My article last week about the proposed tax cuts in Sweden caused a bit of a stir, given that I was critical of how the center-right government has designed those cuts. After all, aren’t we conservatives supposed to always appreciate lower taxes—especially when they are spearheaded by conservative governments?

The answer, alas, is no. I am not a fan of the cheerleader approach to politics: those who are will applaud whatever a conservative government does for the sake of team spirit. I happen to believe that conservative governments will do best when promoting conservatism using conservative policies.

With that said, there is a case to be made for tax cuts generally, especially in high-taxed Europe. Lower taxes leave households and private businesses with more of their own, well-earned money; when people can keep more of the fruits of their labor, they can build that very self-determination that is such an integral element of conservative policy. Furthermore, high taxes contribute heavily to the uncompetitive economic climate in Europe.

Needless to say, I therefore strongly support any efforts to lower taxes across the continent, but only if the cuts are done correctly from the start. This article, in two parts, is aimed at straightening out the arguments for lower taxes in Europe.

Since the Swedish government took a bold step in its budget for 2025 and proposed a modest reduction in income taxes, I was excited to see what exactly they proposed. My disappointment over their measures is not based on substance—tax cuts are good—but on form. However, instead of belaboring the same points (see my article on the Swedish tax cuts), let me move on to outline how tax cuts should be executed to fulfill their intended purpose.

Let us begin with a simple theoretical framework, built on the so-called Laffer Curve. It is very often referred to as evidence that any cuts in income taxes are good cuts, and it does have some substantive merit. Economist Art Laffer was right about the basic theory behind his curve, a theory that is elegantly presented by Dan Mitchell of the Center for Freedom and Prosperity in this excellent video.

Unfortunately, Mitchell does not cover the shortcomings of the curve. Those shortcomings originate in the fact that when Laffer developed his theory for how tax cuts stimulate the economy, he failed to take into account three major variables that have subsequently proven to limit the power of Laffer’s supply-side tax cuts. These omitted variables are important enough to weaken—and even nullify—the positive effects that Art Laffer predicts will come from his recommended supply-side tax cuts.

The first variable to drain the Laffer Curve of power is price stability. In his book The Great Deformation (Public Affairs, 2013), David Stockman, former Congressman and head of the White House Office of Management and Budget, explains how Art Laffer’s proposal for tax cuts to the Reagan administration would improve the federal budget if and only if America continued to suffer from the high inflation that plagued the country when Reagan took office.

Without going into the technicalities of Stockman’s criticism, the conditions that he referred to in his book no longer exist in the U.S. economy. Therefore, his critique of Laffer, while relevant at the time, is less of a concern today—but it should not be ruled out from any conversation about tax cuts, in America or in Europe.

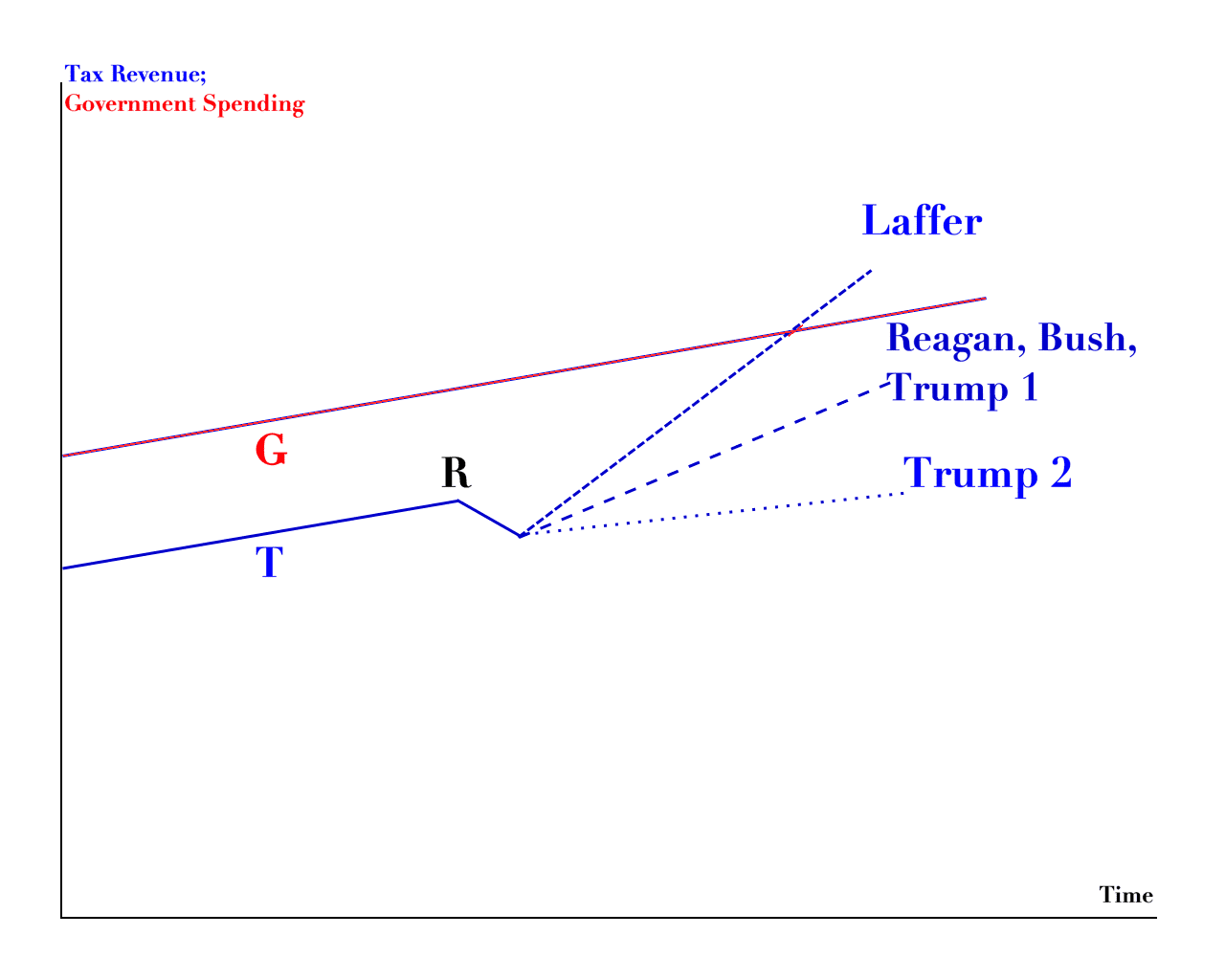

The second and third variables that limit the power of the Laffer Curve have to do with government spending. Let us use Figure 1 to illustrate the flaws with the Curve. Suppose a government’s spending increases along the purple line called G. Tax revenue, T, increases along the blue line, which initially rises largely on par with G. However, since tax revenue is less than government spending, at point R the legislature of this hypothetical country decides to take measures to close the budget gap. They zero in on a Laffer-style supply-side tax reform.

Initially, the lower tax rates reduce tax revenue collected, but when people respond to the lower rate by working more, ideally it causes a sharp rise in taxes paid. This is the Laffer scenario in Figure 1:

Figure 1

When taken from a doctrinaire standpoint, the Laffer curve predicts that supply-side tax cuts always pay for themselves as well as provide extra revenue to close the government budget gap. However, this is possible if and only if the supply-side tax cuts can grow future tax revenue so fast that they outpace the growth in government spending.

Back when Ronald Reagan was president and Congress passed a major tax reform designed in Art Laffer’s spirit, government spending still outpaced tax revenue. This does not mean the theory behind the tax cuts was wrong per se, but it does mean that the Laffer enthusiasts in the Reagan administration were significantly over-confident in just how much better the federal government’s finances would be when the tax cuts had worked their way through the U.S. economy.

President George W Bush spearheaded a similar tax reform soon after being elected in 2000. The fiscal result was similar to that from the Reagan tax reform: a healthy increase in tax revenue, but no balanced budget. Again, the architects behind the tax cuts failed to take the proper rate of spending growth into account; even though there was a noticeable rise in tax revenue after the cuts, they ultimately failed to catch up with federal spending.

The tax cuts during Donald Trump’s first term fell victim to similarly flawed fiscal forecasting. However, by the time Trump was elected in 2016, another variable had eaten its way into the complexity of calculating the potential benefits of tax cuts: not only was government spending growing too fast for tax revenue to catch up, but the very size of government in the U.S. economy had now come close to the critical level of 40% of GDP.

When the government consumes four out of every ten dollars or euros of economic activity, its sheer size works as a suppressant of economic growth. I analyzed the relationship between government size and economic growth on pp. 72-75 in my book Industrial Poverty; briefly, it is a statistical fact that an economy loses at least one percentage point’s worth of inflation-adjusted GDP growth for every year that its government consumes at least 40% of GDP.

When Trump took office in January 2017, the economy was dancing on the edge of that 40% line; although temporarily exceeding it with a hefty margin during the 2020 pandemic, total government spending has remained a whisker below 40% of GDP even as the Biden administration has gone about its own spending spree.

However, if the U.S. economy slows down without corresponding moderation in government spending, we could easily pass that line at any given time. It would therefore be safe to assume that if Trump is elected to a second presidential term and decides to try another round of tax cuts, he would face the strongest resistance from the economy itself of any president with that very same ambition. Therefore, it is only fair to recommend to Trump that he—should he win in November—concentrate his economic reform efforts on the spending side before attempting any more tax reforms.

The second part of this article will discuss the practical aspects—call them ‘design features’—of a successful European tax reform.