauvage discovered as a teenager that he was born on the Vivarais Plateau on March 25, 1944; when he was 18, his parents told him that he was Jewish. In a world where Jews were being hunted and murdered with breathtaking efficiency, Sauvage was born, he would later say, “in a place uniquely committed to my survival.” The discovery changed his life.

The award-winning Weapons of the Spirit is a powerful piece of storytelling that bears much resemblance to the Shoah films of Claude Lanzmann, but without the sensation of being slowly crushed by the horrors of the Holocaust. Sauvage’s film is an homage to the Huguenots and the other rescuers of this extraordinary community, whose commitment to the persecuted was forged in the fires of their own centuries-long struggle for survival against Catholic authorities determined to snuff them out.

Huguenot history describes that struggle as The Desert. During vicious persecutions stretching from the sixteenth to the eighteenth centuries, the Huguenots of the plateau frequently offer refuge to other Protestant refugees as well.

“Everything they did,” Sauvage says in the film, “was an echo of their forefathers’ faith. The village was prepared by its Huguenot past.” This conclusion was at first difficult for him to accept when he began to explore the story in the 1980s.

“I come from a very anti-religious background, and here I was making this documentary about religious people,” he told me.

I found all of my prejudices falling by the wayside. I honestly thought there was something dimwitted about people who are religious. They’re not evolved, like I am. And yet here were these people who were among the smartest people I’ve come to know in my life. I slowly let that in. The process of making and editing the film was very difficult, because for a long time, I didn’t understand what these people were saying to me.

Who were these people who lived on the plateau that became “the most concentrated area of rescue to take place for that length of time anywhere in Occupied Europe?” “These were hill people, used to centuries of perseverance as a religious minority,” said Sauvage. “The village was a barnacle clinging to the rocks. Unhospitable. Naturally rocky soil. Very forbidding, cold during the winter. A lot of snow. But the people there clung to God and to each other.”

The old stone church of Le Chambon had a simple phrase carved above the doorway: “Love One Another.”

***

Le Chambon’s pastor André Trocmé was a committed advocate of nonviolent resistance who preached frequently against antisemitism in open defiance of the authorities. Every order that contravened the Gospel, he told his congregation, needed to be disobeyed without fear and without hate. In one sermon, he publicly condemned the mass roundup of Jews in Paris at the Vélodrome d’Hiver, stating that “the Christian Church must kneel down and ask God to forgive its present failings and cowardice.” Trocmé believed passionately that resistance could be accomplished without violence: “It is the duty of Christians to resist the violence brought to bear on their consciences through the weapons of the Spirit.”

“Under the spiritual leadership of André Trocmé,” Sauvage observed in Weapons of the Spirit, “Le Chambon became the nerve center and symbol of the spiritual resistance.” Along with fellow pastor Edouard Theis, pastors from nearby churches, and a collection of other rescuers that included American Quakers, the Swiss Red Cross, Evangelicals, several Catholics, and the Jews themselves, an organized rescue effort—unparalleled in Occupied Europe—began in 1940.

It started by sending relief supplies to Jews jailed in internment camps in southern France. This project was facilitated by the American Friends Service Committee based in Marseilles, as well as La Cimade, L’Ose, and others. Then the American Quaker Burns Chalmers told Trocmé that if the release of some Jewish internees could be accomplished, it would be necessary to find a place for them to hide. Without hesitating, Trocmé told him that Le Chambon would help.

Chalmers began to secure the release of Jewish prisoners, primarily children. They were taken to Le Chambon, where rescue workers placed them in homes and on farms in the scattered villages across the plateau and beyond. Working with the American Congregationalists, an assortment of organizations, and even the Swedish government, rescuers supplied Jewish refugees with food, clothing, and false IDs. Schools and youth organizations welcomed Jewish children and helped them integrate into the community.

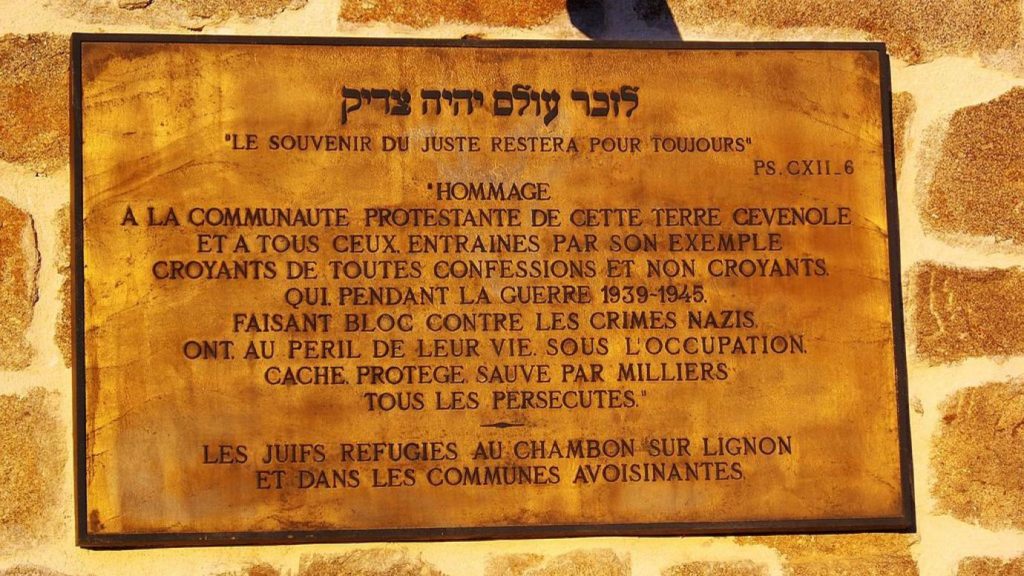

PHOTO: LIEU DE MÉMOIRE DU CHAMBON

When the Resistance warned that Nazi or Vichy raids were coming, rescuers moved Jews further into the countryside and even smuggled some across the Swiss border.

Word about the safe haven soon spread, and Jewish refugees, anti-Nazi Germans, and other dissidents made their way to Le Chambon. All were welcomed. The sheer solidarity of the hill people made the Vichy authorities cautious, and some police officers even tipped off the villagers before launching raid. Many officials looked the other way. The villagers refused outright the demands by authorities for lists of Jews living in the area. Andre Trocmé’s response: “We don’t know what a Jew is. We only know human beings.”

“Nobody asked who was Jewish and who was not,” recalled former child refugee Elizabeth Koenig-Kaufman years later. “Nobody asked where you were from. Nobody asked who your father was or if you could pay. They just accepted each of us, taking us in with warmth, sheltering children, often without their parents—children who cried in the night from nightmares.”

Rescuer Madame Dreyfus recalled that, far from recoiling from the risks involved in helping Jews, the villagers of Le Chambon were more likely to help if the refugees were Jewish. In one instance, she was having trouble placing two teenagers, and an elderly couple at first resisted her request. Teenagers were very difficult, and they ate a lot. Desperate, Dreyfus finally told them the truth: These children are Jewish. They’re being hunted. The transformation was immediate. Why didn’t you say so earlier? the old couple responded, and immediately took the two teens in.

To the Huguenots of Le Chambon, the Jews were the Chosen People. As one elderly woman told Sauvage: “We did it because they were the people of God.” It was essential, she added, that people did not act like the priest in the parable of the Good Samaritan. One of the code names for the Jewish refugees was “testaments,” a reference to the fact that they were the people of the Old Testament. During one church meeting on the Plateau, an evangelical pastor announced to his congregation that “three testaments had arrived.” An old man immediately stood up. “I’ll take them,” he said, and brought the refugees to his farm.

“There was something different about Le Chambon,” Sauvage told me.

They really underscore something that is true of rescuers in general. I grew up with the notion that rescuers were larger-than-life figures who almost reluctantly did what they had to because they felt compelled to do it. I’ve come to realize that that’s nonsense. Rescuers are people who act according to their inner need, and as a result, it comes naturally to them. They don’t think it’s any big deal. There are moving testimonies where the Jews talk about their rescuers not only being willing to provide shelter but being eager—experiencing it as a privilege. That is a very particular mindset.

Part of that mindset came from the land itself. “As a city guy, I had a very common prejudice that we city people have towards people in more rural areas,” Sauvage reflected.

I’ve come to believe that people who live close to the elements, above all else, have a sense of what is natural more than we do in the cities. It’s a very unnatural environment, a big city. But they depend on the elements, they get used to them. They were also used to duress, used to hardship. That is definitely a big part of the story. Peasants end up getting a bum rap when in fact you were more likely to be sheltered during the Holocaust by a farmer or a peasant than you were by a university professor.

A personal example stood out. “I suppose I’m particularly attached to the old couple who helped my parents. Their daughter took care of me. They were the first people I interviewed because I knew they couldn’t say no because we did have this relationship.” From here, he said, the word spread. “People became more and more willing to be interviewed by me. I pressed them on why they did what they did: Did you know it was becoming dangerous? They said yes, of course. But you did it anyway? And the woman says: Yes, we were used to it. And she shrugs.”

This, Sauvage told me, was the essence of it all. “I love that expression: We were used to it. Because good conduct is also something that one has to get used to. Judaism often places a great stress on what you do, because as you do it, you’ll get used to doing it, and you’ll do it more and more. You don’t have to think it through so much, you just do it.” But this sense of responsibility did not weigh heavily on them; rather, it seemed freeing. “The good people that I have known are generally happy,” Sauvage said. “I sort of had the notion that good people might be plowing under the weight of being good. I came to realize that good people are happy, they live fulfilled long lives, and they often die surrounded by their loved ones, at a ripe old age. The good die old.”

Not all the good, of course. On June 29, 1943, Nazi police raided a secondary school, La Maison des Roches, and arrested 18 students. Five of them were identified as Jews and shipped to Auschwitz. Their teacher, Andre Trocmé’s cousin Daniel, was shipped to Majdanek. All six were murdered. Le Chambon’s doctor Roger Le Forestier, who had been a key figure in obtaining false identification papers for Jewish refugees, was shot alongside over 100 other resistance fighters on August 20, 1944, in Montluc prison on the orders of the sadistic Gestapo chief Klaus Barbie. Le Forestier was the doctor who had delivered Pierre Sauvage.

PHOTO: UNITED STATES HOLOCAUST MEMORIAL MUSEUM, COURTESY OF JACQUELINE GREGORY

The pastors Trocmé and Theis were also arrested on February 13, 1943 but were freed after 28 days and promptly carried on their work. Later that year, after being warned that they were soon to be rearrested, they went back into hiding. Magda Trocmé continued to contribute to the rescue operation. “We did not have an ordinary house, we had a Grand Central Station house,” her daughter Nelly Trocmé told me. “Refugees were always in and out.” On September 2, 1944, the Vivarais Plateau was liberated by the Free French 4th Armored Division and the maquis (Nelly remembers her father getting along well with the head of the maquis despite their tactical differences, and some friends of hers from school joined).

During the four years of Occupation, nearly 75,000 French Jews died in the death camps. The gruesome number masks another number: in an extraordinary, ongoing act of resistance, the French people hid–and saved–75% of the Jews in France.

***

The story of what happened at Le Chambon and the surrounding areas became a source of unusual controversy several years ago, when popular historian Caroline Moorehead released Village of Secrets: Defying the Nazis in Vichy France. Her book, Pierre Sauvage noted in a scathing review, attempts to downplay the importance of religious convictions in motivating the rescuers to undertake their monumental task:

There may well have been a few atheists and agnostics too on what was then known as the Protestant mountain, and it is possible that some of them may have joined in the rescue effort—though they have not been identified as yet by Moorehead or anybody else. But to equate Catholic, atheist, and agnostic efforts with the role of Pastor André Trocmé and the role of the other Protestant pastors of the area and the role of the French Protestant population as a whole is to deny what virtually every single Jew who went through there then would tell you: That this was fundamentally a Huguenot undertaking, centered in Le Chambon-sur-Lignon, and deriving much of its initial momentum and energy from the pastors of Le Chambon, André Trocmé and Édouard Theis—and their historic call to resist through the ‘weapons of the spirit.’

When I asked Sauvage about Moorehead’s motives, he observed that many academics have trouble understanding religious motivations. “It takes an effort to let in something different from you. It took me several years to edit this film because I couldn’t allow myself to do that. It certainly changed me. Where people often get it wrong is that they bring their particular bias to the story. There are people who write books who are attracted to the story, but they don’t want to acknowledge the religious dimension of the story. That to me is ridiculous. That was part and parcel what made Le Chambon.”

Simply put: Without the Protestants, the story of Le Chambon would have unfolded much differently.

—The Jews who found refuge in Le-Chambon-Sur-Lignon and neighboring communities

***

Much of Sauvage’s career has been spent telling the story of Le Chambon and other Holocaust rescuers, including through the Chambon Foundation, which seeks to “explore and communicate the necessary and challenging lessons of hope intertwined with the Holocaust’s unavoidable lessons of despair.” Weapons of the Spirit has been widely used as a documentary teaching tool on the Holocaust. Sauvage’s efforts resulted in French President Jacques Chirac making a major address at Le Chambon in 2004, and Nicolas Sarkozy called the film “deeply moving.” In 2013, a museum commemorating the rescue was finally established in there, ensuring that the “conspiracy of goodness” would be remembered even as those who lived through those days of darkness and night take their leave.

It is the ordinary nature of their goodness that makes the story of Le Chambon such a miracle. It was weathered men and women with brittle hands, shiny with callouses from backbreaking work, hard as oak and often gnarled with age, who did these things. “Why,” Sauvage asks towards the end of the film, “when the world cared so little, did a few care so much?”

And the answer to his question came from one old woman, her grey hair in a neat bun, giving a slight shrug. “It was not a sentimental faith,” she said. “It was nothing extraordinary. It was a solid faith that was put to the test and not found wanting.” That simple faith, for thousands of people, would become the shield that granted them safety in a world gone mad.