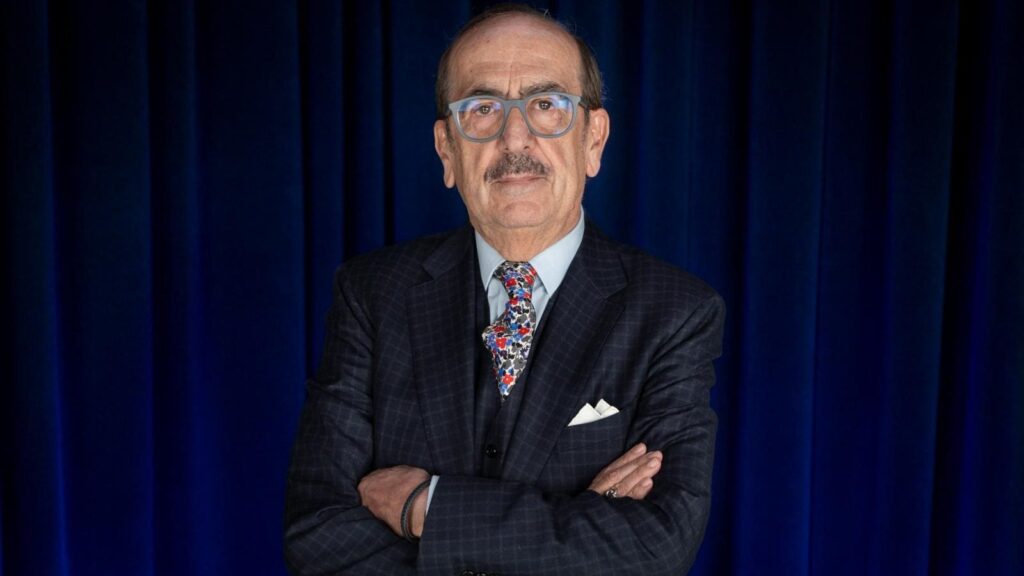

In the fall of 2020, Professor Ted McAllister began to conceive of a postgraduate course in the Pepperdine School of Public Policy called Manliness: Courage in a Disordered Age. The course was created in large part as a bulwark against two forces the conservative intellectual historian witnessed besieging this Christian University terraced into the hills of Malibu, CA: therapeutic culture and ‘safetyism.’ Both of these forces had particular iterations at Pepperdine; and yet both of them are examples, en miniature, of a culture of risk aversion and non-confrontationalism that permeates Western institutions.

Safetysim, as authors more eloquent than I have argued, is the prioritization of one narrow metric of health and well-being—prevention of illness—at the expense of a more robust conception of human flourishing. Therapeutic culture of the kind embraced by progressive elites, for its part, prizes self-esteem and subjectively defined well-being above “a culture oriented towards virtues,” and the search for truth, as McAllister put it in an editorial. Or, as Carl R. Trueman says in The Rise and Triumph of the Modern Self (2020):

In a world in which the therapeutic dominates … students … may well feel entitled to have educational norms conform not to traditional educational goals but rather to those that play directly to that inner sense of psychological well-being that is central to the idea of the therapeutic.

The hegemony of therapeutic culture at universities produces puppy-petting events and rooms with juice and cookies for students triggered by the victory of the wrong presidential candidate. The Pepperdine administration’s dutiful obeisance to school closures—that is, to safetyism—in place of “the university stand[ing] up against an unauthorized unit of government seeking to control us in areas where they had no jurisdiction,” was one piece of evidence of the school’s—and the West’s—effete degeneration into complacency and complicity with the un-democratic administrative-managerial state. In addition, a recent eruption of woke attacks on those who argued against the 1619 project “exposed the degree to which a substantial part of the university was more interested in (false) narratives than the hard work of empirical truth and how this ideological devotion to a narrative of oppression came with an unwillingness to engage in meaningful debate or conversation based on evidence,” according to McAllister.

“So,” Professor McAllister told me, “if the goal was to educate,” the alternative to a zero-risk leftist-agoraphobic Weltanschauung “was to teach manliness rather than safetyism, to teach spiritedness [thumos in Greek] rather than love of comfort and ease, to teach the need for risks as a part of any life worthy of living.” And thus a course was born.

The relationship between “manliness” and thumos is a complicated one. Spiritedness itself is not a gendered word in the Greek, as McAllister points out to me, while noting that both he and Harvey Mansfield, author of the controversial book Manliness (2006) borrow from the Greek concept to inform their definition of manliness. Women also possess spiritedness—Mansfield cites Margaret Thatcher as one such example. Nonetheless, McAllister proposes that there is a fundamental difference between women and men when it comes to spiritedness:

Given that men have greater measures of spiritedness in order to complete their masculine nature and, in our age, feminism and other forces are seeking to deny or undermine the role of thumos (which is a necessary condition for men to be men, even if women also have a measure of thumos), I want to stress [in this course] both the universal “nature” of humans in having this part of our soul and the much greater need for men to cultivate a healthy form of spiritedness to be properly men. [emphasis mine]

When society lacks manliness informed by thumos and molded by virtue, the result is not another esoteric academic debate. The West’s lack of manliness has at once snuck up on us over the last few decades and smacked us in the face in the age of COVID: “Fear of risk, an exaggerated love of safety or health, are pathologies that threaten the very virtues necessary for civilizational and cultural survival”—or so Professor McAllister proposes in a uniquely worded course syllabus that reads like a blend of theoretical treatise and op-ed.

Manliness is not a universal good, as Mansfield explicitly points out in his book, and yet it can ascend from nihilistic aggression to purposeful self-assertion in the service of a greater good. (Think for instance of Churchill’s life-long obsession with fame and recognition and his indispensable role in staring down Nazi aggression). As McAllister lays out the paradox nicely: “In ages of disorder, then, we confront the need for the most dangerous part of the human soul to save us, to bring a return to order.”

The danger, and the redemption, of manliness—the distinction, one might say, between rash aggression and principled self-assertion—is evident all around us. If we are to take the concept seriously as a hermeneutical tool, then we might isolate two examples in which the literary and philosophical reservoirs of thumos can be used to judge the present. Ron DeSantis and Vladimir Putin come to mind.

In the case of the former, the Florida Governor was excoriated for lifting lockdowns and mask mandates well before the science of the experts—and, some would argue, the advent of a vaccine—ultimately came to the same conclusion. Was this an example of reckless manliness, of the ego preceding the rational self? Or was it a textbook case of thumos in action—of principled assertiveness in the face of competing dangers, health and freedom? As China continues its inhumane zero-covid policy and even liberal states like California begin to sour on lockdowns and mask mandates, it seems more and more to be the case that DeSantis exhibited manliness—daring and risk-taking in the face of the imperative to follow the herd—as opposed to reckless aggression.

With troops invading Ukraine as we speak, is Putin the example of principled manliness par excellence some admire or cautiously respect? Or is he an example of what Harvey Mansfield has termed “manly nihilism”—ultimately reckless assertiveness as a testament to one’s ‘will to power,’ but devoid of any coherent moral-ethical framework or tradition?

Contemplating President Putin’s bellicose actions of late, I am more convinced of the latter, and I am reminded of Harvey Mansfield’s observations about the impact of Nietzche and Darwin on modern manliness:

Willpower manliness can appear to have an air of desperation or can be said to be desperate underneath despite an air of confidence on the surface. Some would interpret … manliness as too emphatic to be true because true manliness has more quiet in its confidence, less stridency in its assertiveness.

Whether or not Putin’s manliness is sound of mind, it is increasingly clear—as Ted McAllister’s course on public policy suggests—that the West could use more in the way of manliness, more of this ballast that once undergirded liberal societies of the Occident. As Senator Josh Hawley said in his speech on manliness last October for the National Conservatism Conference: “Assertiveness and independence are strengths when used to protect and empower others.”

“These virtues,” Hawley explains, “are the bright side of the aggression and competitiveness and independence that psychologists, no less than philosophers, have long observed in men.” While not liberal virtues, these are nonetheless needed for the very survival of the liberal polity.

After an afternoon spent sitting in as an observer in Professor McAllister’s course on manliness, I was led out to a quiet edge of campus that looked down on Malibu and the other Pepperdine Colleges below. The spot is called The Heroes Garden. “There’s no better view on campus that I know of,” McAllister says pensively. The might of the Pacific loomed below. The smell of sea air pushing into the hills filled our chests. The respite was welcomed after three hours indoors.

“One of those who stormed the cockpit of Flight 93,” Dr. McAllister tells me, “was a Pepperdine alumnus” (Thomas Burnett Jr.). Whether the irony in taking me to this particular spot was intentional on the Professor’s part or not, it wasn’t lost on me–in an age of disorder, manliness can preserve or destroy. And in the end, in moments of crisis, like it or not, we need it.