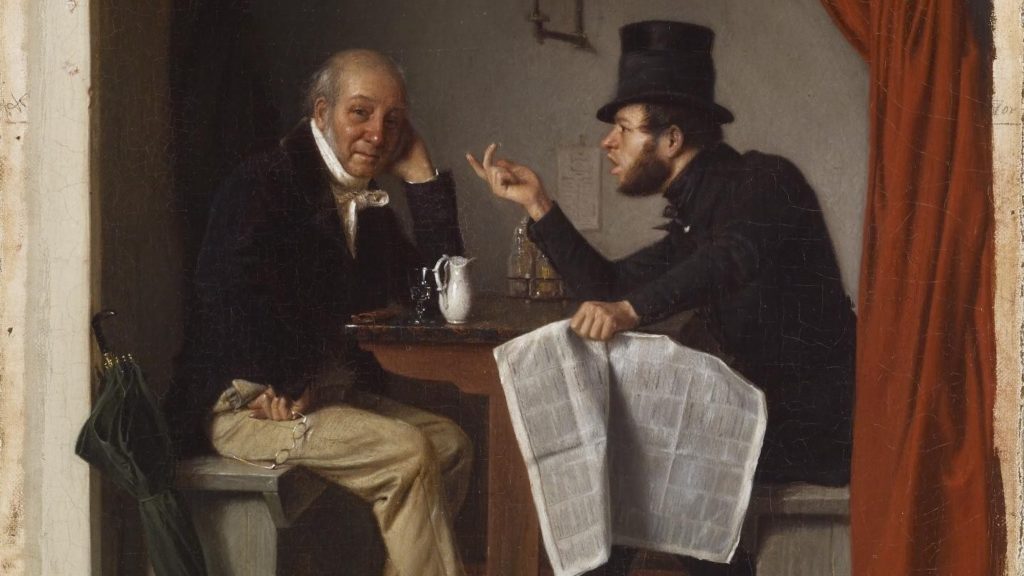

“Politics in an Oyster House” (1848), a 41.2 x 33.1 cm oil on fabric by Richard Caton Woodville (1825-1855), located in the Walters Art Museum, Baltimore.

Attempting to expound someone else’s thought is always a high-risk endeavor. But since I recently declared Dalmacio Negro Pavón the most significant political thinker in Spain in recent decades, with all due caution, I will outline what I consider to be some of the interpretive keys to Negro Pavón’s thought.

The work of Dalmacio Negro Pavón reveals that politics cannot be understood without anthropology: the various conceptions of humanity throughout history are not mere theories but paradigms that have shaped the lives of peoples and conditioned political thought.

Whether the Iraq War, the financial crisis of 2008, or the inexorable ascendancy of cultural progressivism, history does not appear to have affirmed the conservative cause over the past twenty years or more. But how are conservatives to respond? The future direction of the Republican Party, the main political vehicle of conservatism in the United States, remains contested. This battlefield or disputed ideological terrain is, in my view, divisible into two camps: the uncompromising ‘Never Trumpers’ and those who would make common cause with either the man, the movement, or both.

Ever since President Trump’s thunderous arrival on the GOP political scene, liberals of the Left and Right continue to pine for their old political ‘end of history’ stalemate: a domestic polity without any economic, regulatory (Right liberals) or lifestyle constraints (Left liberals), a basically borderless international community, and the agreed-upon globalism in which goods, capital and people can be treated as fungible items of free-market exchange. Most contemporary progressives, with their irrational unwillingness to consider Trump as anything other than a racist fascist, are obviously difficult to have constructive conversations with at the moment, but rightwing ‘Never-Trumpers’ should theoretically know better than to dismiss every aspect of Trumpism. Such figures–politicians and pundits–have buried their collective head in the sand and refused to acknowledge the reality that the Republican Party is permanently altered.

In the meantime, the most serious debates about conservatism’s future emanate from elsewhere. That is, they originate from the dissident Right–from movements that at once acknowledge conservatism’s patent failures during the Reagan and Bush years and honestly address the necessity of political realignment on the right.

The elements of the dissident Right with the most verve and scholarly heft today are, in my view, the so-called ‘Postliberals’—among them Patrick Deneen, Yoram Hazony, Sohrab Ahmari–and the perhaps lesser known, or lesser understood ‘Claremont School,’ including Charles Kesler, Robert R. Reilly, and Michael Anton. The former camp (the Postliberals) traces its roots to the ancient political thought—some by way of Edmund Burke, others vis-a-vis integralism and the writings of Thomas Aquinas. The latter camp, conversely, also sees its roots to ancient political thought (particularly Plato), but they specifically approach the ancients through the readings of Leo Strauss. For many of this ilk, Strauss’ protege, Harry Jaffa, is also a crucial guide for thinking about American politics, mainly because of his influential interpretation of the Civil War and Lincoln’s presidency as a ‘second founding’ of the nation. The Claremont Institute, perhaps the central institution for this strand of political philosophy, was founded outside Los Angeles in 1979, which gave birth to the comical moniker ‘Claremonsters.’

Both the Postliberals and the Claremonsters boast many adherents who are unapologetically populist and nationalist and, to varying degrees, pro-Trump. While both movements developed after the advent of twentieth-century American ‘fusionism’ that dominated Cold War American conservatism, each could plausibly claim a home under the fusionist tent. Fusionism, a term coined by Frank Meyer of National Review, denoted the alliance of religious and social conservatives, free-market libertarians, and anti-communist internationalists under a big tent Republican Party. It experienced its apotheosis in the Reagan presidency, where it was in effect the reigning political philosophy.

One difficulty fitting the Postliberals and the Claremonsters into American fusionism, however, is that they are two of the camps putting the most pressure on the content of the post-WWII fusionist consensus. Each camp argues (for its own reasons) that the Reaganite fusionist consensus is dead and cannot be revived. Both are highly critical of traditional fusionism’s trust in unfettered international trade and believe globalism is ultimately unfulfilling for nations and the people that inhabit them. The Postliberals (and some of the Claremonsters) also oppose the idea of a neutral public square, arguing that the attempt to create such a space, instead of protecting those of all views, has instead sidelined all those who do not parrot progressive orthodoxies.

Perhaps the greatest disagreement that remains, however, is the place the American Founding ought to have in contemporary conservatism. Were the American founders, and was the American Founding, flawed from inception, as some Postliberals claim? Or has the founding been corrupted, as the Claremonsters argue? If the latter is the case, can the founding be recovered? Or is it time to move on, as the Postliberals suggest, towards political horizons as of yet to be fully conceptualized?

A recent debate, hosted by the Abigail Adams Institute and the Intercollegiate Studies Institute (ISI) entitled “Return to the Founding to Save America?” and featuring spokesmen from each camp–Patrick Deneen (Postliberal) and Michael Anton (Claremonster)—illustrated at once the vibrancy, disagreements between, and—as I will argue—complementarity of the two most serious intellectual movements within the inchoate populist GOP.

In broad terms, Anton espoused the view that America’s founding was not inherently flawed; that study of the Constitution of 1787 and the context in which it was written is still of value to the American conservative movement; that the classical liberalism of the founders was not evolutionarily predisposed to radical individualism and materialism; and that the deleterious state of America’s current politics and culture are attributable to more recent pathologies, not a genetic defect in the thinking of the Founders, or even of enlightenment rationalist figures like John Locke or Adam Smith.

While Anton opened his remarks by expressing his agreement with many aspects of his intellectual opponent’s interpretation of the last few centuries, he worked to distinguish the cancerous elements of early modernity that have grown into contemporary progressivism from the philosophical and theological roots of the American project. Thus, he observed that “most of,” Deneen’s evidence critiquing the American founding, is more “from [enlightenment] philosophers and writers and less from the Founders themselves, who absolutely did believe in the classical-biblical view that the purpose of freedom is for human flourishing and the practice of the virtues.” He went further, offering a cautious defence of some aspects of Enlightenment philosophy, pointing out that even from the works of Locke and Smith one can extract selections emphasizing the importance of Christian morality or individual virtue classically understood. Such selections contradict the notion that the Founders’ philosophy was founded on “low but solid” ground of a rational self-interest, understood almost exclusively in materialistic or economic terms, as opposed to the loftier pursuit of the common good or justice.

In his arguments, Anton is in agreement with Charles Kesler’s book Crisis of the Two Constitutions (2021). To Kesler’s mind, serious study of the American founding since the end of WWII has in fact created a formidable phalanx against the Progressives’ idea of a ‘living constitution’ meant to constantly update itself to the times:

After World War II, an unanticipated and unsung revival of political philosophy began… questioning historicism and nihilism in the name of a broadly Socratic understanding of nature and natural right…Thanks to this intellectual rebirth, the case against Progressivism and in favor of the Constitution is stronger and deeper than it has ever been. Progressivism has never been in a fair fight, an equal fight, until now, because its political opponents had largely been educated in the same ideas, had lost touch, like Antaeus, with the ground of the Constitution in natural right…The superficiality of Progressive scholarship is now evident. They could never take the ideas of the Declaration and Constitution seriously.

In Kesler and Anton’s telling, then, a “return to the founding” has in fact yielded fruit by providing intellectual ammunition against the liberals’ administrative and deep state or rule by regulation and decree. We can think most immediately of the arguments recently evinced in the Supreme Court’s recent ruling that the supposed “right to abortion” is not in fact protected by the Constitution.

When Patrick Deneen took the podium, however, he painted a very different etiology of America’s ills and corresponding prescription for healing the nation. Reiterating points he’d made in his book Why Liberalism Failed (2018), he asked his audience a question that would sting any honestly self-assessing conservative: “Should conservatives keep doing what they’ve been doing? How is that working out for us? Just look around you. What has been conserved?”

Deneen posed his questions in a combination of lament (for what conservatives have lost) and challenge (to the status quo of Republican party orthodoxy). Deneen asserted that too often the “call to return” to America’s founding values has turned America into something “timeless and placeless,” a mere “theory” or an “abstraction,” shunting aside the particularity of American traditions, American history, and American national identity.

In his recent book, Conservatism: A Rediscovery, fellow Postliberal Yoram Hazony echoes Deneen’s assertion that American liberalism is too often a set of abstractions disembodied from the messy realities of everyday life. He also imputes this same flaw to “enlightenment rationalism” (read: liberalism) writ large. Many of enlightenment liberalism’s most prominent boosters, Hazony brilliantly points out, shared a common denominator in their family life (or lack thereof):

Hobbes, Locke, Spinoza, and Kant never had children. Descartes’s only daughter, born outside of marriage, died at the age of five. Rousseau had five children with a mistress but abandoned all of them to an orphanage in infancy. In other words, Enlightenment rationalism was the construction of men who had no real experience of family life or what it takes to make it work…It is a political theory made in the image of unmarried, childless individuals.

Enlightenment and post-Enlightenment Liberals, then, have always had a propensity to live in the airy, ethereal world of abstract theory, as Harrison Pitt recently observed in these pages. For Deneen and Hazony, then, Conservatism’s “return” must be not to classical liberalism per say but to a lived conservatism with roots in the preliberal soil of life as it is actually lived–within families, tribes (communities), parishes, and, of course, nations.

But can the lived conservatism of the Postliberals find common ground—and common political cause—with the universalist notions of natural right, justice and equality espoused by the Claremont School? On this question, I believe, hinges the fate of a new conservative fusionism updated to meet the challenges of our time.

Before I attempt to provide a provisional response to this query, it is worth reporting something that arose in the question and answer session following the debate. There, Deneen argued that American conservatism needs to envision “a less theoretical, less ideological America,” and that “we need more history, less theory … [we need to ask] What is the good? What is the common good?”

To this, Anton replied that Deneen had argued for a “less theoretical account of the founding” but that he’d also “raised fundamentally theoretical questions: What is the good? What is the common good?” “I don’t think you can answer those questions adequately,” Anton contended, “or even primarily … without thinking theoretically.” Where Deneen posited that conservatives need more memory and understanding of the past in an organic, non-ideological sense, Anton suggested the pronouncement of universal ideals are at some point ineluctable—otherwise, slavery and other barbaric practices could be explained away or even “justified” as embedded traditions to which one must defer.

The apparent dispute between Anton and Deneen over natural rights is not an insignificant disagreement, and as more distance accrues between the disastrous liberal interventionism in Iraq, Afghanistan, and elsewhere in the name supposedly ‘universal’ democratic values, this debate will without doubt intensify. However, the two men seem to be aiming at the same thing: a recovery of a healthy political and social life that values tradition and the common good. Can the movements they represent perhaps learn from one another and stand as two parts of a 21st century conservative movement positively affecting America and the world?

Perhaps instead of being mostly antagonistic schools of thought, the Postliberals and the Claremonsters can complement one another within a new victorious fusionism. Where notions of natural rights lead too often, in practice, to an abstract, ahistorical, and ultimately dry and deracinated conservative politics, the Postliberals can bring the movement back to the solid ground of lived experience—of the realities of community building in its sundry familial and interpersonal forms so desperately needed today. In turn, where postliberalism’s emphasis on tradition and religion can smack of nostalgia for the throne and altar conservatism of reactionary Europe, the Claremont school can remind the former both of the continuity between the ancients and the best of the moderns, between classical natural law and the Declaration’s Universal truths.

For Postliberals, ‘liberalism’ itself is the problem. Patrick Deneen, Yoram Hazony, and others have electrified conservative intellectual circles and captured the essence of the new Republican base by directly attacking America’s ‘liberal’ status quo. They have opened an exciting new front in the culture wars by pivoting from the old fusionist strategy of seeking ‘tolerance’ from liberal elites to advocating unapologetically for the claims to truth of classical and Judeo-Christian views of man (and sometimes even Christian faith) in the public square.

At the same time, however, while Deneen and others insist on the irrelevance of all that is liberal, the Claremonster continue to see value in the founding documents of classical (American) liberalism: the Declaration of Independence, the American Constitution, the Federalist Papers, letters exchanged amongst the Founders, and other primary sources. Postliberals and Claremonsters agree in large measure on what went wrong, but they disagree over why it went wrong. Their answers to the question of why America’s unique Christian and nationalist republic went off the rails—by straying from or precisely by seeing through the founding values to their logical conclusion—will continue to differ. Perhaps the best outcome for American Conservatism would be that each school continue to challenge and compete with one another under the same fusionist tend so that the nascent nationalist-populist American right never settles into the stolid consensus of a conservatism that, for the past twenty years, has, to paraphrase Professor Deneen, conserved little.